Beyond Tiki, Bilge, and Test / Beyond Tiki

Miami Beach Mid-Century Modern officially historic

Pages: 1 10 replies

|

IDOT

I dream of tiki

Posted

posted

on

Tue, Jun 19, 2007 1:51 PM

I just found out this information in a tourist magazine - of all places. The tourists know before the locals do. While its probably just a title for now (just as the Kahiki was historic), its still exciting that a potential new wave of preservation may occur like in the case of Art Deco. Enjoy. Mimo, or Miami Modern, Follows Miami Deco: Tours of Miami Beach's 50s and 60s architecture

Miami’s South Beach is synonymous with 20th century Art Deco architecture. The neighborhood’s tale of transformation taught the world that cities can prosper by preserving what’s funky and unique. But the Miami area is not just about Deco. After World War II, a new building style emerged, and that style, called MiMo (pronounced My-Mo), is now officially historic. In June of 2006, the city of Miami officially designated a MiMo/Biscayne Boulevard Historic District. The district, according to Florida’s Division of Historic Resources, contains more than 100 buildings from the 1950s era. And what is MiMo? Short for Miami Modern, it is a term coined by MiMo boosters Randall Robinson and Terri D’Amico to describe Miami’s wild, modern buildings that sport odd shapes, wild signs, extravagant porte-cocheres and bright colors. Hotels like the Deauville and Fontainebleu are the more famous of the genre; the style also appears in smaller doses in places like the Collins Avenue Publix, which sports an intricate mosaic in boomerang shapes. There are many variations. There is Resort MiMo, best seen at hotels like the Sherry Frontenac. Iconic Modernism shows off big arches, boomerangs and wild shapes. Subtropical Modernism encompasses Modernism with Florida touches like louvers and wide eaves. Wrightian Modern includes stone pylons and built-in planters. The district is definitely a work in progress; some of the buildings are not yet restored. Tours are Saturday, led by Robinson himself. And self-guided walking tours are made easier by a colorful map given out by North Beach Development. Maps are available at North Beach Development Corporation offices at 1181 71st Street, Miami Beach. 305-865-4147, gonorthbeach.com Article located at: http://www.visitflorida.com/cms/e/cms_2797.php [ Edited by: I dream of tiki 2007-07-03 18:54 ] |

|

I

ikitnrev

Posted

posted

on

Tue, Jun 19, 2007 4:08 PM

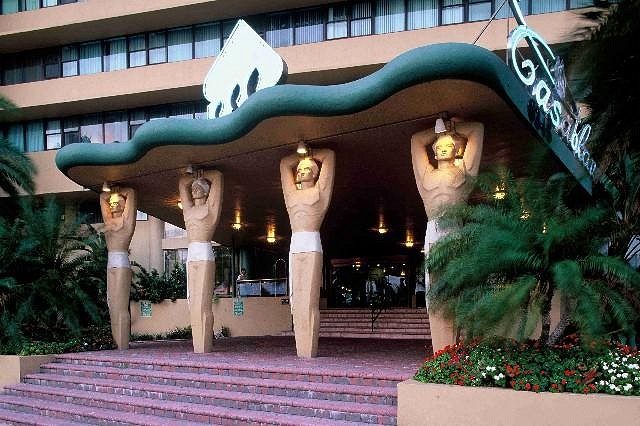

That is great news. I dream of Tiki took a few of us for a Hukilau Sunday afternoon tour of some of the Miami architecture, and it was a real treat to have a guide and driver who was so knowledgable on the roads and the various neighborhoods of the area. I will always appreciate Liz for pulling over to the side of the road (illegally?) so I could run back and take a few photos of those amazing Casablanca pillars. There appears to be a ton of new high rises being constructed in that area, so anything that can help preserve the older buildings will be helpful. Vern |

