Tiki Central / Collecting Tiki / The real beachcombers: Collecting Floats and Other Flotsam PICTURES!

Post #406448 by Tikiwahine on Sun, Sep 7, 2008 11:24 AM

|

T

Tikiwahine

Posted

posted

on

Sun, Sep 7, 2008 11:24 AM

The real beachcombers *Jack Knox Sunday, September 07, 2008*

'Up all night," reads Barry Campbell's log entry for April 14, 1987. "Glass ball fever." He found 36 Japanese fishing floats that time, a personal record. Made a trail of them for wife Barb to follow in the morning. Had to earn his bonanza, though. Leaned into the teeth of a howling rainstorm not long before midnight and trudged Long Beach, 12 kilometres each way, scouring the shoreline. Went through four flashlights picking his way through the washed-up bull kelp, packing crates, shoes and other tempest-tossed jetsam. When he finally got back home with his treasures, it was time to stagger off to work at the national park's Wickaninnish interpretive centre, a sight that must have alarmed the tourists. "I felt I was radioactive because I was glowing so much from the windburn," he recalls. "I was bright red." For this, dear reader, is the brutal beachcombing truth: If you want glass balls, you need an iron will. While the open ocean tosses all manner of unexpected marvels onto the sands of Vancouver Island's west coast, the competition to find the waterborne wonders is as fierce as the weather that drives them ashore.

Anyone who has trod an empty stretch of sand has entertained dreams of exotic discoveries: A message in a bottle, perhaps, or a volleyball named Wilson, or a floating foot. (OK, maybe not a foot.) "It's the excitement and mystery of finding something that's come from so far away, something that's got a story behind it," says Barbara Campbell, eyeing a selection of ocean offerings outside her Tofino home. One of the Campbells' deck chairs was found on a beach. So was their snow shovel. "My laundry basket that I've used for 25 years is beachcombed," says Barbara. They have found downhill skis, sleds, even three worse-for-wear televisions on one day. Most cherished of all by serious beachcombers are Japanese fishing floats. The glass balls are no longer used by the deep-sea fleet, but they still drift in. Some are the size of apples, others as big as beach balls. Spheres, cylinders, rolling pins -- most have the greenish hue of the recycled sake bottles from which they were made, but some are amber or blue. Many are etched with their manufacturer's mark. "Some of these could be 60, 70 years old," Barry says, examining the collection on his deck.

You can actually sniff out a good beachcombing tide, one where the tell-tale odour of rotting seaweed and other flotsam is carried on the south winds hammering in from the open ocean. "It smells like glass balls are coming in," Barry will say. That's when you bundle up head to toe in full rubber rain gear, head out into the elements to be the first on the scene. If another beachcomber's car is already in the parking lot, give up and go elsewhere. "We call that the glass-ball Olympics, when people are dashing here and there to get to a beach." "If you're really dedicated, you stay up all night," he says. That means wading rivers in the dark, or contending with wolves patrolling the shoreline for dead birds and other creatures washed in by the storm. Some beachcombers use inflatable rafts to cross creeks, while others even use floatplanes to reach remote locations. Oak Bay-raised Barry got the beachcombing bug as a boy on outings to French Beach and Port Renfrew with his dad. Never found much, but the possibilities fired his imagination. It was in 1965, as an 18-year-old hiking the West Coast Trail, that he and two UVic buddies were each given a pair of Japanese fishing floats by the Pacheena Point lighthouse keeper, who had found the glass balls that morning. His own first find was in 1967, a five-inch ball picked up off Maben's Beach, facing Pacheena Bay. That was 335 glass balls ago -- more than that, really, since Barry only began recording the family's finds in 1970. That's the year he arrived in Tofino, the fifth person hired to work in what became the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve. He retired in 2002 (at least in theory; he has since put in more than 3,000 volunteer hours clearing the park of broom and other invasive species) which allows more time for the Campbells to poke into out-of-the-way places. They boat over to Flores Island, Vargas Island, other places whose beaches are off the beaten path.

Not many fishing floats wash ashore these days. "For every day you find one, there are probably 10 days that you don't," Barry says. See a glass ball today, it's likely to be a tourist trinket that arrived here on a cargo ship, not a storm-pushed tide. (You can tell the difference: The replicas are unweathered, made of thinner glass, often bound in unworn rope.)

Lots of other stuff comes in, though. Langford-raised Barbara spotted a mannequin once, a U.S. Coast Guard rescue dummy clothed in a survival suit, partly hidden in the driftwood on Vargas Island. At first, she feared it was alive -- or, worse, not alive. All manner of odd bits show up: In the early 1970s it was Transonics electronics, made for the old Woodward's department stores, that showed up on West Coast Trail beaches, having somehow been dislodged in transit. "Drift cards," tossed in the water by oceanographers tracking currents, are picked up, then mailed back to their source, often places in California or Washington state. In 1985, a flotilla of packing boxes came bobbing ashore, each containing 500 graham-wafer-sized sheets of California redwood that had escaped while being shipped to Japan to be made into pencils.

