Tiki Central / Locating Tiki / The Kahiki, Columbus, OH (restaurant )

Post #700501 by Johnny Dollar on Tue, Nov 26, 2013 7:20 AM

|

JD

Johnny Dollar

Posted

posted

on

Tue, Nov 26, 2013 7:20 AM

the national archives graciously provided me with PDFs of the 1997 National Register for Historic Places Registration Form. a very interesting read. i took the liberty of processing the PDF into postable images and OCR text. please to peruse and enjoy :D

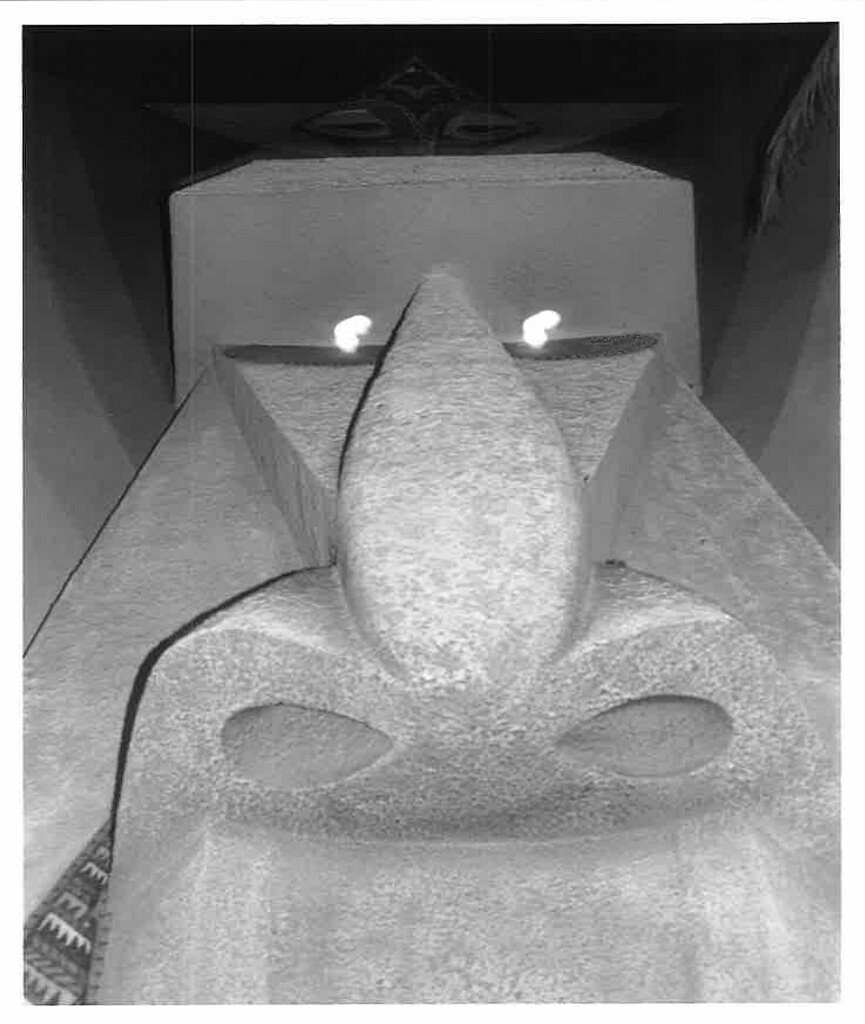

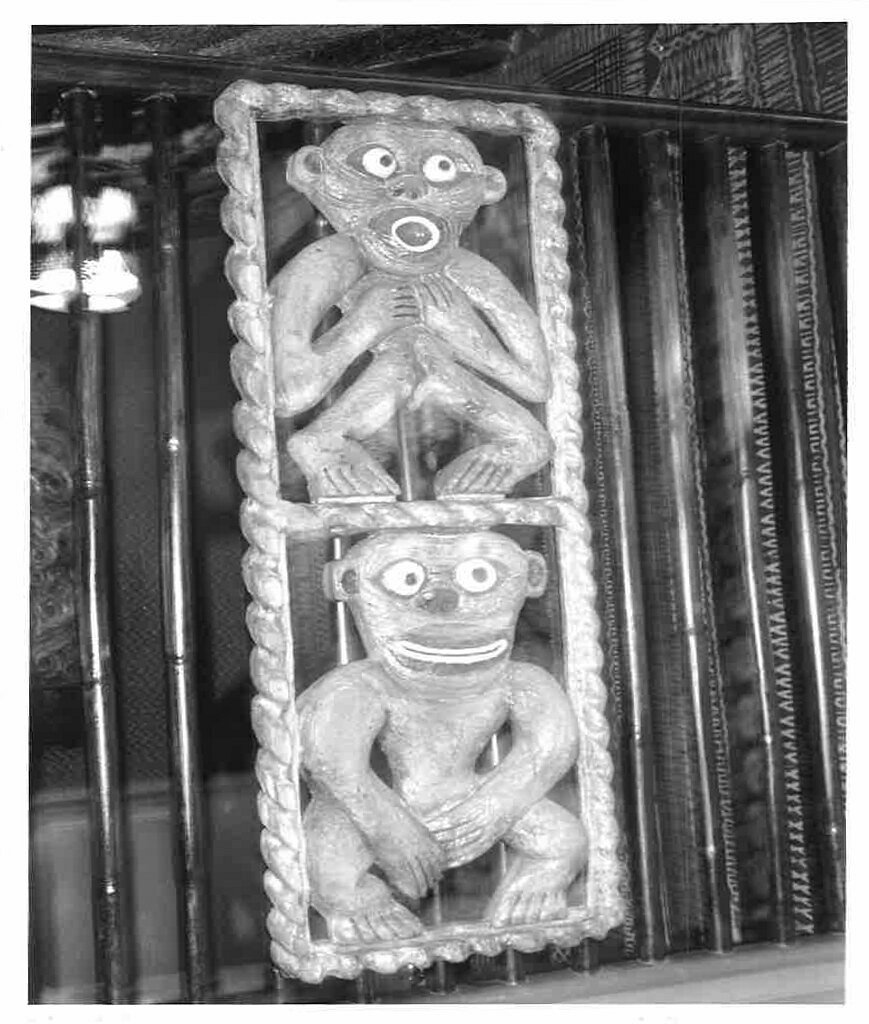

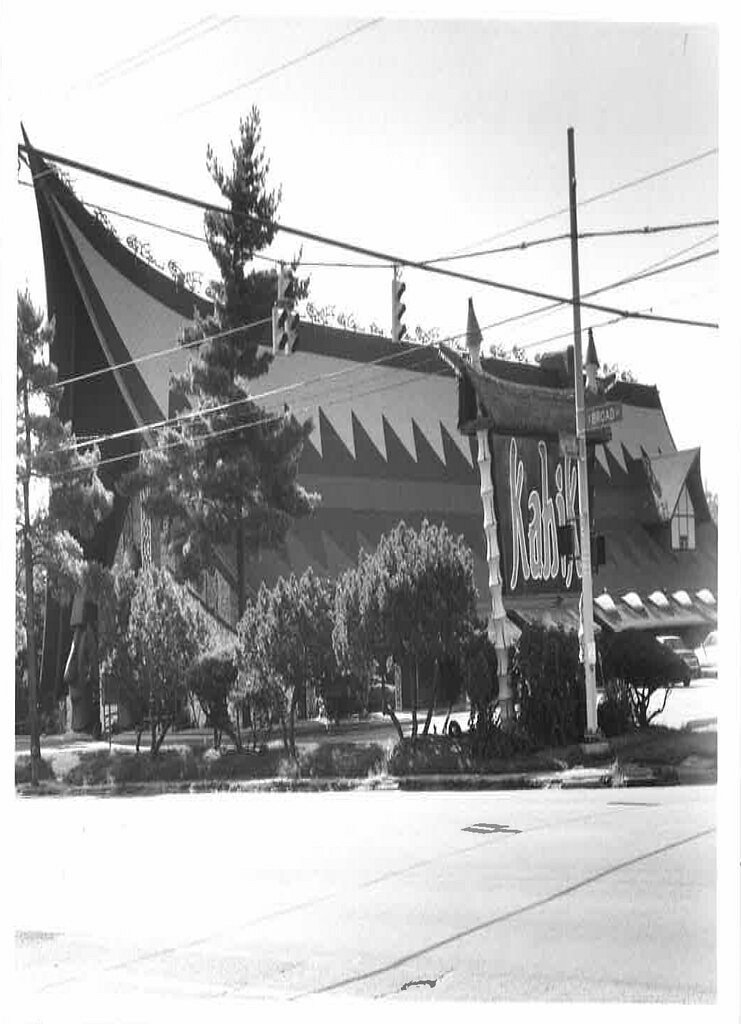

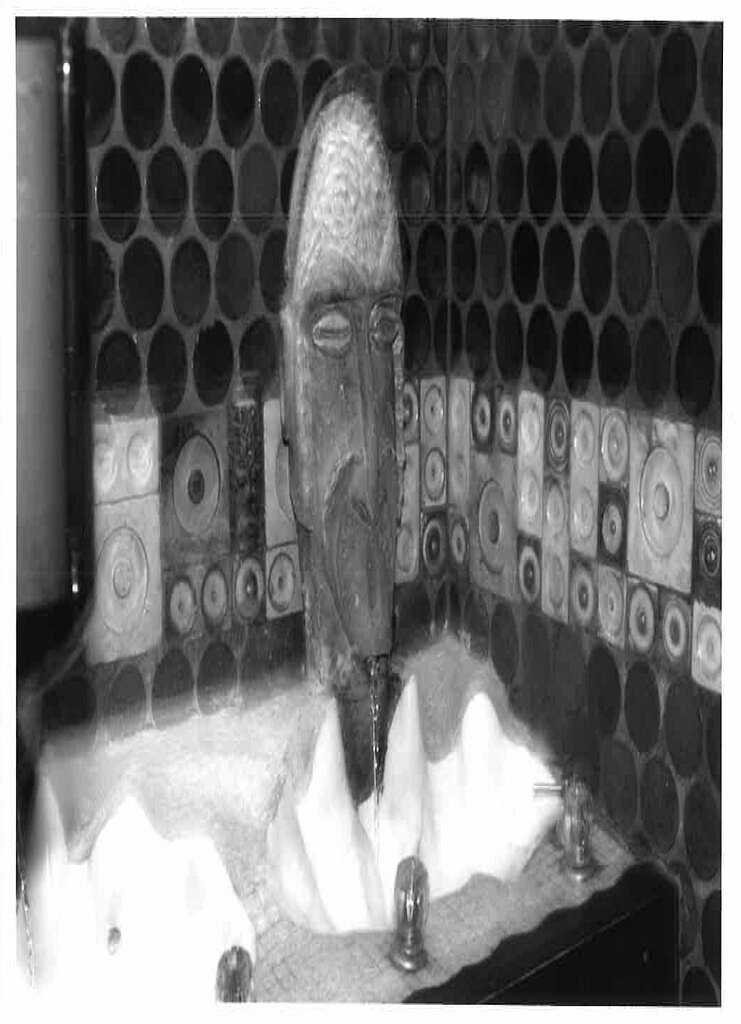

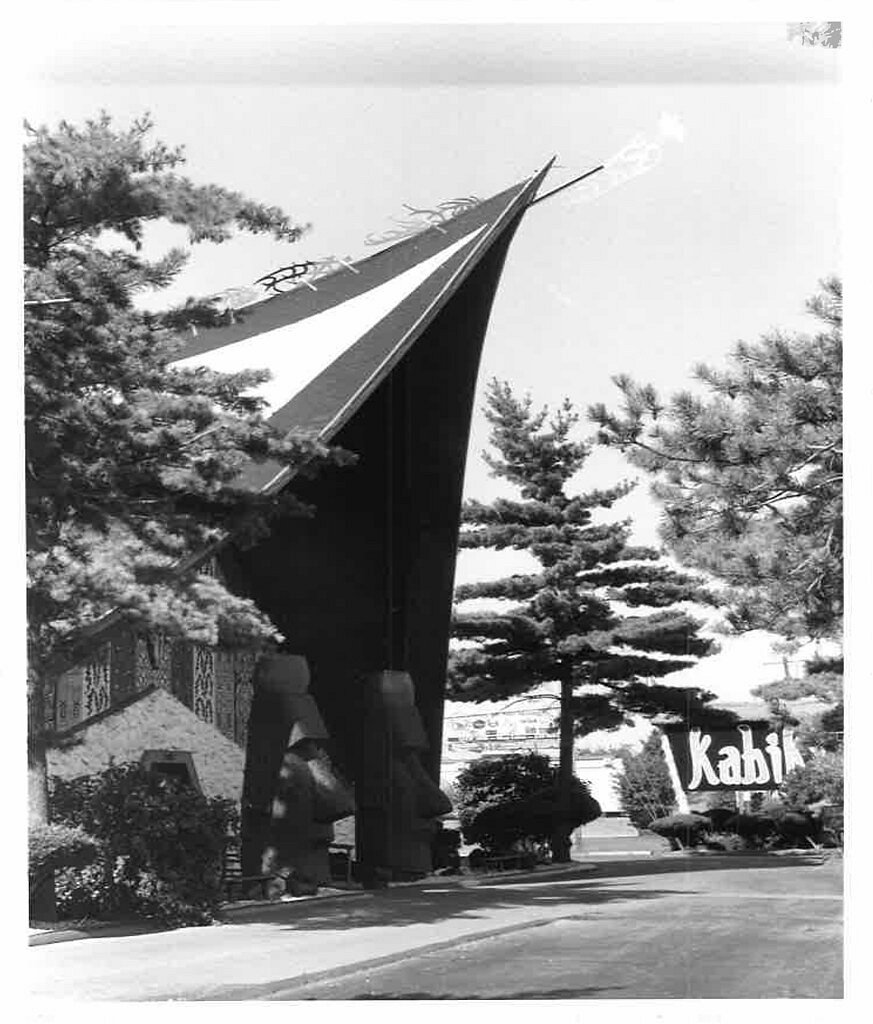

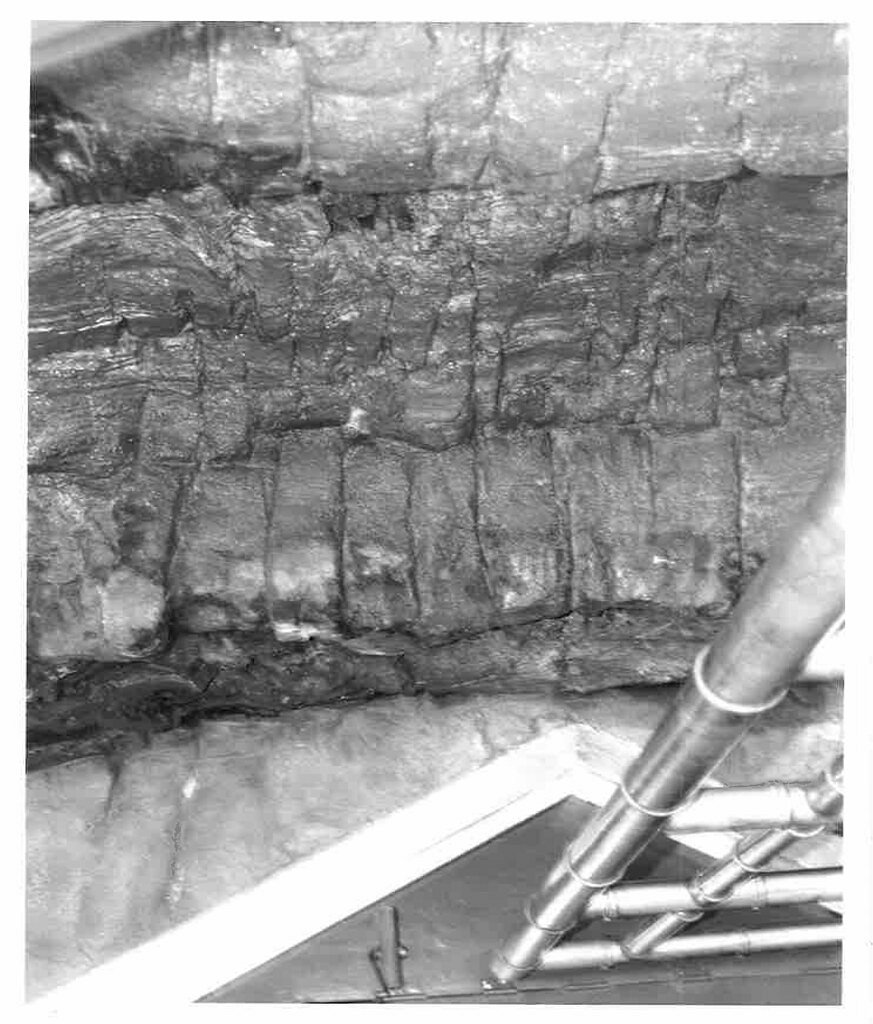

NARRATIVE DESCRIPTION The Kahiki is a large A-frame building located on a busy street in a suburban area east of downtown Columbus. It is situated on a comer lot with retail and fast food businesses on either side of it and across the street. (photos 1, 4) A driveway connects a small parking lot on the west side of the building to a much larger parking lot on the east side of the building. The Kahiki is visible from several blocks away and is a dominant presence along the busy corridor. The most striking feature of the structure is the immense roof. (photos 2, 3) Swooping down on both sides in a gently curved gable-shape, the roof is generally referred to as resembling a ship or war canoe. The roof is covered with individually cut asphalt shingles arranged in a red, white and black geometric pattern. Abstract fish designs are perched atop the ridgeline, while "a pelican sits at the tip of this imaginary boat, symbolizing plentiful food and good luck." (The World of Kahiki, p.l) (photo 9) The roof beams are supported on the long sides by short columns which are carved and painted with tiki figures. A large dormer is located near the roof line on the western facade. (photo 2) The rear facade provides entrance to the kitchen and is unadorned. The triangular-shaped front facade is decorated with colorful vertical panels of paintings. The bright colors of the paintings are juxtaposed against the cool white of the coral stone below it. (photos 12, 13) The Kahiki grounds are considered a contributing site working in tandem with the main building. (refer to site plan, p. 6) It enhances the dramatic architecture of the building and helps to invoke the exotic atmosphere created by the restaurant. The parking areas of the Kahiki are heavily landscaped which softens the effect of the open parking space around the building. Much of the vegetation is concentrated along Broad Street offering a buffer between the traffic and the building, although the building is clearly visible from the road. (photos 1,4, 5, 7) Two-foot high patio lights line the length of the driveway and illuminate the passage at night. Standing at the northwest comer of the lot is the original sign, which matches the architectural character of the building. The sign posts resemble large bamboo shoots while the lettering spelling out "kahiki" is a similar red as on the roof. At night the red letters glow with inviting warmth. (photos 1, 7, 44) Two other signs are present along Broad Street. A vertically oriented sign announces the driveway entrance and a smaller sign near it advertises a daily lunch buffet. (photo 3) Other directional signs are present along the driveway. All of the signs have similar "oriental" type print. A large tiki head sculpture resides in the grassy lawn facing Broad Street. A smaller sculpture nestled among the trees near the front of the building has red glowing eyes at night. (photo 8) A small building at the end of the main driveway entrance is designed in the same manner as the Kahiki itself. It houses electrical equipment and is being counted as a contributing building. (photo 42) A concrete block building with a mansard type roof is at the back of the lot, situated at the southeast corner of the Kahiki. (photo 43) The two buildings are not connected. This building houses the food preparation area for the wholesale distribution segment of the business. It postdates the period of significance and, therefore, is non-contributing. Although it is of later construction and is not of the same detail as the main building, it does not detract from the overall site. It is considerably smaller in scale than the main building and is painted with the same red color along with having the same fish design on the rooftop as the Kahiki. Its presence is largely obscured from the street by the landscaping. (photo 8) Two replicas of Easter Island carved heads flank the walkway into the entrance. (photos 10, 11) The black heads are 20 feet high and constructed of concrete. At night fire spews from the top of the heads. Immediately past the heads is a short footbridge with gold handrails that spans a narrow moat in front of the building. The bridge extends through the hexagon-shaped front doors. (photo 