Tiki Central / Locating Tiki / The Polynesian (at The Pod Hotel), New York, NY (bar)

Post #787614 by AceExplorer on Mon, Jun 11, 2018 1:45 PM

|

A

AceExplorer

Posted

posted

on

Mon, Jun 11, 2018 1:45 PM

An article from 6/5/2018.

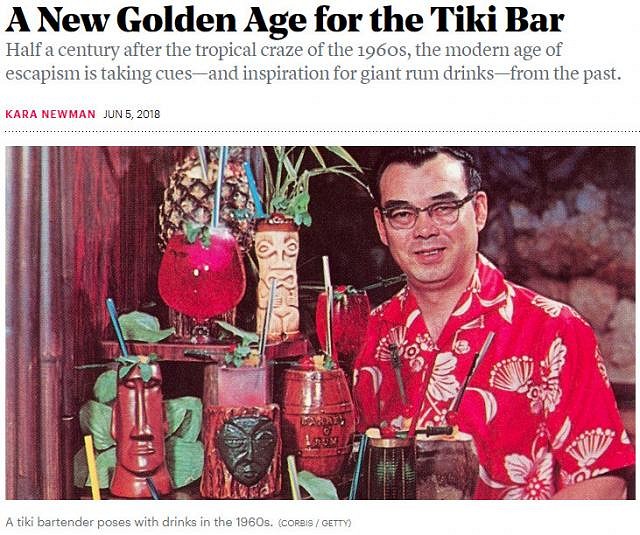

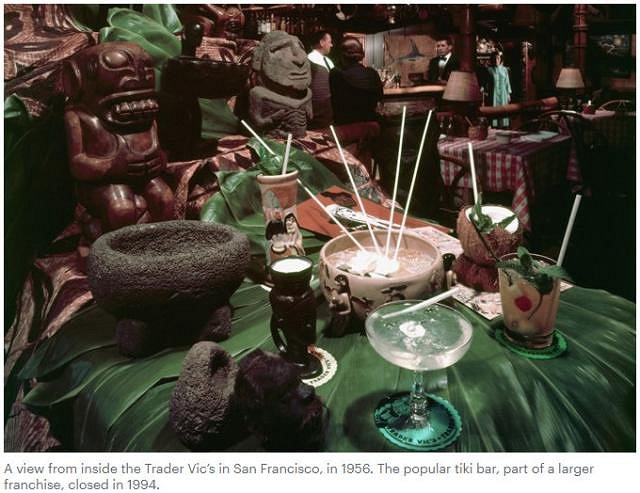

There are no TV screens inside the Polynesian, the giant new tiki bar that opened three stories above Times Square over Memorial Day weekend. That means no news crawls, no Fox & Friends, no jaw-gritting headlines—nothing to break the illusion of a rum-fueled tropical oasis. The Polynesian’s splashy opening signals the arrival of more than just another themed bar serving $15 drinks in skull-head tiki mugs. It’s the manifestation of a certain mood in America: the escalating need for escapism. (The over-the-top drinks are just a bonus.) On opening night, the Friday heading into the holiday weekend, aloha-shirted tiki enthusiasts queued in the lobby of the Pod Times Square hotel, awaiting the grand unveiling. It was an ironic moment that echoed one from almost 30 years earlier, when another sprawling tiki bar inside a Midtown Manhattan hotel closed, ushering in what would be the end of tiki in New York for decades to come. That was when Donald Trump closed Trader Vic’s, a tiki bar in the basement of the Plaza Hotel, which Trump then owned, deriding it as “tacky.” Today, the tumult surrounding the Trump administration has helped reinvigorate the tiki machine. The original tiki movement grew out of a similar sense of unease, says Martin Cate, a tiki historian and the proprietor of the tiki bar Smuggler’s Cove, in San Francisco. Don the Beachcomber, the tropical-themed café in Hollywood that set the template for the modern-day tiki bar, opened in the 1930s, in the middle of the Great Depression, Cate notes. “It offered a sense of a escape,” he says. “It was an imagined South Pacific, a transportive journey outside of the Depression.” America’s tiki obsession hit its golden era in the postwar years, continuing into the 1950s and ’60s. After World War II, servicemen carried home stories of faraway Pacific lands. Among those returning was the author James Michener, a former naval reservist, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1948 for his book Tales of the South Pacific. Rewritten as a musical, South Pacific became first a Broadway hit, then a movie sensation in 1958. Hawaii became the 50th U.S. state in 1959. Two years later, Elvis Presley released Blue Hawaii, setting off a fresh wave of enthusiasm for island culture. And thanks to developments in commercial aviation, more Americans were able to visit the actual South Pacific. In particular, tourism to Hawaii thrived. Tiki bars continued to provide a sense of escape, but during this economic-boom time, they acted as “a dramatic counterpoint to the go-go sense of progress, big money, chrome and steel and future and space age,” Cate explains. “Maybe I want to loosen my tie and forget about the rat race. Or the flip side of all that advancement—the constant threat of nuclear war that loomed over America as this existential threat throughout the 1950s.” It’s not a coincidence that Sven Kirsten, who wrote The Book of Tiki, called tiki bars “the emotional bomb shelter of the Atomic Age.”