|

IDOT

I dream of tiki

Posted

posted

on

Sat, Sep 15, 2007 10:09 PM

During the last Hukilau, I ran into a number of people who remember various hotels from the Miami Mid Century Modern Style that have long since been torn down. I ran across a book with great photos of those same old hotels in Sunny Isles. Nice to know there is some documentation out there still for those us with nostalgia. Also some nice shots many spots all around Miami. MiMo: Miami Modern Revealed Great for the photography alone. |

|

IDOT

I dream of tiki

Posted

posted

on

Fri, Oct 19, 2007 5:15 PM

More wonderful articles. It seems Miami Beach is not the only ones getting the message. The City of Miami just declared BiBo - Biscayne Boulevard - commericial district as historic back in 2006. Here are some articles: HISTORIC RESOURCE OF THE MONTH: Officially designated by the City of Miami as a historic district in 2006, the Miami Modern (MiMo)/ Biscayne Boulevard (BiBo) is Miami's sole commercial historic district. The district's shining stars are the motels along this major thoroughfare: a distinctive group of architecturally and historically significant edifices illustrative of the 1950s hey-day of motor culture and the optimism and sense of prosperity that characterized the era. Notwithstanding, the MiMo / Biscayne Blvd. district is also home to some notable examples of other styles of historic Miami architecture, such as Art Deco, Streamline Moderne, and Mediterranean Revival. District boundaries: Biscayne Blvd., NE 50th St. to NE 77th St. To see and do in MiMo/Biscayne Blvd.: |

