Tiki Central / Tiki Travel

Club Nouméa's Parisian Tiki Tour

Pages: 1 17 replies

|

CN

Club Nouméa

Posted

posted

on

Mon, Jun 8, 2015 4:31 AM

Beneath the Paving Stones there's a Beach...

Sous les pavés, la plage... An expression from May 1968, when protesting students began noticing the sand used as a base layer beneath the Parisian paving stones that they were prising up in order to throw them at French riot police. The slogan became ubiquitous, suggesting that life could be something better than the cold hard 20th-century realities offered by the technocratic Fifth Republic. It was in keeping with the escapism espoused by past generations of French thinkers, from Diderot through to Loti. On the face of it, Paris is not a prime destination if you are interested in the South Pacific. It is literally as far away from the South Pacific as you can get without leaving the planet. From New Zealand, a typical travel time from door to door, including time spent in transit and catching public transport in-between the 3 or 4 flights required to get to Paris, is 35 hours. If you fly in via Frankfurt (cheaper airfares), it can take as much as 40 hours. It is with a wry smile that New Zealanders overhear Americans in Paris, complaining about their terrible jet-lag after an 8-hour flight. I first travelled to Paris in 1991 as a student doing thesis research on the French Pacific (Paris has better libraries and archives than the French Pacific does) and when I arrived I was completely zonked out. The plan was to check into a cheap student hostel, but the catch was you couldn't book in advance; you just had to roll up and take your chances. I ended up in a hotel for the first couple of nights before finally shifting into one of the hostel's Dickensian dormitories in the Latin Quarter. It was cheap, but it was also winter, it was cold, and it was grim. I felt perpetually tired from lack of sleep. I have never stayed in a dormitory ever since - there's always a snorer, there's always some drunk who staggers in at 2am falling over the furniture, or some lothario who decides to bring his girlfriend back for some late-night entertainment. The homesickness was broken by long-distance phone calls home. I soon discovered that most Parisian public phone boxes were useless as they were located on busy intersections and you couldn't hear a thing for traffic noise. It was not long before I discovered there were two phone boxes on a quiet back street called Rue Monsieur Le Prince:

This is where they used to be - with the 21st-century advent of cell phones, public phone boxes are a dying breed in France these days. It was on one of those walks to call home that I discovered La Librairie du Pacifique (the Pacific Bookshop), just up the street, at number 32 Rue Monsieur Le Prince. This is what it looks like today: sadly, it is the chi-chi Parisian antithesis of what the bookshop was all about:

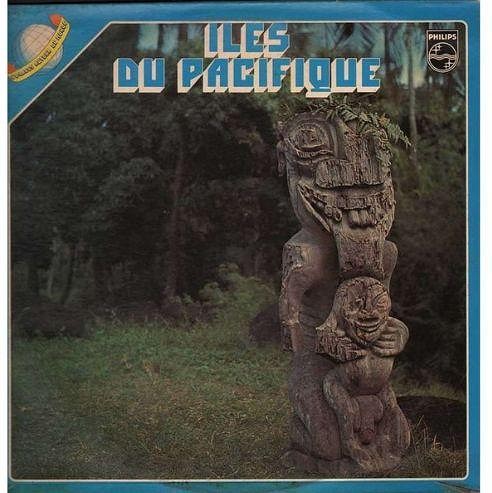

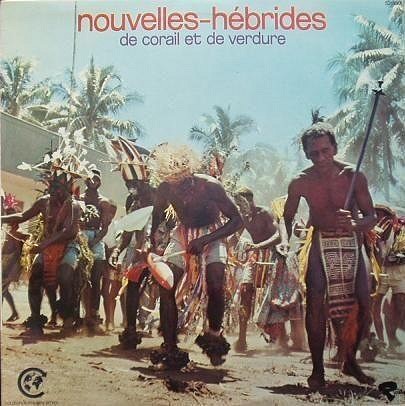

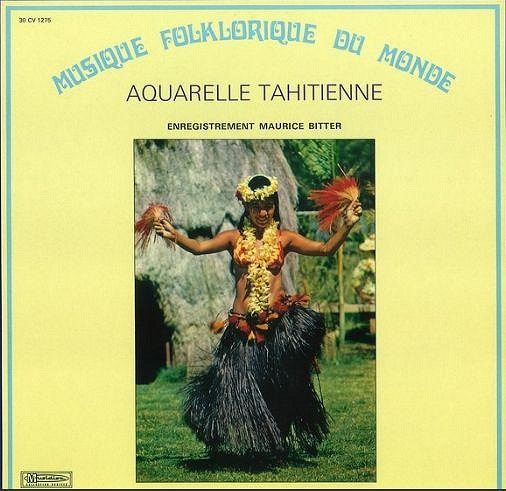

The Librairie du Pacifique stood out from its drab surroundings - the frontage was painted a bright aquamarine blue. There were Tahitian necklaces in the window, tikis inside the doorway, and once you pushed open the door tentatively, the owner seem to pop out from nowhere with a warm greeting. I was greeted by a big barrel-chested gentleman in a Tahitian shirt and chatted to him about New Caledonia as I tried to take everything in. The shop itself was staggering, being packed to the ceiling with all sorts of books about the South Pacific, as well as records, tiki carvings for sale, and other trinkets and odds and ends. Here is a link with some photos of the owner, Maurice Bitter, and the interior of his shop: http://www.christianschoettl.com/article-maurice-bitter-la-librairie-du-pacifique-111457579.html From my first encounter with him, I was aware that M. Bitter was one of those gentlemen you only infrequently encounter in your lifetime. From his knowledge of the Pacific and his amazing collection of books, it was clear he was a great traveller and he knew his stuff. It was only later that I found out the true breadth and scope of his life experience. I guessed from his French accent and his surname that he was probably from Alsace but have not been able to confirm this since. I did not know at that time that he was also Jewish and, from what I have found out, had a rough time as a young man during World War II. He went on to work for the French public broadcasting corporation ORTF and, by the early 60s, was a broadcaster and sound recordist. It is no accident that he recorded the Adolph Eichmann trial in 1961, after the prominent Nazi had been abducted from Argentina by the Mossad and brought to Israel to be tried for his crimes against humanity. It was during these years working in broadcasting that Maurice Bitter travelled. The ORTF was a global organisation, serving the whole French-speaking world. He ended up recording over 50 LPs of field recordings, from a Haitian voodoo ritual, through to music from places like Ceylon, Laos, Cambodia, Peru and Bulgaria. But the greater part of his recordings were devoted to his true love, the French Pacific:

I am going to blow a horn and call him the French Alan Lomax, because of all the ground he covered and the sheer scope of his releases. Here is a sample of just one of his field recordings, of a young Tahitian singing a song called "Te Uru" (Breadfruit): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QiqZ-Jqxr-I That's Maurice at the end, asking the singer about the song... Maurice Bitter also wrote and published various books on the French Pacific. Sadly, he died over ten years ago. He was a gentleman and a scholar with a great love for the Pacific Islands who deserves to be remembered more widely beyond the people whose lives he touched. Whenever I go to Paris, I still frequent the Asian restaurants along Rue Monsieur Le Prince and, walking past number 32, I pause to remember the warm Pacific-style greeting he gave me when I walked into his bookstore as a young student.

[ Edited by: Club Nouméa 2015-06-08 04:58 ] [ Edited by: Club Nouméa 2015-06-09 15:32 ] |

