Tiki Central / General Tiki

interesting tiki reads

Pages: 1 7 replies

|

K

Kailuageoff

Posted

posted

on

Wed, Sep 8, 2004 1:36 PM

While we are waiting for Ben to post/photocopy/or typeset and print his book about his grandfather, here's something else to read. I found this article from the Honolulu Weekly while looking for web content on our old buddy Donn Beach. If you've already seen this, ignore it. If not, enjoy. The Way We Were by Curt Sanburn December 20, 2000 In his salad days, Honolulu architect Pete Wimberly regularly wore a pair of Bermuda shorts, a short-sleeve shirt and sneakers without socks to his office. Once in the office, he would Scotch-tape cardboard over the air-conditioning vents, open the länai door and start sketching. o local materials: coral stone, lava rock, wood beams, thatch, bamboo, etc. – and glass; A prime example: The Waikikian Hotel (1956) was an unair-conditioned, two-story beachfront hotel on a very narrow lot with lush, tiki torch-lit gardens and a dramatic, hyperparabolic soaring lobby inspired by Melanesian men’s-house forms. |

|

K

Kailuageoff

Posted

posted

on

Wed, Sep 8, 2004 1:45 PM

Here's another article. This is about Paul Page. It was written back in 1997. I http://www.wfmu.org/LCD/18/ppage.html Or, you can just read this.. Paul Page by Domenic Priore It's pretty easy to see how time and adulation could pass by an old salty sea dog like Paul Page. Then there's the fringe musician who works for a living, playing at Polynesian-themed restaurants every night and maybe getting around to pressing up an album or so for their barroom clientele. One may even believe that nothing significant, relevant or “valid” could come from such recordings. After all, isn't the essence of a lounge repertoire nothing more than familiar covers, maybe given a perverse “entertainer” twist? I would have stumbled upon Paul Page even if I never read the REsearch books Incredibly Strange Music Vol. I & II. He certainly wasn't featured in those books. As a surfer, I'd been collecting Hawaiian and Exotica records casually for years. Look in the puny record collection of even the most jock-like surfer asshole, and he'll be sure to have something Hawaiian to remind him of “the islands.” On a recent trip to Honolulu I got extremely lucky. Froggie's Records, who for years had been selling used books and vinyl to the underground market, was finally closing its doors, and I scooped up about 50 albums for a buck apiece. Knowing I couldn't take everything home, I only bought locally pressed items that never make it to the mainland, let alone thrift shops. I had to be selective. I picked out what seemed to be the purest or most ethnic stuff: LPs with Hula maidens swaying next to gourds and palm trees. LPs with the most predictable wacky Hawaiian settings on the cover that contained the raw deal inside. As soon as I pawed past the clearly unusual cover of Pieces of Eight (I was trying not to buy records by white guys - haoles if you will), something stopped me, and I had to go back. Here's some haole cat who looks like Gary Cooper wearing a Skipper hat on the cover of an album with a pirate-like title. What the hell is he doing here? I turn the cover over and ponder these sketches of docks, seagulls, ships, barnacles, islands, tikis...STOP RIGHT THERE - TIKIS? Noticing the name of the steel guitar player as Hawaiian, I figure what the hell, this must be worth a buck. I boxed my purchases and mailed `em back to the mainland, mystified and wondering what the hell that was all about? Of course, in a stack of 50 LPs ( and 50 78's procured in the basement of an old lady's house it was my good fortune to raid), this was definitely the first thing I had to check out. I pretty much knew what the rest would sound like, the individual favorites would come later. Who the hell was this Polynesian Pirate guy? That had to be answered. On first spin, it became clear that this was a winner. A cheap-sounding Chinese gong blasted a tinny, echoless introduction to “China Nights,” which apparently had been a good place for Page's backing group, The Island-Aires to “live and love.” So it's the decadence of the wandering seaman we're dealing with already. Next up, it's as flipped as it's ever gonna get, as we are introduced to Paul Page...narrating “When Sam Comes Back to Samoa.” (Can this guy actually sing, or is this just a put on?): Now Sam's been gone for a long, long time while he's been away Rock `n Roll has come & gone and Jazz is here to stay! When