|

IDOT

I dream of tiki

Posted

posted

on

Fri, Oct 19, 2007 5:19 PM

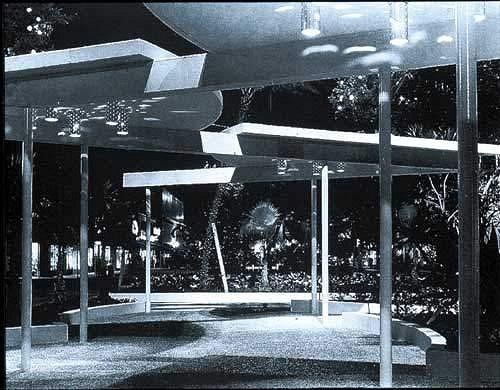

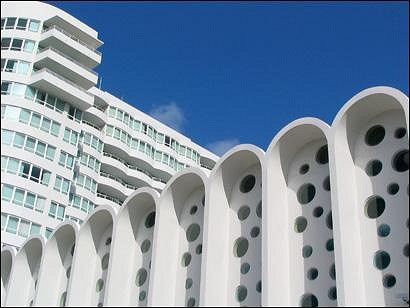

Miami Modern architecture recalls city's rise as glamour capital MIAMI -- What do the Fontainebleau Hotel, the Eden Roc Hotel, the Dezerland Hotel, and the Sheraton Bal Harbour have in common? Aside from being on Miami Beach, all were designed in the 1950s and '60s by the architect Morris Lapidus, and all are examples of an architectural style called Miami Modern, a.k.a. MiMo. The name MiMo (MY-moe) was coined in 1998 as a promotional term to build public support for preserving structures built after World War II through the mid-'60s. Overshadowed by the earlier and popular Art Deco, MiMo is now coming into its own. The postwar building boom in Miami coincided with its growing popularity as a glamour capital, attracting movie stars and entertainers such as Joan Crawford, Lena Horne, Anita Ekberg, Jackie Gleason, and the Rat Pack crew. Prosperity and glitz combined to produce an exuberant indigenous architectural style. At a time when most architects were embracing the Bauhaus ethic of ''less is more" to produce rectilinear forms in glass, steel, and concrete, architects in Miami, perhaps influenced by the sultry climate and vibrant light, were putting an exotic twist on the modernist aesthetic with curved surfaces, bright colors, concrete cantilevers, and circular holes in walls, like slabs of cement Swiss cheese. In addition to Lapidus, architects including Norman M. Giller, Igor B. Polevitzky, Melvin Grossman, and Kenneth Triester designed residences, hotels, motels, and commercial buildings in many parts of the city. "MiMo is not just a style, it's an umbrella term that encompasses several styles," says Randall C. Robinson Jr., the executive director of the North Beach Development Corporation and coauthor, along with Eric P. Nash, of ''MiMo: Miami Modern Revealed" (Chronicle, $40). MiMo includes subtropical modern, Frank Lloyd Wright-influenced cantilevers, the big Miami resorts, iconic monuments, and small apartment buildings. In addition to great photos, the book contains a glossary to summarize the style: A is for asymmetry, B is for boomerangs, C is for concrete canopies, etc. ''People ask me if I have a favorite building, and I don't," says Robinson. ''What's special is we have so many neighborhoods with examples of this architecture." One area rich in MiMo architecture is North Miami Beach, from 63d Street to 87th Terrace. Robinson's nonprofit corporation offers a walking tour of about 20 buildings on Fridays during the winter tourism season, and maps if you want to go on your own. Not to be missed are the turban-clad genies in front of the Casablanca (Roy France, 1949), the Deauville (Grossman, 1957), where the Beatles performed in 1964 on ''The Ed Sullivan Show," and the Sherry Frontenac (Henry Hohauser, 1947). The most flamboyant of the group, Lapidus, a Russian emigre, was reviled by critics and adored by the public for his over-the-top attitude. In his mind, Lapidus was designing not just buildings but places to live out fantasies. His hotel lobbies were like luxurious movie sets, with massive chandeliers, circular ceilings, and dramatic staircases. You can visit two of his biggest developments, the curvaceous Fontainebleau Hotel (1954) and its next-door neighbor, the Eden Roc Resort (1956), which are 20 blocks south of the North Beach tour. (Most hotels back then were designed with the automobile in mind, so it helps to have a car to get from one MiMo area to another. Fortunately, there's a public parking lot for the beach at 46th Street, from where it is an easy walk to both hotels, the lobbies of which were recently renovated to their original design.) In the Eden Roc, the feeling is elegant and subdued, with a carved Italian marble and mahogany reception desk and polished terrazzo floors. Photos of Sammy Davis Jr., Milton Berle, Jayne Mansfield (who honeymooned here), and other celebrities hint at the glamour of that era. The new renovations make one imagine that, if you wait long enough, Elizabeth Taylor or Dean Martin might appear at the bar. The Fontainebleau has a different feel. An open, airy space looks out to the ocean, with gigantic crystal and gold chandeliers overhead, and the famed ''stairway to nowhere" that floats up one wall. (The stairway led to a coat-check room where, after dropping off your wrap, you could make a grand entrance down to the lobby.) It's no wonder that this hotel was used for a scene in the 1964 James Bond movie ''Goldfinger." If you want to linger, both hotels have bars in the lobby, as well as restaurants with ocean views. The Fontainebleau's Bleau View is more on the formal dining side, while the Eden Roc's Aquatica is an outdoor beach bar and grill, with light dining options and a rum list with more than 30 choices. Another area where you can see MiMo architecture is along the Lincoln Road Mall in South Miami Beach, a pedestrian-friendly shopping concourse with Lapidus's cantilevered boomerang shapes offering shady areas to sit, funky fountains, and undulating concrete walls. At the ocean end of Lincoln Road, the Ritz-Carlton, South Beach, has renovated the former Lapidus-designed DiLido Hotel lobby to reflect the aesthetic of MiMo days, while updating stucco and plastic materials with wood and stainless steel. On the mainland, Biscayne Boulevard between 19th and 82d streets gives some smaller-scale yet equally playful examples of the MiMo style, such as the Vagabond Motel (Robert Swartburg, 1953) and the property at 5600 Biscayne, a former tire showroom now turned into a pizzeria/carwash (Robert Law Weed, 1960). If all this architectural exuberance seems like too much fun, keep in mind what Lapidus wrote in his 1996 autobiography, ''Too Much Is Never Enough" (Rizzoli): '' 'Less is more.' How stupid can you be. Less is not more. Less is nothing." Contact Necee Regis, a freelance writer in Boston and Miami Beach, at [email protected]. © Copyright 2007 Globe Newspaper Company. |