12) The first interior space just inside the entry doors is a small dark vestibule lit by blacklight. Water drips down the concrete cave-like walls into an interior pool. (photo 14) The quiet vestibule serves as a transitional space that instantly makes the guest forget that they just came from a typical busy suburban shopping area. (refer to floorplan sketch for interior description, p. 5) An interior door in the same shape as the exterior entry door lies at the end of the approximately six foot long vestibule. The wooden door surrounds are gold as well with decorative bamboo in between the actual door and the surrounds. Both the interior and exterior doors feature either painted or sculpted tiki figures on the handles. Once through the vestibule doors the space opens up into a circular foyer that is a representation of a grass hut. In the center of the foyer is a large hollow tiki mask fountain. (photos 15, 16) Its color and texture (resembling lava rock) is the same as the Easter Island heads. Water bubbles from the top of its head to the inside and then spills out its mouth into a circular basin. Periodically the fountain is engulfed in fog further adding to its intriguing presence. To the right of the door is an office, coat room and gift shop. A fountain rests between the gift shop and entrance to the Outrigger Bar. To the left of the bar entry is a hexagon-shaped doorway with the repeated gold color of the two previous doors. This doorway leads into the dining area and is on a direct axis with the vestibule and exterior doors. Another fountain is located to the left of the door and extends beyond the grass hut wall into the restaurant. A display area separates the fountain and the doorway leading to the restrooms, phones and banquet room. The floor is beige tiles in the shape of stones. The same floor material covers the vestibule bridge. The wall is decorated with painted tortoise shells and talles, "a shield-like affair placed at the entrance of island homes to ward off evil spirits." (Columbus Sunday Dispatch, p. 1) A small outrigger canoe hangs from the ceiling of the hut directly over the fountain. Ten hanging lights of differing designs encircle the canoe. The conical shaped ceiling is supported by bamboo beams with smaller bamboo cross supports and covered with thatch. (photo 35) The dining space of the Kahiki is so complex with ornament that it almost defies description. It is comprised of four dining huts of various sizes, rows of booths along the exterior walls, and a central open seating area at the opposite end of the room from the doorway. The concept of the design for the dining area is that of a traditional village of grass huts. On the wall opposite the foyer doorway is an 80 foot high tiki goddess with red glowing eyes and a functioning fireplace in its mouth. (photos 25, 26, 27) The fireplace towers over a central dining area in the open space between two dining huts. The space is further enhanced by artificial 40 feet high palm trees lining the edge of the huts. This central space is meant to represent a street through the village. The first dining hut is irregular in shape and to the left of the entry. (photo 22) Next to it is a narrow oval shaped hut. (photo 23) Behind the oval hut is a large rectangular hut in the manner of a meeting house with a bird sculpture above the door. (photos 23,24) An identical, although smaller, hut is across the "street." (photos 19,21) All of the huts, with the exception of the small oval one, contain varying table arrangements. Smaller intimate tables are intermixed with larger family sized tables. The huts are partitioned so that each table setting seems private. Booth seating lines the exterior walls. The east wall features a row of built-in aquariums containing fish to entertain diners. (photo 28) The west wall features a row of windows that offer a view into a tropical rain forest. (photo 29) Live birds are in the forest and a thunderstorm complete with lightning flashes every 20-30 minutes. The skylights present on the west facade allow natural light into the forest. (photo 2) No space within the restaurant is left unadorned. Sculptures, paintings, artifacts, hanging lights, shells, bamboo, woven grass, and nautical items are a sampling of the decorative pieces that give the Kahiki its incomparable ambience. (photos 30-35) Even items as mundane as ashtrays were made to complement the decor. (photo 33) Most of the decoration was made in the 1950s replicating actual designs and artifacts. The atmosphere is enhanced with island music in the background and dim lighting. The enormous roof beams forming the A-frame are exposed. The dining area seems immense, due to the height of the ceiling (112 feet above the floor), and intimate at the same time, due to the cozy lighting and human scale of the huts. The Polynesian theme is carried throughout the building into the secondary spaces. The Outrigger Bar is