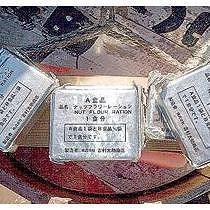

Barry still has some of those boxes in his garage. Not so his collection of 80 or 90 Nikes, part of a shipment of 80,000 that famously washed off a ship off Alaska in 1990. Not just runners, but hiking shoes, too. They were strewn up and down the west coast of the island, residents picking them up, trying to swap with each other for a matching pair. "I think I got one pair of light hikers that were a match." Some people had hundreds of shoes. Alas, some of the footwear had been in the water long enough to have goose barnacles growing on it, and when the barnacles died, well, the Nikes smelled gnarly. "They were pretty stinky." Ditto for the Italian sandals that washed up in the early 1990s. They came in either grey or fluorescent blue, with an air cushion in the sole. "I got dozens of them." The Campbells once came across brick-sized plastic emergency kits designed for Japanese-shipwreck victims, each kit crammed with packages of food ( "The Japanese seed cakes, they were really good," says Barbara) and a note reading "Never give up! Rescue is coming!"

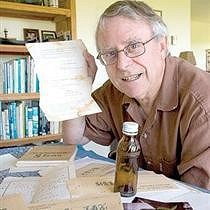

Barry's coolest find was in 1987, while walking Chesterman Beach. He saw a pop bottle, ignored it at first, then decided to backtrack and pick it up, curious as to why its cap had been taped shut. He used tweezers to extract what turned out to be a note from Katano Elementary School in Osaka, Japan. A letter to the school elicited a blizzard of replies from its students, mostly in Japanese, which the Campbells had translated by Tofino's druggist. The students explained that they had celebrated the school's centennial by launching 28 bottles in 1985; only Barry's was found. Also in the bottle were what appeared to be a few small pebbles, but were in fact seeds; one grew into an odd-smelling houseplant that proved a source of curiosity until it died. Barry ended up being interviewed for Japanese television by John Gathright, a Victoria-raised man who had become a well-known media personality in Japan. (Who knew?)

If some finds are the product of midnight foul-weather sleuthing in remote locations, others drop -- or float -- in like manna from heaven, most often when cargo has been swept off passing freighters. Barbara recalls Tofitians swarming Chesterman Beach after a shipping container of cedar shake blocks spilled its contents. Residents were trotting off the sand with full wheelbarrows, only to trot back again on the orders of the RCMP, who said the rightful owners were coming. But when no one appeared to collect the shake blocks, back came the wheelbarrows. Then there was the time a stainless steel refrigerated shipping container washed ashore. Tofitians rubbed their hands in eager anticipation, wondering what treasure could be inside. It was -- ta da! -- salal, bear grass and evergreen huckleberry, bound for florists in New Zealand. To Tofino, it was coals to Newcastle. What a letdown. Much more welcome is the lumber that occasionally gets washed overboard. "Some people basically built their houses with it," says Barry. Snoop behind some Tofino homes and you might find some of the mahogany -- two-metre-long lengths of rough-cut four-by-fours -- that floated in a couple of years ago. The most famous celebrated scavenger hunt came in 1972 after the 473-foot cargo ship Vanlene plowed into Austin Island in Barkley Sound, which its captain had -- oops! -- mistaken for Juan de Fuca Strait. The ship was carrying 300 brand new Dodge Colts, 131 of which were salvaged by helicopter. After that it was open season, the stricken ship swarmed by people who boated over from Tofino, Ucluelet and Bamfield. They made off with lifeboats, linen, tools, doors, furniture -- anything they could, including engines pulled out of the Colts. Alas, being made of pot metal, the engines didn't last long in the damp West Coast. Barry Campbell climbed the ship's ladder to get on board, can still remember the sound of the water sloshing inside the hull. "It was really eerie." At one point, he slipped on the oil-slicked deck, but managed to grab a rail before sliding into the chuck. He rescued a variety of items that now rest in the national park archives: The ship's log, some Japanese editions of Reader's Digest. What appears to be a Morse code guide sits on a shelf of his Tofino home. As for the Vanlene, it broke in two and slid to the bottom, where it became popular among scuba divers.

The last really good beachcombing year was 2003, Barry says. Tighter dumping-at-sea laws mean there's less man-made bits coming in, and that's a good thing. "It wasn't all pretty stuff like glass balls," he says of 2003. "There was lots of Styrofoam and other junk." Unfortunately, much of what does come in has broken away from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, an incredibly huge swath of trash swirling in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, slowly spinning, held together by currents. A recent Georgia Straight story by Roberta Staley described it thusly: "A briny Brobdingnagian mass of bobbing fishing line and nets, computers, bags, shampoo caps, toothbrushes, tires, bottles, diapers, tampon tubes, and plastic containers, the Garbage Patch is estimated to be at least 620,000 square kilometres -- about 20 times the size of Vancouver Island -- and 30 metres deep. Fed by currents carrying garbage originating in North America and eastern Asia -- 80 per cent of it from land, with the rest from ships and oil rigs -- this plastic colossus is growing like a slow cancer." Others say the Garbage Patch is even bigger -- a July story in the Times Colonist said the build-up of plastics is estimated at the size of the U.S. and India combined. Scientists fear an ecological disaster as marine life ingests the confetti-like broken-down plastic. It's a reminder that while it might be fun to pull treasures out of the ocean, we really need to pay attention to what we throw in.

|