|

IDOT

I dream of tiki

Posted

posted

on

Fri, Oct 19, 2007 5:21 PM

From Preservation Online, the online magazine of New Historic District Showcases Miami's Modern Architecture On June 6, Miami's preservation board unanimously approved the creation of a historic district between NE 50th and 77th Streets, a commercial corridor on Biscayne Boulevard that showcases the architectural style known as Miami Modern, or MiMo. Now preservationists and planners have begun mapping out the restoration of the new district's decaying structures. "The district is an architectural treasure trove of 20th-century architecture predominated by motels from the 1950s," says Randall Robinson, a city planner and executive director of the North Beach Development Corp. "It is the first historic district of 1950s motels that we know of, but it also has lots of offices and pre-war Art Deco buildings." Robinson and interior designer Teri D'Amico coined the term MiMo to describe the city's mid-century modern architecture—an amalgam of various influences from Mediterranean revival to Art Deco. "We did it to capitalize on the success of [Miami's] Art Deco district," Robinson says. "We made sure it rhymed with the word 'Deco.'" The Art Deco district was added to the National Register in 1979 and is a prominent preservation success story. MiMo is an umbrella term for a set of styles, Robinson says. "Some of the features are unique to Miami, but many of them have universal symbols of established styles," he says. Unique features include the sun grilles and stonework depicting nautical themes. Nina Korman, a journalist and member of the Miami Modern Coalition, a local preservation group, says that restoration plans are in the preliminary stages. "Nearly every motel is going to need work, not to mention the office buildings and shops," she says. Most of the motels are still in use. Robinson says that the structures primarily require cosmetic rather than structural rehabilitation, focusing on details such as glass walls and neon signs. Although the city's government and preservation board have been supportive, Robinson says, property owners are wary. "There's the universal fear of historic preservation," he explains. "People have seen how successful the Art Deco district has been, but they still don't get it." Robinson says that the city should create tax incentives tailored to the district, as well as provide technical assistance on restoration, to encourage motel owners to stay put and participate in restoration work. Regardless of incentives, preservation doesn't happen overnight, he says; the Art Deco district took more than 10 years to become a cultural and economic powerhouse. Korman says that, as a resident, preserving the MiMo historic district is important to her. "It has been somewhat draining but ultimately extremely gratifying," she says, "knowing I'm helping to revitalize a piece of the city where I grew up." All Rights Reserved © Preservation Magazine | Contact us at: [email protected] |

|

IDOT

I dream of tiki

Posted

posted

on

Fri, Oct 19, 2007 5:36 PM

Biscayne Boulevard Historic District Miami Hopes to Protect Era of Architecture Along BiscaynePosted on Tuesday, March 07, 2006

A SoBe for MiMO? Preserving the Miami modern era could give Biscayne and Art Deco cache For years the Maule building sat forlornly on Biscayne Boulevard at 52nd Street, a hollow shell on borrowed time. Once the headquarters of the Ferre family enterprises, designed to show off the virtues of the family's product -- concrete -- it was considered by architecture experts to be one of the finest buildings of its kind. But in recent years, it was fenced off, its windows knocked out and trashed, its death warrant all but signed. Last week it succumbed to the wrecker. A wooden sign announces the condo tower to come in its place. Yet the 1954 Maule building could be the martyr that propels a new wave of historic preservation in the city. MiMo buildings reflect Miami's adoption of stripped-down, geometric modern design after World War II, an optimistic time when Miami was on the rise, the Rat Pack ran around town, and mass family tourism -- and thus the roadside motel -- was born. The forward-looking buildings feature gravity-defying concrete projections, sun screens made of metal grilles, fancifully shaped concrete blocks. The proposed district, scheduled to receive preliminary consideration from the city's Historic and Environmental Preservation Board today, would encompass both sides of the boulevard from 50th Street to the Little River just north of 77th Street.