inside an oval hut. (photos 17, 18) The bar itself is roughly oval shaped with shelves in the middle. Two large masks on the top shelf and nearly 40 hanging lights illuminate the bar. One fountain, several tiki figures, two large paintings, and two bird cages containing macaws decorate the Outrigger Bar. Three horizontal windows and two overhead doors provide views into the dining area from the bar. The restrooms are generally nautical in theme, although water pours out of tiki heads into giant clam shell sinks. (photo 38) Public phone booths are concealed behind bamboo screens. (photo 37) The basement level contains a banquet room for public rental (photo 40), restrooms and employee service areas. While the basement space is not as elaborate as the restaurant, the Polynesian motif is still present with tiki figures, black lava rocks and bamboo ornamentation. (photo 39) The kitchen and access to it are located behind the fireplace. The kitchen only comprises about a fourth of the rear of the building. Much of the food preparation takes place in a separate basement kitchen. Also hidden behind the immense fireplace stack is a staircase leading to management offices. An upstairs bar was in existence until the late 1970s when all of the upstairs was converted to offices and a central reception space. (photo 41) A small window looks out from the office area onto the dining area below. The Kahiki enjoys an exceptionally high degree of integrity. The original piano bar that once resided in the front of the dining village was removed in c. 1979 and replaced by a fountain. The Maui Bar that was once left of the piano bar was converted to dining space at that time, as well. These changes are extremely minor within the context of the overall design. They do not detract from the atmosphere that has enchanted diners for 36 years. The Kahiki maintains a timeless quality through its near pristine original appearance. Statement of Significance Built in 1960-61 and opening its doors for business in February, 1961, the Kahiki is a large and imposing structure. As Ohio's only Polynesian restaurant and a significant example of the once popular national restaurant trend and unique building type, the Kahiki is being nominated under criteria A and C, consideration G at the state level of significance. Exceptional importance can be applied to the Kahiki based on the rarity and fragility of the property type. Recognized as the largest and best preserved Polynesian restaurant in Ohio (and perhaps the country), the Kahiki represents a significant period in the development of the theme restaurant industry. Criterion A In order to understand the popularity of Polynesian restaurants in the 1950s and 60s a brief history of Hawaii needs to be examined. While Polynesia includes a broader geographical area in the Pacific Ocean than just Hawaii, the United State's relationship and fascination with the Hawaiian Islands is integral to the proliferation of the Polynesian restaurant boom. Polynesia is generally defined as a large triangular area with Hawaii as the northern most point. New Zealand is the southwestern boundary point and Easter Island is the eastern point. Included within this large area are the Samoan Islands, Tahiti, and the Society Islands. (Fig. 1) While several thousand miles of water separated the Polynesian islands, inhabitants braved the ocean in canoes to settle on the various islands. The English navigator, Captain Cook, is credited with the European discovery of the Hawaiian Islands in 1778. Naming them the Sandwich Islands for his friend, Lord of Sandwich, Cook's discovery began a tradition of British exploration and trading in the Islands. The Americans soon followed suit with the first American vessel landing there in the winter of 1789-90. By the 1790s Hawaii was firmly established as a wintering stop in the China-Northwest American fur trade route. Its central location in the Pacific, the pleasant winter weather and the eagerness of the native chiefs to trade for Western goods made the Hawaiian Islands a perfect winter port. During its pre-contact history and throughout the early European trading years the islands were independent of each other with their own ruling kings and chiefs. A warrior from the island of Hawaii changed this destiny forever by uniting the eight islands known today as the state of Hawaii. Beginning in 1796 Kamehameha waged a ten year campaign that resulted in the islands' unification and his rulership of them. Under his rule, and his successors, trading with foreign interests continued simultaneously with the struggle to maintain independence as a nation. As early as 1816 a Hawaiian flag was adopted that combined the red and white stripes of America's and the Union Jack of Great Britain's respective flags symbolizing the importance of both countries to Hawaii's existence as a fledgling new nation. The United States-Hawaiian relationship continued to