Tiki Central / Tiki Travel / Club Nouméa's Tiki Tour of Vanuatu

Post #592045 by Club Nouméa on Fri, Jun 3, 2011 6:18 AM

|

CN

Club Nouméa

Posted

posted

on

Fri, Jun 3, 2011 6:18 AM

Part 1: History and Language

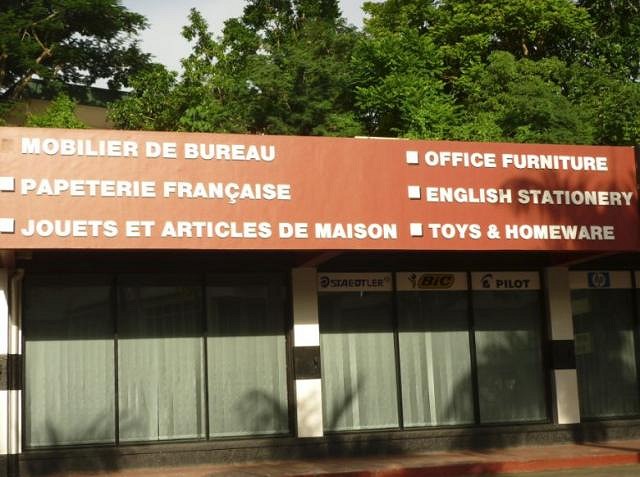

By the first few years of the 20th century, in the days when the European powers' colonial carve-up of the world was almost completed, there remained the issue of what to do about a strange archipelago east of Papua New Guinea and north of New Caledonia, called the New Hebrides. A land of cannibals, castaways, runaways and traders in the 19th century, by the early twentieth century the New Hebrides had coalesced into a loose entity that might start being considered a viable administrative concept if only France and Great Britain could figure out what to do about it. The Europeans who lived there were a motley bunch of French citizens predominantly from France, New Caledonia and Indochina, and British subjects predominantly from the UK, Australia and New Zealand. Neither the expatriate French nor English speakers were there in sufficient numbers to outweigh their rival community, and the islands were not of sufficient economic importance for either France or Britain to contemplate annexing or even partitioning the archipelago. So in 1906 the two empires arrived at a most peculiar compromise: the Franco-British Condominium of the New Hebrides. Neither power would govern the islands - both would. The result was two of everything: a government consisting of two Resident governors with two rival colonial administrations, two justice systems (not forgetting the Native Court system, whose presiding judge was appointed by the King of Spain), two police forces, two prison systems, two currencies, two official European languages, two school systems, and two rival brands of Christianity (Catholicism for the French speakers and various brands of Protestantism for the English speakers). There were even two sets of road rules: on those islands administered by the British, they drove on the left side of the road, and on those islands administered by the French, they drove on the right. This enabled some strange situations to arise. If you were a foreign immigrant to the New Hebrides, you could decide whether you wanted to settle there under French or British law, and whether you wanted to set up your business there under French or British companies law. If you were arrested for some misdemeanour, you could decide whether you wanted to be tried in a French or British court, or whether you wanted to do your jail time in a French or a British jail (the British jail in Port Vila was tidier and better organised, while the French jail had the best food...). Little wonder then that the ethnically and linguistically varied Melanesians who found themselves ruled over by this strange colonial aberration and who came to be educated in Western ways, ended up referring to it caustically not as "the Condominium", but as "Pandemonium". Independence came in 1980, after a minor contretemps instigated by French settlers and their indigenous sympathisers that came to be known as the "Coconut War" ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coconut_War ), resulting in the departure of many French settlers in the early 1980s. The new nation, led by the English-speaking Vanua'aku Pati, made a name for itself in the 1980s as a vigorous critic of France's South Pacific policies, but use of the French language survived, and it is still one of the archipelago's two official European languages, alongside English:

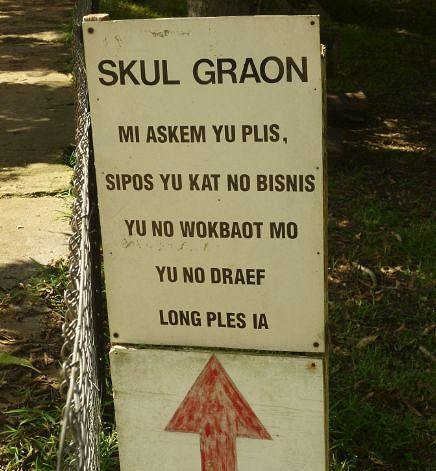

The third official language is a variety of pidgin English that is called "Bichelamar" by French-speakers, and "Bislama" by everyone else. It originally started out in colonial times as a basic lingua franca used by European traders and natives for doing business, and it has since become a national language used for all sorts of things:

Many tourists imagine that speaking Bislama only involves talking baby talk or speaking English for dummies, and come up with phrases like "mi eatem coconut", imagining that they are speaking correctly, when the correct way of saying "I am eating a coconut" is "mi kakae coconus". Similarly, "thank you very much" is actually "tangyu tu mas", and when greeting someone in the street you do not say "good evening", but rather "gud naet". Bislama, although it looks comical to English speakers, is a proper language with its own pronunciation, spelling, syntax and grammar:

Some of this sign is a no brainer if you speak English, but you are not going to be able to decipher all of it unless you know that "sapos" actually means "should" or "if", and that "Pikinini blong yu" actually means "your child". Other things only really make sense if you read them out aloud:

And even linguists who have done a bit of study before arriving can get thrown. At my hotel one morning I was asked: "Yu wanem poelem mo fraenem eh?" To which I replied: "Mi no harem save!" (I don't understand!) I asked the staff member to repeat the sentence a couple of times before I finally got it, but it took a knowledge of 3 languages to crack what she was asking. What really threw me was "eh" which I realised meant "eggs", following which things fell into place: "poêle" is a pot or pan in French, which I took to mean scrambled, "mo" is a Polynesian word meaning "and/or", and "fraenem" means "fried". An assortment of useful expressions in Bislama: Mi go long bush - I am answering the call of nature Mi no go long bush - I am constipated Mi sit sit wara - I have diarrhea No gud man dog! - Bad dog! (useful for dealing with the many strays roaming around) or No gud woman dog! - Bad dog (bitch)! Hemia wan big pig! - That's a big pig! (pigs are a status symbol in Vanuatu's tribal societies - this is the equivalent of admiring a man's car in the US) Hemia wan bigfala pig! - Man, that's a REALLY big pig! (this needs to be spoken in an appropriate tone of wonderment) And if you want to start a conversation with a ni-Van (as the locals call themselves), you do not talk about weather, but rather about family ties and tribal origins: Yu kat waef? Yu kat sista mo brata? Yu kam wea? - Are you married? Do you have a sister or brother? Where are you from? Such questions are not at all nosy, and provide a nice lead-in to a long and friendly chat ... CN

[ Edited by: Club Nouméa 2011-06-03 06:20 ] [ Edited by: Hakalugi - Typo fixed per request. - 2012-01-21 21:19 ] |