Sam goes back to Samoa He'll have to change all his wicky-wacky-wu* (hardly actual Samoan language, friends) for to Swing and Sway, the Island Way means Rock-A-Hula baby, I love you Rock-A-Hula honey, I love you It's pretty clear from this statement that the album came out sometime after the release of the Elvis Presley film “Blue Hawaii” and before February 7, 1964. Page comes off like a gracious host on the entire LP. The Island-Aires sing a few genius numbers (“Ports O' Call,” “Matey” and the peppy “Let's Have a Luau”), Bernie Kaii Lewis plays some splendid steel guitar solos on “Beyond the Reef” and “Sweet Someone,” and Page lays down some fine benedictions himself. Most of the tunes included are originals, and some lines, perhaps, only Page can sing in his own inimitable style: It doesn't cost a cent for her upkeep for there's nothing that she needs! All she wears is a great big smile and a little string of beads (“My Fiji Island Queen”) Then there's the big emotional number, “Castaway.” Backed by Bernie Kaii Lewis' sad steel guitar, a despondent Page slowly repeats “Castaway. Castaway. Castaway. Castaway..” in such a reflective tone that it's obvious he's adrift, and a dreamlike states takes hold: Once I had my love beside me in a harbor called home and now without my love to guide me I'm just a derelict on the foam The album ends with the “Pacific Farewell Medley” representing New Zealand's Maori (“Now Is The Hour”), The Philippines (“Philippine Farewell”), Japan (“Sayanara”), Tahiti (“E Maururu A Vaai) and Hawaii (“Aloha Oe”). Over Bernie's steel guitar, Page recites a descriptive Don Blanding poem called “Aloha Oe” that echoes this most famous melody of the islands. You're swept away, the masterpiece is in the bag, and you wonder “where is this guy, and what the hell is he doing now?” I caught up with Paul Page through ASCAP, whose logo is proudly emblazoned on the back cover of every Paul Page album I've seen. In fact, one of the oddball things about Page's liner notes is the way he boasts about his membership in the song publishing organization. He's 85 years old now, and the rough life of a seafaring beachcomber has caught up with him. His hearing is almost gone, and in the past two years it's been getting tough for him to remember all the details of his illustrious, exotic career. Once a male model who auditioned for a part against a young John Wayne, Page now fittingly wears an eye patch. The ravages of hard drinking and wild women in various ports have taken their toll. The guy in Old Spice commercial plays a role; Paul Page lived it and wrote songs to tell the tale. “I was quite a rounder in my day...there's too much to tell. I was busy modeling for photographers and working on radio. I knew so many women in my modeling days, I must've gone to bed with over 400 women. Isn't that awful? Terrible...and I never once every had any kind of disease. I'm clean.” Page was reared in Indiana, and by the time he was in high school became “the youngest commercial newspaper editor in the United States” he brags. “Walter Winchell once called me the multiple man, because I had so many amazing talents...at least a dozen of With this wisdom and encouragement from an American folk hero of such magnitude, Page took his Alaskan experience and brought it back home to nearby Chicago. “I always liked Hawaiian music. It was during these radio broadcasts that Page began to incorporate the element of Polynesian poetry. He was especially inspired by Don Blanding, the “Poet Laureate” of Hawaii whose 1928 book “Vagabond's House” featured the verse of a drifting beachcomber and cameo-styled illustrations of island scenery. Paul Page would soon adapt Blanding's art style to the exotica environment, but initially Page concentrated on Blanding's poetic dream world to conjure up a floor show atmosphere unique in its time (and non-existent today). When Page came in off the road, he developed modeling as a sideline income. “I was a very popular photographers model for magazines. About that time I auditioned for apart in a movie with John Wayne. He was the same size I was.” On the West Coast trip Page made contact with Sol Hoopi, the legendary lap steel guitarist reputed to have inspired both bottleneck/slide blues musicians and country artists in the development of the pedal steel guitar. Hoopi also headed up a booking agency in Hollywood - the industry relied on him to provide dark-skinned Hawaiians as extras in both the popular Polynesian films of the era, such as