LEGAL PROTECTIONS MiMo proponents, who followed the Maule building's march to extinction with consternation, are ecstatic. The district's creation, they say, could help inspire an urban revival to rival Miami Beach's. City preservation officer Kathleen Slesnick Kauffman said the boulevard -- which some have dubbed ''MiMo's Main Street'' -- has the potential to become a lively, walkable and architecturally unique district, Miami's version of Lincoln Road. "Miami is finally going to have its South Beach, with all the different styles in one place,'' said Randall Robinson, a planner and architectural historian. The proposed district caps a three-year effort to protect significant, endangered buildings that began under former preservation director Sarah Eaton, who retired last year. Bill Hopper, president of the Morningside Civic Association, applauded the plan, which he said should help preserve the historic scale of the strip, where condo proposals have drawn opposition from nearby residents. Preservation could, however, provoke opposition from property owners on the long-depressed boulevard who have pinned their hopes on high-rise condos and commercial redevelopment. It could also get a lukewarm reception from skeptics who dismiss MiMo architecture as schlock, the product of an era that built quickly and cheaply. The notion of designating modern buildings as historic has proven divisive even among preservationists, many of whom believe efforts should focus on saving older, traditional buildings. ''I'm sure there is going to be some opposition,'' said Otto Boudet-Murias, the city's chief of planning and economic development. ``But I haven't heard any complaints or any great anxiety yet.'' DEMOLITION NIXED Historic designation would not foreclose additions, renovations or redevelopment along the boulevard. But it would likely bar demolition of significant buildings, including most of the signature MiMo motels, many of which are run-down. All plans for renovations or redevelopment would be reviewed by the preservation board to ensure they respect the boulevard's historic character and low scale. ''It doesn't mean you can't develop it. That's a common misconception,'' Kauffman said. ``We want it developed.'' Doing that the right way, however, will require a strategy that fosters creative renovations and new uses for buildings, said Aristides Millas, an architecture historian and professor at the University of Miami. ''The boulevard has some really juicy buildings that scream at you to get your attention. They're fun buildings, not overly serious buildings,'' said Millas. ``But they're not in very good shape. These pieces of history are important if they can be woven into a coherent plan for the boulevard. The buildings have to have new uses that are economically viable. You can't just save concrete.'' YEARS IN THE MAKING Consideration of the district first arose almost three years ago, when the city hired a consultant to draw up a proposal. But the plan appeared dormant until earlier this year, when the city commission approved a condo project for the Maule building site. Eric Silverman, who is renovating the Vagabond motel, got a sympathetic hearing from commissioners, including Johnny Winton, whose district includes the boulevard, when he complained that other MiMo buildings might soon follow the Maule. Winton subsequently met with city planning officials to consider legal protections. The preservation office has been working on the plan for several weeks, but waited until notices of the proposal went out to property owners to go public, fearing it could provoke demolitions. The notices trigger a moratorium on demolitions and new building permits in the proposed district while the preservation board weighs the plan. A final vote could come in April. In considering the district, Miami is catching up to Miami Beach, which has already established historic districts that include numerous buildings from the 1950s. The Beach is also considering a district along Collins Avenue that would safeguard two of MiMo's crown jewels, architect Morris Lapidus' Fontainebleau and Eden Roc hotels. But many MiMo buildings have just begun reaching the 50-year mark that qualifies them for historic designation. ''It really defines Miami,'' said interior designer Teri D'Amico, who coined the tern ''MiMo.'' ``That was our Golden Age. It was a time when America shone and we were coming up with something unique.'' Copyright 2006 Knight Ridder MiMo Biscayne Association Phone 305-758-6144 Email: [ Edited by: I dream of tiki 2007-10-19 17:37 ] |

|

IDOT

I dream of tiki

Posted

posted

on

Tue, Jan 1, 2008 5:49 PM

"Make Way for/ MiMo"