evolve as New England supplied the first missionaries to arrive in Hawaii in 1820. American trade increased with the demand for sandalwood and the emerging industry of whaling in the North Pacific also in the 1820s. In an effort to maintain independence from foreign intervention, especially the United States-Great Britain rivalry, Hawaii adopted its first constitution in 1840. The 1840s and 50s brought a series of treaties between Hawaii and England, France, and the United States. Despite the efforts toward independence, support for annexation to the States increased among residents in Hawaii. In 1853 the highest number of foreign residents in Hawaii were American. (Kuykendall, p. 84) The recent gold rush in California and the subsequent statehood status of California and Oregon increased Hawaii's export trade to America, which further strengthened its ties to the country. 1893 brought a revolution, largely supported by U.S. residents in Hawaii, to the island nation resulting in the overthrow of Queen Liliuokalani, the last monarch to rule the islands. The new Provisional Government succeeded in obtaining annexation to the U.S. in 1898 and territorial status two years later. As with earlier territories on the mainland that status was meant to serve as a transitional step into statehood. Although Americans had had an increasing presence in Hawaii since the first trading vessel landed there in 1789, the relationship was cemented with the territorial designation. At this time Hawaii began to gain military significance as the western most point of defense for the country. Large portions of land, primarily on the island of Oahu, were set aside for military use. Perhaps the most defining moment in the relationship between the United States and its island territory was the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The December 7, 1941 air strike prompted the entry of the United States into World War II and made the Hawaiian Islands a tangible part of the country to most people. Hawaiian delegates pursued statehood in earnest following the end of the war. After a scare of communism on the islands was put to rest and a series of complicated Congressional debates on the issue of Hawaii's potential statehood throughout the 1950s, it was finally made the 50th state in 1959. Polynesian restaurants were symbolic of a national fascination with Hawaii and its Polynesian heritage that originated in the late 1800s and culminated in the 1950s and 60s. Several factors contributed to this island attraction. The first obvious contributing factor was the geography and climate of the islands. The Hawaiian Islands were not only warm as with much of the southern United States, but they were remote and exotic as well. It was a paradise of lush green vegetation and brilliant flowers, mountains, beaches with warm ocean water, rainbows and gentle ocean breezes. Though the islands were a far away land not connected to the continental United States, they became much more accessible on May 1, 1947 when the first tourist-catered flight to Honolulu was completed by United Airlines. The veterans of World War II who had done duty in Hawaii and the South Pacific contributed greatly to the interest in Polynesian culture. The returning veterans brought home a taste for new foods and perhaps a sense of nostalgia for the beautiful islands where they had been stationed. "By the end of World War II many Americans had developed a genuine interest in the South Seas, and many more were looking for imaginative food as a relief from wartime austerity." (Stem, American Gourmet, p. 54) The emerging Polynesian restaurants were a way of sharing with their families the exotic island atmosphere that they had experienced. The movies of the 1950s and 60s can be viewed as a contributor to the fascination with Polynesian culture as well. Going to the movies had been a popular activity in the pre-war period and continued to be afterwards despite the increased competition from television. War movies were a popular genre for Hollywood producers. Numerous films featuring World War II themes were made in the late 1940s and 1950s. Many of these films took place in the South Pacific, which served to keep the memory of the tropical paradise fresh in the minds of war veterans. The 1950s also brought an equal number of war films about the Korean conflict. A distinct difference has been noted in the tone between the World War II and Korean War films. United States involvement in the Korean War was complicated in comparison to the simplified black and white issues of World War II. In discussing the World War II film, From Here to Eternity, author David Brode concludes that the film "suggested the growing strain of nostalgia America was just beginning to experience for the war years." (Brode, p. 99) Other 1950s war films are noted as projecting this sense of nostalgia that certainly was not lost on veterans. Other types of