Bing Crosby's Waikiki Wedding, and in Westerns, where the kanakas and wahines came in handy as Native Americans. Hoopi's connections eventually lured Paul Page to Los Angeles. “I worked at The Seven Seas in Hollywood with Sol Hoopi, the nightclub across from Grauman's Chinese Theater. I played Hammond organ and MC'd the floor shows with Lulu Mansfield.” The Seven Seas was indeed a glamorous night spot during the glory days of Hollywood's Dream Factory era. L.A.'s proximity to the Hawaiian Islands made the city a Mecca for the Hawaiian music craze of the 1920's, and clubs like The Hula Hutt, The Singapore Spa, Hawaiian Village and Hawaiian Paradise sprang up to accommodate the action. Even Clifton's Cafeteria downtown became a neon-tropic-art-deco paradise. Paul Page eased into this scenario in the early 1940s: “I moved my radio program to the NBC studios at Sunset and Vine, and then I'd go over and do The Seven Seas. I had my fun at the nightclub...that was my job as an entertainer.” When asked what he did on his day off, his answer was simple enough: “Slept.” At the advent of the television era in 1949, Page hosted the very first Polynesian T.V. show, which was an extension of his radio show and his floor show at The Seven Seas. “I had the Starr sisters in my band, a vocal trio. Kay Starr was one of `em. She became famous on her own, and I had five hula gals in my big band. Five Hula gals and three caucasian sisters. They were all good.” However, an accident soon forced Page off the air for a while, and he had to start all over when he got well. In the meantime, the exotica craze began to kick in hard in the Los Angeles area. Don the Beachcomber's became the hip Hollywood haunt where Clark Gable and his pals hung out. Martin Denny was playing in the bar while proprietor Donn Beach was busy inventing the Mai Tai and a slew of now-famous tropical drinks. Trader Vic's became San Francisco's answer to the reverie, and The Luau in Beverly Hills became a swanky alternative for the posh set. Tiki became the God of Recreation as soldiers continued to return to the Port of Los Angeles at San Pedro. James Michener's South Pacific was a Broadway smash, and Thor Heyerdah's adventure book Kon Tiki set the tone of Los Angeles during the Truman era. Soon the area was overwhelmed with tiki apartment complexes, a surfing craze and knock-off tiki restaurants by the dozens. Paul Page had little trouble finding work. “I played at a restaurant called `Pago Pago' off and on for 10 years. A columnist in Van Nuys said I was the most popular entertainer in the San Fernando Valley...that's a big valley, you know.” Coincidentally, one of Page's best tunes was titled “Pago Pago,” kicking off a personal trend wherein Paul Page songs (and LP's) would be named after tiki restaurants in the Greater Los Angeles area. Page worked at the “Pieces of Eight” in Marina Del Rey and sure enough, a great tune and an entire LP bore that name. Then there was the “Castaway” in Glendale, which was another great song and LP title. Finally, there was the “Ports of Call” in San Pedro, and of course Page did not miss the opportunity to name a cool song after this establishment, and follow it up with an LP bearing the moniker. “Down there, south of Los Angeles, I used to have an office right near the Port of Los Angeles. That album sold well in San Pedro...” Sheesh! Page went so far as to use the actual logos of these restaurants on the album covers. Exploitation of the best kind, indeed. While all this was happening, Page began to pursue his art career as well. “I sold some paintings for $4,000 to $5,000 and had a couple of art exhibits. One was at the Hollywood Musicians Union and another one was at Barker Brothers department store in Los Angeles. Don Blanding introduced me to the public...I loved him, and he loved me. He used to come in and see me all the time when I played at the Roosevelt Hotel in Hollywood. I did an album of his poetry after he passed away called `I Remember Blanding.'” Blanding provided Page with inspiration on the canvas and in verse, and this album was really over the top. Bernie Kaii Lewis provided ethereal steel guitar backdrop to Page's loving narration of Blanding's best work, and in turn the LP holds up as an intense artistic departure for Page as well; it's his Pet Sounds, his “Gates of Eden,” it's the Forever Changes of the Paul Page catalog. Keep in mind that Paul Page was pretty much making a living off a Los Angeles trend in the restaurant business. He'd make a