In William Gibson’s 1980s cyberpunk classic “The Gernsbach Continuum,” the protagonist finds himself transported to an alternate reality created by nostalgia for the future that never was—the technotronic future of the Jetsons, where robots fold the laundry, the economy prospers, the children are safe, and the family hovercraft swoops past gleaming city infrastructures. By the 1980s, this romantic future had already proven itself an abortive dream emanating from a nostalgic past. But after WWII, in an era of prosperity and optimism since unparalleled, the dream was only beginning. Automobiles with soaring fins tacitly sliced through the air with graceful ease; sparkling new appliances promising to alleviate housework appeared in every kitchen. The combination of affordable automobiles, increased disposable income, and more leisure time proved irresistible, and Americans began to vacation as never before. Perhaps nowhere was the postwar craving for the futuristic more evident than on Miami Beach where, during the 1950s and 1960s, wildly inventive hotel designs emerged to satiate the requirements of the prosperous new middle-class on vacation. Resort area architects attempted to realize through their buildings what we of a more cynical age now concede to be science fiction. These architects created a unique futuristic look in Miami Beach that became known as Miami Modern—MiMO. The name MiMO was created two years ago by Randall Robinson, a planner with the Miami Beach Community Development Corporation, and Teri D’Amico, an interior designer and adjunct professor of hotel design at FIU, to refer to the hotel architecture of Greater Miami built between 1945-1969. The most famous architect of this style is Morris Lapidus, whose Fontainebleau, Eden Roc, Seacoast Towers, Deauville, and Di Lido, although typically considered Art Deco, are actually prime examples of MiMO. Naturally, the idea of MiMO did not spring up from the sea full-fledged; it has its roots in the Bauhaus movement of early 20th-century Germany, as propounded by architects and designers whose ideas soon made their way overseas: Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Marcel Breuer. Their conception was in its own way also nostalgically futuristic: they dreamed of streamlined, non-ornamental buildings that were comfortable, functional, and could be enjoyed by the working class, whose values, the Bauhaus school sentimentally believed, had not been corrupted by the overwrought aesthetic of the bourgeoisie. How wrong they were.

The pure Bauhaus vision failed in the United States on every level: working-class people certainly didn’t have the means to engage the services of a Bauhaus architect, and the booming middle-class was intent on showing off its money with as many flourishes as possible. After WW II, elite college campuses clamored for the Bauhaus style, known as Modern (Le Corbusier designed a building for Harvard, Breuer for Vassar), but elsewhere architects began adapting Modern to the prevailing mood of their clients. In Miami, this meant ornamentation galore, but in clean, geometric forms: Tropical Art Deco, a combination of streamlined moderne and the art deco of 1920s Paris. At first glance, it can be difficult to differentiate MiMO from Art Deco. “We fall into a little bit of a trap when we make these distinctions,” admits Robinson of the MBCDC. “Anything old and vaguely decorative is called Art Deco.” Although there seem to be many similarities, MiMO comes closer to Modern in its use of certain features like asymmetry; kidney-bean and oval shapes and curves; carports with angular, amoeba-like, or winged shapes; semi-circular driveways at the entrance rather than front porches; and brise-soleils (sun shades). Although South Beach is almost exclusively filled with examples of Art Deco, some MiMO buildings do exist: the Miami Beach Fire Station Number 1 (11th and Jefferson), the 1688 Meridian Building, The Penguin Hotel (1418 Ocean Drive), The Shore Club (1801 Sunset Harbor Drive), The Di Lido (155 Lincoln Road), and Burdines (17th and Meridian). For the most part, however, MiMO architecture tends to congregate in mid and North Beach, Sunny Isles Beach, and Bay Harbor Islands. One architect who bridged the Art Deco-MiMO gap was Albert Anis, who created such Art Deco South Beach landmarks as the Clevelander, the Savoy, the Leslie, the Waldorf Towers, the Avalon and the Winter Haven before he moved on to his equally dramatic yet more organically shaped MiMO hotels of mid-beach, the Royal York (5875 Collins Ave.) and the Bel-Aire (6515 Collins). Both hotels were recently the subjects of community protests against developers and calls for preservation, to date without success -- the Bel-Aire’s façade has already been destroyed. Although preservationists are fighting the good fight, they are hampered by three harsh realities: (1) the current building code allows for far taller buildings than are currently standing, which is a boon for developers (2) The National Register of Historic Places, which would need to certify MiMO buildings in order to protect them from the wrecking ball, is unlikely to list properties younger than 50 years old unless they show “exceptional significance,” and (3) MiMO architecture is not universally considered to be of “exceptional significance.”