movies popularized the Hawaiian setting. One of Elvis Presley's best known movies, Blue Hawaii, was released in 1961. Presley starred in a second Hawaiian movie, Paradise-Hawaiian Style, released in 1966. The successful musical South Pacific was made in 1958. With the Korean Conflict, the Cold War, and the beginnings of the civil rights movement the 1950s were becoming increasingly more complex. "With such serious concerns, people needed to relax-and they had more leisure time to do it in, as well as more money to spend, than ever before." (Brode, p. 17) It is no surprise that a society living in fear of the bomb would look to the most idyllic part of the United States as a source of relaxation and escape. Modern flight had facilitated the accessibility of visiting Hawaii, although the expense of it was likely beyond the means of the average American citizen. They had to experience the islands vicariously through movies and other forms of entertainment, while those who had been able to make the journey sought to relive the vacation memories at home on the mainland. By 1959, the year of Hawaii's statehood, Polynesia was an everyday part of the popular culture and "all of America had the fever. Thor Heyerdahl's Kon Tiki had been a bestseller in 1951, South Pacific was everyone's favorite movie in 1958, James Michener's best-selling Hawaii also appeared in the late Fifties as did America's biggest fad, the hula hoop." Lovegren, p. 277) Michener was a veteran of World War II and had served in the South Pacific. Polynesian influence was seen in other places as well. The television detective series, "Hawaiian Eye", aired from 1959-1963. Luaus were promoted in cookbooks and magazines as diverse as House Beautiful magazine in 1950 to Sunset magazine in 1959 and the 1961 "Let's Have a Patio Luau" recipe pamphlet by Stitzel-Weller distillery of Kentucky (Stern, Encyclopedia of Bad Taste, p. 251). Luaus were the ultimate in party entertaining and "by the late fifties nearly every middle-class American suburban home with a patio had become the site of unsophisticated luaus." (Stern, American Gourmet, p. 56) The late fifties and early sixties surfing sub-culture celebrated beach life in California, but had its origins in Hawaii. Surfing is an ancient Hawaiian sport that had reached a fervor of popularity in California by mid-century. It was not long until the west coast fad had spread throughout the country. Songs with Hawaiian themes such as the Shadows' "Kon Tiki" and the Beach Boys "Luau" contributed to the overall surfing/beach culture. The Beach Boys used the Hawaiian Aloha shirt as part of their image. Naturally, the heightened interest in Polynesia in the fifties and sixties gave rise to the popular Polynesian restaurant fad. The years following WWII saw an increase in the restaurant business as a whole. American families began to eat outside of their homes in increasing numbers. Diner owners worked to reestablish their image from food for the male working class to a place for respectable families to dine out. With the efforts of the diner proprietors and other new establishments, the restaurant business began a marketing campaign aimed at the family. Dining out had become a treat for the whole family and a source of entertainment, as well as quality time away from the house. Restaurant owners quickly sought to capitalize on the entertainment value of dining out as evidenced by such novelties as car hops and supper clubs. Supper clubs in large urban cities had existed since the 1920s, but following the end of Prohibition in the 1930s they enjoyed even greater popularity. They offered diners both food and entertainment. Live bands provided music for dancing and some establislunents featured floor shows. An over the top glitzy atmosphere was also a large part of the overall supper club package. Often the atmosphere was created by using exotic or foreign themes. Polynesian restaurants easily fit into the supper club category of restaurants. They sought to transport the dining guests away from reality to a distant tropical island free of worries. An atmosphere of enchantment was created. The food was exotic in comparison to other restaurants. It arrived on fire or billowing with smoke, created by dry ice. Entertainment was provided by a live band or a floor show featuring hula and sword dancers. In essence Polynesian restaurants were more than eating establishments, they were places of entertainment where customers could spend a few leisurely hours. Supper clubs, especially the variety found in large cities, tended to appeal to an adult crowd, often an elite or socially stratified one. However, many Polynesian restaurants appealed to the whole family by offering special non-alcoholic versions of their powerful drinks for children and providing entertainment more suitable for family viewing. The roots of Polynesian restaurants can be traced to the 1920s. The Congo Room in New