nightly wage as a performer, a few dollars off of the D.I.Y. albums he was producing, and some dough perhaps from a modeling gig here and there. To bring in extra cash, Page indulged in two areas that can now be seen as extremely hip and ahead of their time. “I wrote songs for amateur songwriters in Hollywood for a song shark company. They'd send in their lyrics, and I'd write the music and record `e (the songs). Magazine ads, you know, for songwriters.” Hmmmnnnn...Paul Page also shared two vocations with recent phenomenon Harvey Sid Fisher: modeling and astrology songs. Some three decades before the unintentional novelty success of the bewildered Harvey Sid, Paul Page released 12 45RPM singles, years before any hippie astrology trend. One side featured an astrological analysis, and the flip had a song representing the month. He set up a separate record label for these ditties called, you guessed it, Astrology Records. Page was beginning to turn out albums at a consistent rate too, and the quality never suffered. He used the best talent around, which is odd for such independent releases, but Page certainly had the respect of the Hawaiian music community. “I worked with Jerry Byrd. He's the greatest steel guitarist in the business. Bernie Kaii Lewis was actually the greatest of them all, but he died too soon. He was good, I recorded with him a lot. He could play anything...he did 'Nova' on solo steel guitar - imagine that? You could play it on piano, but nobody could play it on steel guitar - it's too difficult. He could, though. I know all those Hawaiians; used to speak the language. Dick McIntire, Lani McIntire, Ray Kinney Alfred Apaka...all of `em. Even Harry Owens.” Paul Page sounded like none of them. What he accomplished in these individualistic recordings was unique. Completely based in a Hawaiian sound, his songs end up sounding like Polynesian sea shanties, with spoken word dramatics coloring the dynamic mix. By the time Page was making records, Martin Denny had become popular with “Quiet Village,” so in turn, Paul Page included an insane, diffused combination of tropical sound effects. He didn't bother to have his musicians shout out bird calls in time with the music, however. On his masterful Hawaiian Honeymoon album, the sound effects are somewhat arbitrarily laid on. They don't match the rhythm of the songs, but after repeated listening you get accustomed to what is initially scary stuff. One especially chilling moment, is the chant tune “Au-we Wahine,” where the jungle drums clash with the teeth of some god-forsaken jungle animal that I won't attempt to identify. Then there's his “Big Island concept album” called The Big Island Says Aloha, where Page has deftly chosen all tunes featuring references to Big Island locales. It's true genius to sit back and revel in tunes like “Akaka Falls,” “Hilo March,” “Chicken Kona Kaii” and “Little Grass Shack in Kealakelua, Hawaii.” By this time, Page had made his exit from Los Angeles to the island of Hawaii. “I played the Kona Coast, and was the best known entertainer on the Big Island. I worked for the Kona Steak House and I wrote for the Kona Hilton Hotel. I played all over the islands, and knew Martin Denny well. I'd been out to his house many times in Honolulu, and he used to come and see me when I played.” Paul Page became so firmly entrenched in the culture that he became the president of the Hawaiian Professional Songwriters Society. For their newspaper, he penned a cartoon column as “Chief Wahanui.” His love for the music had consumed his being. On his first LP recorded in Hawaii (Passport to Paradise) Page even showed a social consciousness in his lyrics: Across the water see how they rise concrete to the skies Tall tiki towers reminding me, Hawaii's on the go and this I know Au E Mau Ke Ea O Kaina I Kapono just as true as in kamehameha's day and the blue island sky will reflect in the water if we all try to keep it that way (“Ala Wai Blues”) He'd definitely flipped - big time. So firmly entrenched in the home of his first love, Passport to Paradise includes perhaps the greatest tribute to Hawaiian music ever recorded, “The Big Luau in the Sky.” When I brought this song up, it didn't take long for the withered memory of Paul Page to strike up the words off the top of this head. “Oh yeah, that was one of my favorites. There's a narrated verse where I mention practically every important Hawaiian musician of this century - you name WFMU Homepage | LCD Contents page | Hear Our Signal© 1997 WFMU. |