This all sounds eerily familiar: Tensions with North Korea have put the threat of nuclear war back in the headlines. Study after study shows that Americans feel overworked and chronically stressed. Meanwhile, smartphones make tuning out work obligations and worrisome news harder; for many, “out of office” no longer equals “off duty.” Added to that, social media amplify the chatter of headlines and arguments, often churning up anxiety and discontent. The trappings have changed, but the “go-go sense” remains. “Maybe we’re not in the recession anymore,” Cate says. “But we’re back to those original feelings.” No wonder tiki bars are booming again. Yet tiki—a catchall term for mid-century-inspired homage to all things tropical and vaguely Polynesian—has evolved in recent years. For one thing, tiki has gone from being an appropriation of actual Polynesian culture to becoming an adaptation of that earlier appropriation. (More on that in a moment.) For another, the scrappy and kitschy are increasingly giving way to the luxe and well funded—in other words, 21st-century tiki is escapism, capitalized anew. A growing number of deep-pocketed restaurant groups now back successful tiki enterprises. In Orlando and Anaheim, California, Walt Disney World and Disneyland each have a Trader Sam’s outpost, a relatively kid-friendly take on the tropical-bar concept. Chicago has Three Dots and a Dash, a sprawling space in the downtown business district, as well as Lost Lake, a more intimate bar in the hip Logan Square neighborhood. But Tiki bars don’t have to be high-end productions to transport patrons from daily worries. Most major cities have seen new tiki bars launched within the past few years, from Latitude 29 in New Orleans to Hidden Harbor in Pittsburgh and Hale Pele in Portland, Oregon. Even cities that don’t have tiki bars often have popular tiki nights hosted within existing establishments. Among big-ticket tiki, the Times Square Polynesian is the latest—and arguably most expensive—example, launched under the umbrella of Major Food Group, which runs such concepts as The Grill/The Pool in the former Four Seasons space, ZZ’s Clam Bar, and Carbone. With the exception of the Trader Sam franchise, the Polynesian, launched within a hotel, also seems the most explicitly targeted to tourist traffic. It’s a particularly lavish, theatrical experience. The 200-seat indoor/outdoor space features an intricately carved wooden bar topped with lava stone glazed an oceanic turquoise. A “pirate room” is secreted away in the back, centered around an enormous round table topped with a pirate’s map of Polynesia and illuminated by an oversize, gilded hanging lamp shaped like an inverted cocktail coupe. It’s not hard to imagine the space for corporate meetings; it’s even easier if you imagine all the corporate honchos wearing eye patches. Adding to the drama, Brian Miller, a co-owner, bartender, and self-declared “pirate,” presides over the operation, cutting a Jack Sparrow–esque figure in his trademark sarong and tricornered hat. According to the Mariners’ Museum, pirates are associated with the Caribbean in the late 17th and 18th centuries, not Polynesia, adding to the tropical mash-up. The revelers at the Polynesian may be more interested in rum drinks than a history lesson, yet allegations of cultural appropriation have long dogged the tiki industry. Tiki was, after all, a key export of the tourist culture built upon the stolen Kingdom of Hawaii, which was a by-product of Hawaii’s transformation from sovereign nation to U.S. territory to state. Is a respectful approach even possible? Yes, insists Shelby Allison, a co-owner of Lost Lake, in Chicago: Today’s tiki is “more conscientious and more considerate,” she says. “We’re able to leave behind the old tropes that were problematic in tiki bars of yore.” Others, including Miller, hope to sidestep implications altogether: “I don’t want to get into arguments. I don’t want to talk about cultural appropriation. I’m not looking to fight,” Miller says. “We’re not about that ... I want to bring tiki to more and more people. We’re just trying to honor the culture and shine a light on tiki cocktails.” For Miller, the Polynesian is the culmination of several years of hosting semisecret tiki nights at venues across Brooklyn and Manhattan. The cocktail menu features some of his original cocktails, such as the derelict, a potent, banana-spiked sipper featuring a quartet of rums; the playlist, which on opening night bounced from reggae to Run-DMC, is also his. “Hopefully down the line we are the greatest tiki bar in the world,” he told me. Although the Polynesian-branded glassware isn’t (yet) available for sale, it’s a reminder that merchandising also is part of the tiki-bar economy. For example, Jeff “Beachbum” Berry, the proprietor of Latitude 29, has his own line of tiki merch on the website Cocktail Kingdom. Similarly, Chicago’s Lost Lake sells mugs, T-shirts, even “garnish kits” for decking out cocktails at home. The mai-tai mug is a particularly strong seller, Lost Lake’s Allison reports. “Mugs are a huge source of revenue for tiki bars,” Allison notes. It also helps offset the cost of theft, she says, a problem many tropical-themed bars face, thanks to patrons seeking souvenirs. “No one is stealing coupe glasses at Death & Co,” a speakeasy-style bar in NYC, “but at least five ceramic pieces walk out my door every Saturday night.” Although it’s difficult to pin an exact number on how much money is spent on chasing escapism through tiki bars; conferences such as Tiki Oasis, in San Diego, and the Hukilau, in Fort Lauderdale; or exotica music and loud floral-print caftans, it’s abundantly clear that tiki is in yet another golden age. Americans are still finding refuge in spaces that bring the pageantry of flaming cocktails to the forefront, and push TV screens and the ever-frenzied news cycle deliberately out of sight. Of course, nothing is stopping patrons from pulling up Politico or CNN on their phone. But a quick glance around the Polynesian reveals that everyone’s too busy Instagramming blue drinks in fishbowls to check the latest headlines anyway. KARA NEWMAN reviews spirits for Wine Enthusiast magazine. She is the author of NIGHTCAP: More Than 40 Cocktails to Close Out Any Evening. |