York City is noted for featuring hula dancers during that time. Magazines and cookbooks highlighted Hawaiian food both authentic and pseudo, much in the same way that they would promote luaus 30 years later. Don the Beachcombers in Hollywood is credited as being the first Polynesian themed restaurant, established in the 1930s. The restaurant featured Hawaiian food on the menu, potent alcoholic drinks (the Zombie was created there) and tropical decorations. Victor Bergeron, later known as Trader Vic, inspired by his 1937 visit to Don the Beachcombers founded the concept of Polynesian restaurants as they are known today. Following his visit he reorganized his Oakland, California bar, Hinky Dink's, reopening it as Trader Vic's in 1938. "He tore down the old deer horns and moose heads and covered the walls with green, grassy fabric and bamboo. 11 (Stem, The Encyclopedia of Bad Taste, p. 250) He created an exuberant South Seas atmosphere and expanded upon Don the Beachcomber's mind numbing drink menu, including invention of the Mai Tai. He traveled to Cuba, Florida, and Polynesia looking for new drink and food ideas, as well as additional artifacts for Trader Vic's. In the end he settled on Chinese food with pineapple, coconut and bananas added to give a "Polynesian" flare. His opinion was that Americans would not like real Polynesian food, therefore, he compromised with food that would be considered exotic, but not too foreign. Trader Vic's Polynesian concept met with great success. He followed his original restaurant with others, creating the Trader Vic's chain. By the 1950s Trader Vic's were located around the world. The restaurants were typically contained within Hilton and Weston hotels. Just as Victor Bergeron was inspired by Don the Beachcombers, others were inspired by him. Many independent restauranteurs opened Polynesian establishments. "Polynesian restaurants-which usually meant restaurants that served the same sort of food and drink as Trader Vic' s-opened by the score around the country." (Lovegren, p. 279) A second, smaller chain of Polynesian restaurants was founded by Steven Crane Associates in the late 1950s. Crane purchased the name Kon Tiki from author Thor Heyerdahl and used it for his restaurants. He also made use of Trader Vic's strategy of linking the restaurants with hotels, forming a partnership with the Sheraton chain. He had establishments in Montreal, Cleveland (now demolished), and Portland, Oregon. The Portland location received the most recognition because it directly rivaled Trader Vic's restaurant in that city. As with most trends, Polynesian restaurants began to lose their glamour and popUlarity. Dining tastes shifted by the late sixties and Polynesian restaurants began to be viewed as kitsch and not the sophisticated dining experience that they once were associated with. Many have closed throughout the country in places like Philadelphia, Atlanta, New York, and California. "Now, it seems, they are dying out, disappearing like thatched huts in a hurricane .... Trader Vic's the General Motors of Polynesian restaurants, has six locations left in the United States, down from a peak of nineteen in the early '70s." (Richman, p. 114) Even the ones located in Hawaii itself, where one would expect a heavy tourist trade to keep the concept alive, have gone out of business. The Kahiki falls into the broad context of the Polynesian supper club trend established by Trader Vic. He set the standard by which later Polynesian restaurants would be built. A major difference between Trader Vic's chain and independently owned Polynesian restaurants was that Trader Vic's tended to be inside larger hotel buildings, \vhereas independent ones typically were freestanding individual buildings. The Kahiki \vas built during the height of the Polynesian rage. It debuted as one of Columbus' premier supper clubs smoothly fitting into the dining and entertainment offerings of the city. During the construction phase Bill Sapp, one of the Kahiki owners, was quoted in the local paper as saying that "the Kahiki will be the largest Polynesian restaurant in the world and the first one of its type in Ohio." (Columbus Dispatch, 8114/60, p. 26A) The Kahiki was the bold dream of Bill Sapp and Lee Henry. Sapp and Henry had previously owned a bar, The Grass Shack, near the Kahiki location. The small bar had a Polynesian theme and was a popular destination for reminiscing WWII veterans in the 1950s. Sapp and Henry also owned an upscale restaurant, The Top Steak House, during that time and in the same vicinity. After the Grass Shack was destroyed by fire, they decided to continue with the Polynesian theme. Perhaps owing to their experience with The Top, they opted to build a supper club rather than simply replacing the lost bar. Sapp and Henry created Columbus' newest exotic supper club by painstakingly attending to every detail in the design and decoration of the building. Beginning