Beyond Tiki, Bilge, and Test / Beyond Tiki / Miami Beach Mid-Century Modern officially historic

Post #339427 by I dream of tiki on Fri, Oct 19, 2007 5:19 PM

|

IDOT

I dream of tiki

Posted

posted

on

Fri, Oct 19, 2007 5:19 PM

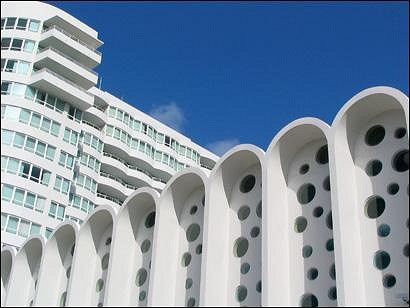

Miami Modern architecture recalls city's rise as glamour capital MIAMI -- What do the Fontainebleau Hotel, the Eden Roc Hotel, the Dezerland Hotel, and the Sheraton Bal Harbour have in common? Aside from being on Miami Beach, all were designed in the 1950s and '60s by the architect Morris Lapidus, and all are examples of an architectural style called Miami Modern, a.k.a. MiMo. The name MiMo (MY-moe) was coined in 1998 as a promotional term to build public support for preserving structures built after World War II through the mid-'60s. Overshadowed by the earlier and popular Art Deco, MiMo is now coming into its own. The postwar building boom in Miami coincided with its growing popularity as a glamour capital, attracting movie stars and entertainers such as Joan Crawford, Lena Horne, Anita Ekberg, Jackie Gleason, and the Rat Pack crew. Prosperity and glitz combined to produce an exuberant indigenous architectural style. At a time when most architects were embracing the Bauhaus ethic of ''less is more" to produce rectilinear forms in glass, steel, and concrete, architects in Miami, perhaps influenced by the sultry climate and vibrant light, were putting an exotic twist on the modernist aesthetic with curved surfaces, bright colors, concrete cantilevers, and circular holes in walls, like slabs of cement Swiss cheese. In addition to Lapidus, architects including Norman M. Giller, Igor B. Polevitzky, Melvin Grossman, and Kenneth Triester designed residences, hotels, motels, and commercial buildings in many parts of the city. "MiMo is not just a style, it's an umbrella term that encompasses several styles," says Randall C. Robinson Jr., the executive director of the North Beach Development Corporation and coauthor, along with Eric P. Nash, of ''MiMo: Miami Modern Revealed" (Chronicle, $40). MiMo includes subtropical modern, Frank Lloyd Wright-influenced cantilevers, the big Miami resorts, iconic monuments, and small apartment buildings. In addition to great photos, the book contains a glossary to summarize the style: A is for asymmetry, B is for boomerangs, C is for concrete canopies, etc. ''People ask me if I have a favorite building, and I don't," says Robinson. ''What's special is we have so many neighborhoods with examples of this architecture." One area rich in MiMo architecture is North Miami Beach, from 63d Street to 87th Terrace. Robinson's nonprofit corporation offers a walking tour of about 20 buildings on Fridays during the winter tourism season, and maps if you want to go on your own. Not to be missed are the turban-clad genies in front of the Casablanca (Roy France, 1949), the Deauville (Grossman, 1957), where the Beatles performed in 1964 on ''The Ed Sullivan Show," and the Sherry Frontenac (Henry Hohauser, 1947). The most flamboyant of the group, Lapidus, a Russian emigre, was reviled by critics and adored by the public for his over-the-top attitude. In his mind, Lapidus was designing not just buildings but places to live out fantasies. His hotel lobbies were like luxurious movie sets, with massive chandeliers, circular ceilings, and dramatic staircases. You can visit two of his biggest developments, the curvaceous Fontainebleau Hotel (1954) and its next-door neighbor, the Eden Roc Resort (1956), which are 20 blocks south of the North Beach tour. (Most hotels back then were designed with the automobile in mind, so it helps to have a car to get from one MiMo area to another. Fortunately, there's a public parking lot for the beach at 46th Street, from where it is an easy walk to both hotels, the lobbies of which were recently renovated to their original design.) In the Eden Roc, the feeling is elegant and subdued, with a carved Italian marble and mahogany reception desk and polished terrazzo floors. Photos of Sammy Davis Jr., Milton Berle, Jayne Mansfield (who honeymooned here), and other celebrities hint at the glamour of that era. The new renovations make one imagine that, if you wait long enough, Elizabeth Taylor or Dean Martin might appear at the bar. The Fontainebleau has a different feel. An open, airy space looks out to the ocean, with gigantic crystal and gold chandeliers overhead, and the famed ''stairway to nowhere" that floats up one wall. (The stairway led to a coat-check room where, after dropping off your wrap, you could make a grand entrance down to the lobby.) It's no wonder that this hotel was used for a scene in the 1964 James Bond movie ''Goldfinger." If you want to linger, both hotels have bars in the lobby, as well as restaurants with ocean views. The Fontainebleau's Bleau View is more on the formal dining side, while the Eden Roc's Aquatica is an outdoor beach bar and grill, with light dining options and a rum list with more than 30 choices. Another area where you can see MiMo architecture is along the Lincoln Road Mall in South Miami Beach, a pedestrian-friendly shopping concourse with Lapidus's cantilevered boomerang shapes offering shady areas to sit, funky fountains, and undulating concrete walls. At the ocean end of Lincoln Road, the Ritz-Carlton, South Beach, has renovated the former Lapidus-designed DiLido Hotel lobby to reflect the aesthetic of MiMo days, while updating stucco and plastic materials with wood and stainless steel. On the mainland, Biscayne Boulevard between 19th and 82d streets gives some smaller-scale yet equally playful examples of the MiMo style, such as the Vagabond Motel (Robert Swartburg, 1953) and the property at 5600 Biscayne, a former tire showroom now turned into a pizzeria/carwash (Robert Law Weed, 1960). If all this architectural exuberance seems like too much fun, keep in mind what Lapidus wrote in his 1996 autobiography, ''Too Much Is Never Enough" (Rizzoli): '' 'Less is more.' How stupid can you be. Less is not more. Less is nothing." Contact Necee Regis, a freelance writer in Boston and Miami Beach, at [email protected]. © Copyright 2007 Globe Newspaper Company. |