Beyond Tiki, Bilge, and Test / Beyond Tiki / Miami Beach Mid-Century Modern officially historic

Post #373564 by I dream of tiki on Mon, Apr 14, 2008 12:00 AM

|

IDOT

I dream of tiki

Posted

posted

on

Mon, Apr 14, 2008 12:00 AM

Morris Lapidus NOTE: This article is out of date because it still speaks of Morris Lapidus as still being alive. Lapidus of Luxury Morris Lapidus By Jonathan Ringen

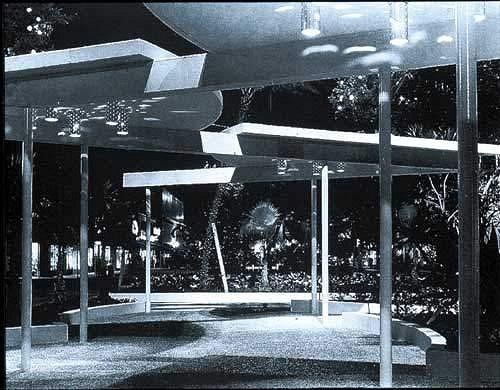

Always a hit with the people, Miami's showman architect has finally wowed the critics, too. Morris Lapidus seems to have a favorite adjective: unusual. Use it, as he most often does, to modify the words shape, form, color, lighting, and adornment, and you get a pretty good summation of the delirious style practiced by the architect of Miami Beach's superglam midcentury Fontainebleau and Eden Roc hotels. "My whole concept of life is to make it more unusual, more interesting, more warm," says the architect who last November both celebrated his 98th birthday and was honored by the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum as an "American Original." In 1927, just out of the Columbia University School of Architecture, Lapidus--who had landed a job as an architectural draftsman at a good firm--started moonlighting designing retail interiors. Within six months he was making more money at night than during the day. "In my store work I was purely interested in commerce," he says. "The goal was to grab a customer walking on the street and say, eHey, come in--I've got something to show you.'" Initially resistant to the idea of full-time retail work ("I had studied architecture, and stores were not architecture"), he ended up spending the next 15 years doing nothing else while developing the "tricks"--theories about what people like and find attractive-- he uses today. "There were three things--took me years to develop--that created an effect which actually stopped people on the street," he says. "The stores depend on brilliant light, the use of color, and one other thing I noticed: people do not make a beeline for the thing they want to buy. They meander. So I shaped the walls in unusual forms." Lapidus's 1950s hotel designs caught the eye of postmodern pioneer Denise Scott-Brown when she visited Miami in 1965. "I was interested in buildings where a whole lot went on--a whole life, you might say," Scott-Brown recalls. "The Fontainebleau was one of those cities in a building." Built in 1954, the Fontainebleau was the ultimate application of his theories, and it was an immediate crowd-pleasing success. Its Busby Berkeleyesque decor evolved from the developer's request for a "French-château style" interior. "That was about the worst thing I could think of," Lapidus says. "French-château style in Miami Beach? I showed him some pictures of French châteaus, and he said, eMy God, are you crazy? You think I'm going to do this old-fashioned French-château style? I want modern French-château style!'" This absurd request gave Lapidus unexpected freedom: "It was a process of slowly brainwashing this man until he thought he was getting what he wanted. I was really creating a style which was pretty much my own." "For people who were using the hotels in Miami Beach, their idea of heaven was a kind of Hollywood silver-screen luxury of the thirties and forties," Scott-Brown says. "That's what he reproduced for the Fontainebleau." Lapidus's curvy buildings, dressed to the nines with over-the-top ornamentation, were the antithesis of Mies van der Rohe's prevailing International Style, and the critics were savage. A 1960 Time article called him "a disciple of excess." "I was ruled out of the architecture profession," Lapidus says. "The Fontainebleau--the high point of my career--was never published. Never." Developer Larry Tisch, who built a number of Lapidus's projects (including the 1956 Americana of Bal Harbor, in Miami Beach, and the 1961 Summit Hotel, in Manhattan), says that the critics missed the point. "I don't think they ever understood him," Tisch says. "He was a showman in addition to being an architect, and if you are building a resort hotel, you need a showman!"

"I believe we really ediscovered' him--that is, talked about him in the kind of educational circles we were moving in," Scott-Brown says, referring to two Yale studios she and her partner, Robert Venturi, asked Lapidus to participate in during the early 1970s. Their admiration started Lapidus's slow climb into respectability, which has included a 1976 show at the Cooper-Hewitt; a long overdue monograph, Morris Lapidus: Architect of the American Dream (Birkhäuser Verlag, 1992); and his latest and greatest honor: the American Original award. He now works in collaboration with Miami architect Deborah Desilets, who convinced him to come out of retirement after 12 years away from architecture. "I thought it would be great to ask him to revisit every project type he ever did," she says. Starting in 1997 with a Toronto store for clothing company Roots, the busy duo has designed a restaurant called Aura, which references Lapidusian forms of the thirties; an unbuilt Miami hotel; a proposed office building; and products such as ties, a pen, and a watch.

"My theories seem to be what the twenty-first century will be like," Lapidus predicts. "Architects now aren't copying me. But you look around, and you see buildings that are colorful and unusual in shape and form. I suppose at my age I'm allowed to be a visionary." [ Edited by: I dream of tiki 2008-04-14 00:06 ] |