in 1957 they began researching the possibilities for their new endeavor. They travelled extensively with their interior designer, Coburn Morgan, throughout the South Pacific in search of ideas and artifacts for the restaurant. They, along with the architects, also visited numerous Polynesian restaurants around the United States. "Throughout their travels, Sapp and Henry failed to find one which wasn't successful." (Tabor, p. 1) Design Associates of Columbus was chosen as the architectural firm with Ralph Sounik and Ned Eller being the principal architects. Groundbreaking for the site was in July 1960 with the grand opening occurring in February 1961. Sapp and Henry's dedication to the grand scale and elaborate theme of the Kahiki was rewarded immediately by the residents of Columbus. liThe doors opened in February, but gained such popularity that people would wait for hours in the cold just for the opportunity to venture into this strange new cultural environment." (Kahiki newsletter) Throughout the sixties the Kahiki was featured in several national food service publications, such as American Restaurant Magazine and Institutions. An advertisement in a 1967 Life Magazine issue proclaimed it "The World's Most Elaborate Polynesian Supper Club." (Life Magazine, page unknown) In 1978 Sapp and Henry sold the Kahiki to Mitch Boich. He brought Michael Tsao, the current president of the restaurant, into partnership that year. Eventually, in 1993 it was decided to incorporate the business. Shares in the Kahiki are now traded and it is run by a board of directors and the president of the corporation. In more recent years the business has expanded to include the manufacture of prepared food items with the Kahiki name and logo for distribution to state institutions and grocery stores. In order to meet the increasing demand for this segment of the business a food processing plant was constructed at the rear of the Kahiki site in 1995. Locally, it is important to note that the Kahiki is the last of the supper club restaurants left from that era. The Jai Lai, Columbus' only other remaining supper club, was sold this year and is currently undergoing conversion into a sports bar. Columbus has a significant restaurant history, including the world headquarters for several chains, both fast food and theme restaurants. The Kahiki is an important local representation of an era in entertainment and dining that has largely disappeared from the city. The word kahiki means "sail to Tahiti" and that is what the restaurant accomplishes. It is an imaginary journey to the islands of Polynesia. In 36 years the aim to symbolically transport and entertain guests has not changed. The piano bar was removed, but a live band plays Hawaiian music on weekends and the gong still sounds when someone orders the mystery drink. Fire still roars in the mouth of the dominating tiki goddess, thunderstorms cleanse the tropical rainforest, and many of the drinks and food dishes still arrive aflame or billowing with smoke. The Kahiki is significant as an excellent and remarkably intact example of the Polynesian restaurant building type. The Kahiki is a conglomeration of different architectural traditions from varying Polynesian island cultures, as well as, the neighboring island cultures of Micronesia and Melanesia. The form of the building is modelled after the young men's houses of the Yap Islands (fig. 2) and the men's ceremonial houses of New Guinea (fig. 3). The other major architectural feature of the Kahiki is the dining huts. They are based on the modest grass huts of Hawaiian villages (fig. 4). The interior ornamentation is derived from the artifacts of the South Seas, including nautical items that reflect the ocean existence of the various islands. A certain level of decorative elements had to be present in order to carry the diner's imagination to the South Seas. Tiki statues, shells, glass fishing weights, fountains, and aquariums were always used for creating atmosphere. The Kahiki designers took these pre-requisites seriously, employing an abundance of the decorative items. Combining them with other design features the Kahiki truly does transport dining guests to a magical island paradise. "If you are in the mood for an entertaining evening as well as good food, the Kahiki is one of the true showplaces of Central Ohio ... .If you haven't been to the Kahiki lately, you owe it to yourself." (Pigging Out in Columbus, p. 109) In comparison to the Trader Vic's restaurants and other Polynesian establishments, the Kahiki is perhaps more authentic in copying traditional Polynesian architectural forms. The Mai-Kai in Ft. Lauderdale and the Tahitian Lanai in Waikiki, Hawaii, now demolished, (fig. 5) are two of the more elaborate examples of the building type, like the Kahiki. Both Michael Tsao, Kahiki president, and Ned Eller, Kahiki architect, cite the Mai-Kai as being the only other Polynesian