Even MiMO architect Morris Lapidus has weighed in against preservation; he was quoted in The New York Times as saying of the Bel-Aire, “Try living in a hotel like that. They were nice hotels for their time, but that time has passed.” Architect Norman Giller, who designed The Carillon (6801 Collins Ave.), lamented to The Miami Herald, “I think something needs to be done. It’s a crime the way [The Carillon’s] just sitting there. It’s an eyesore.” This particular eyesore won a Hotel of the Year award in 1957 for its distinctive glass façade and accordion wall in the ballroom. More than 40 years later, it stands abandoned. Fortunately for Giller, Robinson, D’Amico, and other would-be MiMO saviors, Miami Beach has a history of vigorous design preservation, and many of its most staunch preservationists are also politicians. The fight to save Art Deco is still relatively fresh in the minds of many commission and city council members, and they are likely to look with a favorable eye on pleas to save the old MiMO façades. In the meantime, nostalgia for the future lives on in Miami Beach, where we have the good fortune to be living in our very own Gernsbach Continuum. Article posted on Miami Beach USA |

|

IDOT

I dream of tiki

Posted

posted

on

Tue, Jan 1, 2008 6:11 PM

Listing on Historic Preservation Miami Miami Modern (1945-1965)

The prosperity of post-World War II America is reflected in the inventive designs of the Miami Modern style. The Miami Modern style evolved from Art Deco and Streamline Moderne designs, reflecting greater modern functional simplicity. Although the style was used on various types of buildings, it is typified by futuristic-looking hotel and motels. Characteristics include the use of geometric patterns, kidney and oval shapes, curves, stylized sculpture, cast concrete decorative panels and stonework depicting marine and nautical themes, particularly at the entrances. Overhanging roof plates and projecting floor slabs with paired or clustered supporting pipe columns, as well as open-air verandas and symmetrical staircases are also typical design features. Examples: Vagabond Motel Vagabond Motel a. This classic “jet age” motel embodies the characteristics of the Miami Modern style, including an open-air plan, jalousie windows, geometric designs, overhanging roof lines, stone facing, and sculptural elements depicting marine life and other nautical themes. At the time of construction, B. Robert Swartburg was one of the most prominent and innovative architects in Miami-Dade County, creating such notable structures as the Miami Civic Center Complex, the Bass Museum, and the Delano Hotel.

b. Historic postcard of the Vagabond Motel, date unknown. |

|

IDOT

I dream of tiki

Posted

posted

on

Mon, Apr 14, 2008 12:00 AM

Morris Lapidus NOTE: This article is out of date because it still speaks of Morris Lapidus as still being alive. Lapidus of Luxury Morris Lapidus By Jonathan Ringen