|

K

Kanaka

Posted

posted

on

Wed, Sep 8, 2004 2:33 PM

Great reads Kailuageoff. I love this kind of literature and history. Thanks for posting! Kanaka |

|

TC

Tiki Chris

Posted

posted

on

Wed, Sep 8, 2004 2:47 PM

Thank you so much, kailuageoff! that Pete Wimberly article is great! i'm a big fan of his style but i didn't know he was so prolific! take care, |

|

K

Kawentzmann

Posted

posted

on

Thu, Sep 9, 2004 5:17 AM

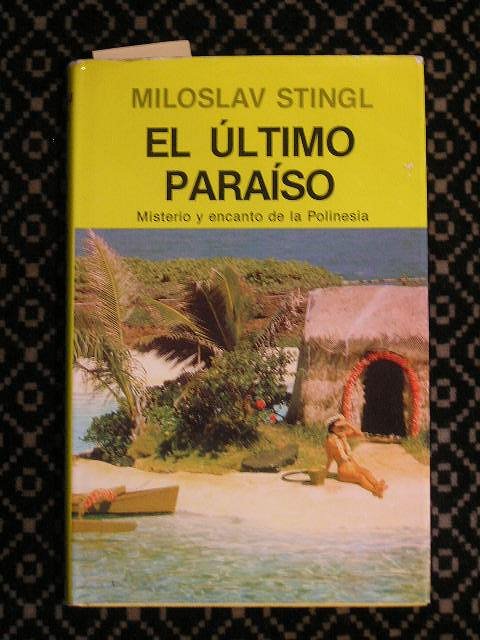

I have this box of four books, unfortunately for most TCers it’s printed in german, and I have no idea if there’s an english edition somewhere on the planet. Miroslav Stingl Book 1 Book 2 Book 3 Book 4 Stingl wrote this in the mid eighties. He is a czech ethnograph who’s travelled the world a lot, apparently focusing on the americas and the south pacific. In all books he refers to travels as far back as the late sixties, but the main travel writing is about his latest mid eighties travel through all of polynesia, micronesia and melanesia. It was really an entertaining read, even though I didn’t choose the order the author planned for the reader. I left the melanesian and micronesian books for last, but they were just as fascinating as the Easter Island/Tahiti/Newzealand and Hawaii chapters I enjoyed first. KK |

|

B

bongofury

Posted

posted

on

Sat, Sep 11, 2004 9:19 AM

Thanks Kailuageoff! Lotsa good info. Would still like to know what movie he was in with Lon Chaney Jr. |

|

Z

Zeta

Posted

posted

on

Mon, Feb 23, 2009 10:26 AM

[ Edited by: Zeta 2009-02-23 10:28 ] |

|

O

OceaOtica

Posted

posted

on

Mon, Mar 2, 2009 4:07 PM

"I have this box of four books, unfortunately for most TCers it’s printed in german, and I have no idea if there’s an english edition somewhere on the planet. " |

Pages: 1 7 replies