restaurant in the country that is similar in form to the Kahiki. The rest are additions to traditional buildings, even the soaring roofline of the Tahitian Lanai was an addition to the Waikikian Hotel. The architects and the interior designer, Coburn Morgan, were masterful in carrying out the grand vision of the Kahiki builders. Morgan, especially, had a strong voice in the creation of the restaurant. He completed the interior designs, much of the exterior, designs for the artifacts and fountains, as well as, recommending to the owners Design Associates as the architectural firm. Morgan designed other notable themed restaurants in Columbus such as the Jai Lai, the Sands Supper Club, and the Wine Cellar. He designed another legendary Ohio supper club, Tangier, in Akron. His commissions also included hotels and national restaurant chains, such as the original Bob Evans and Casa Lupita. The Design Associates firm was established in 1959 with Ralph Sounik and Ned Eller being two of the three partners. Incorporated in 1979 the firm today is known as S.E.M. Inc. They coordinated with Coburn Morgan again on the Sands Supper Club. The bulk of their commissions in the 1960s following the Kahiki project primarily included churches, schools, and houses. The Kahiki meets Criterion Consideration G because it is a significant representation of a form of entertainment and building type that was once popular at mid-century. It provides physical evidence of a larger societal enchantment with Hawaiian culture (often a perceived culture) and a reflection of Cold War escapism. Thirty to forty years have passed since the popularity of these restaurants were at their peak, thus allowing sufficient time to pass to examine their place in American culture. "Polynesian palaces were America's first theme restaurants. In as-much as these seem to be the future of the food-service business in this country, Polynesian restaurants may prove to be almost as important to our national heritage as the first automobile assembly line." (Richman, p. 114) Bibliography Blackburn, Mark, Hawaiiana: The Best of Hawaiian Design. Atglen, PA: Schiffer publishing Ltd., 1996. Brode, Douglas, The Films of the Fifties. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1976. Buck, Peter H., Arts and Crafts of Hawaii: Section II, Houses. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1964. Campbell, I.C., A History of the Pacific Islands. Berkely and Los Angeles: University of Cross, Robin, 2000 Movies: The 1950s. New York: Arlington House, 1989. Hibbard, Don and David Franzen, The View from Diamond Head: Royal Residence to Urban Resort. Honolulu: Editions Ltd., 1986. Hurley, Andrew, "From Hash House to Family Restaurant: The Transformation of the Diner and Post-World War II Consumer Culture," The Journal of American History, Vol. 83:4, March 1997, p. 1282-1308. Japikse, Carl, Pigging Out in Columbus: A Guide to the 111 Best Restaurants in Central Ohio. Columbus: Enthea Press, 1993. Judd, Walter F., Palaces and Forts of the Hawaiian Kingdom: From Thatch to American Florentine. Palo Alto, CA: Pacific Books Publishers, 1975. Kuykendall, Ralph S. and A. Grove Day, Hawaii: A History From Polynesian Kingdom to American State. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1961. Loffler, Ernst, Papua New Guinea. Victoria, Australia: Hutchinson, 1979. Lovegren, Sylvia, Fashionable Food: Seven Decades of Food Fads. New York: Macmillan, 1995. Mariani, John, America Eats Out. New York: William Morrow & Co., 1991. Marshall, John, "Kahiki," Columbus Monthly, January 1993, p. 84-86. Richman, Alan, "The Long Aloha", Gentlemen's Quarterly, March 1996, p. 112-118. Stern, Jane and Michael, American Gourmet. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1991. Stern, Jane and Michael, The Encyclopedia of Bad Taste. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1990. Stern, Jane and Michael, Sixties People. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1990. Tabor, Gail, Kahiki: A Polynesian Adventure, Columbus Sunday Dispatch, 9/24/61. Zmijewsky, Steven and Boris, Elvis: The films and career of Elvis Presley. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1976. Conversation with Ned Eller, Kahiki architect, August 13, 1997. Conversation with Ralph Sounik, Kahiki architect, September 24, 1997. Conversation with Michael Tsao, Kahiki President, April 18, 1997 and July 9, 1997. ________, Columbus Dispatch, 8/14/60, p. 26A. ________, Columbus Dispatch, 9/2/60, p. 26A. ________, Life Magazine, Advertisement, 12/1/67, page unknown. ________ , The World of Kahiki, Company Newsletter, 1995. Verbal Boundary Description The boundary of the Kahiki includes 1.66 acres. It is located in the Lincoln Park 2 subdivision of the City of Columbus; parcel numbers 089352, 089651, and 088460; lot numbers 6, 9-12. Boundary Justification The boundary chosen to include all property historically associated with the Kahiki site.

|