Always a hit with the people, Miami's showman architect has finally wowed the critics, too. Morris Lapidus seems to have a favorite adjective: unusual. Use it, as he most often does, to modify the words shape, form, color, lighting, and adornment, and you get a pretty good summation of the delirious style practiced by the architect of Miami Beach's superglam midcentury Fontainebleau and Eden Roc hotels. "My whole concept of life is to make it more unusual, more interesting, more warm," says the architect who last November both celebrated his 98th birthday and was honored by the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum as an "American Original." In 1927, just out of the Columbia University School of Architecture, Lapidus--who had landed a job as an architectural draftsman at a good firm--started moonlighting designing retail interiors. Within six months he was making more money at night than during the day. "In my store work I was purely interested in commerce," he says. "The goal was to grab a customer walking on the street and say, eHey, come in--I've got something to show you.'" Initially resistant to the idea of full-time retail work ("I had studied architecture, and stores were not architecture"), he ended up spending the next 15 years doing nothing else while developing the "tricks"--theories about what people like and find attractive-- he uses today. "There were three things--took me years to develop--that created an effect which actually stopped people on the street," he says. "The stores depend on brilliant light, the use of color, and one other thing I noticed: people do not make a beeline for the thing they want to buy. They meander. So I shaped the walls in unusual forms." Lapidus's 1950s hotel designs caught the eye of postmodern pioneer Denise Scott-Brown when she visited Miami in 1965. "I was interested in buildings where a whole lot went on--a whole life, you might say," Scott-Brown recalls. "The Fontainebleau was one of those cities in a building." Built in 1954, the Fontainebleau was the ultimate application of his theories, and it was an immediate crowd-pleasing success. Its Busby Berkeleyesque decor evolved from the developer's request for a "French-château style" interior. "That was about the worst thing I could think of," Lapidus says. "French-château style in Miami Beach? I showed him some pictures of French châteaus, and he said, eMy God, are you crazy? You think I'm going to do this old-fashioned French-château style? I want modern French-château style!'" This absurd request gave Lapidus unexpected freedom: "It was a process of slowly brainwashing this man until he thought he was getting what he wanted. I was really creating a style which was pretty much my own." "For people who were using the hotels in Miami Beach, their idea of heaven was a kind of Hollywood silver-screen luxury of the thirties and forties," Scott-Brown says. "That's what he reproduced for the Fontainebleau." Lapidus's curvy buildings, dressed to the nines with over-the-top ornamentation, were the antithesis of Mies van der Rohe's prevailing International Style, and the critics were savage. A 1960 Time article called him "a disciple of excess." "I was ruled out of the architecture profession," Lapidus says. "The Fontainebleau--the high point of my career--was never published. Never." Developer Larry Tisch, who built a number of Lapidus's projects (including the 1956 Americana of Bal Harbor, in Miami Beach, and the 1961 Summit Hotel, in Manhattan), says that the critics missed the point. "I don't think they ever understood him," Tisch says. "He was a showman in addition to being an architect, and if you are building a resort hotel, you need a showman!"

"I believe we really ediscovered' him--that is, talked about him in the kind of educational circles we were moving in," Scott-Brown says, referring to two Yale studios she and her partner, Robert Venturi, asked Lapidus to participate in during the early 1970s. Their admiration started Lapidus's slow climb into respectability, which has included a 1976 show at the Cooper-Hewitt; a long overdue monograph, Morris Lapidus: Architect of the American Dream (Birkhäuser Verlag, 1992); and his latest and greatest honor: the American Original award. He now works in collaboration with Miami architect Deborah Desilets, who convinced him to come out of retirement after 12 years away from architecture. "I thought it would be great to ask him to revisit every project type he ever did," she says. Starting in 1997 with a Toronto store for clothing company Roots, the busy duo has designed a restaurant called Aura, which references Lapidusian forms of the thirties; an unbuilt Miami hotel; a proposed office building; and products such as ties, a pen, and a watch.

"My theories seem to be what the twenty-first century will be like," Lapidus predicts. "Architects now aren't copying me. But you look around, and you see buildings that are colorful and unusual in shape and form. I suppose at my age I'm allowed to be a visionary." [ Edited by: I dream of tiki 2008-04-14 00:06 ] |

|

MH

Mr. Ho

Posted

posted

on

Sat, Feb 21, 2009 8:12 AM

hey miami kin! mr. ho here...i'm in miami for the next couple days (south beach and carless) and wondering if that MiMo tour I noticed was mentioned in this thread is still happening? any other fun mimo recs I wouldn't know about bein a tourist, please shout. I hear the tiki scene is long gone from Miami proper...but can't wait for the beach, mimo, art deco, and some cuban food! saludos, Mr. Ho |

Pages: 1 10 replies

West Avenue, South Beach

West Avenue, South Beach The Carillon

The Carillon The Bacardi buildings

The Bacardi buildings image a 9see below]

image a 9see below] Image b

Image b