|

CN

Club Nouméa

Posted

posted

on

Tue, Jun 9, 2015 3:06 PM

Cannibals in the Gardens - The Paris Colonial Exhibition of 1931

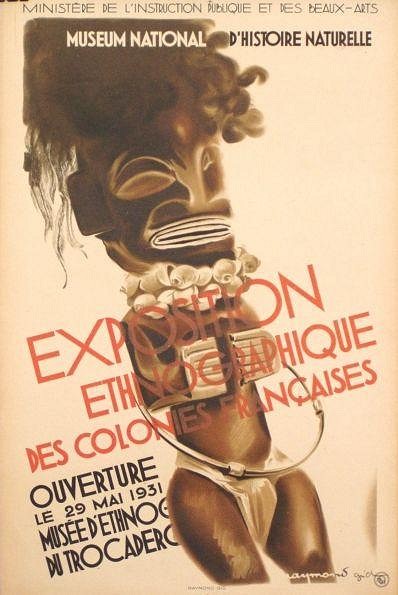

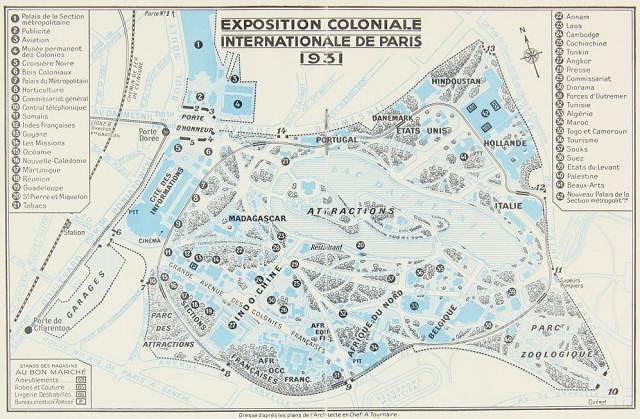

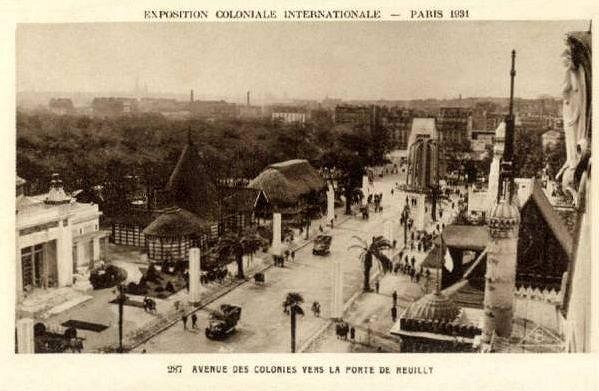

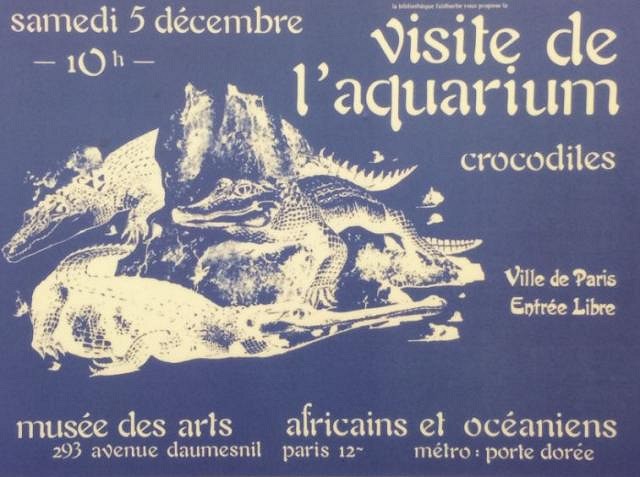

(Poster advertising an exhibition held at the Trocadero Ethnology Museum to coincide with the Paris Colonial Exhibition of 1931.) The Paris Colonial Exhibition of 1931 was a showcase staged by the French Third Republic to show metropolitan French citizens the length and breadth of their colonial empire. Its origins date back to 1913, but the real impetus for it only came once the British Empire Exhibition was held at Wembley Stadium from 1924 to 1925. The success of the British event prompted various French leaders to begin taking concrete measures to bring it to fruition to demonstrate that France too had an empire that it could be proud of. As it turned out, by the time the event opened on 6 May 1931, France was grappling with the Great Depression, and the event came to be seen by various of its critics as a "bread and circuses" event to take the minds of the masses off their financial troubles. The exhibition grounds took up the Bois de Vincennes, on the south-eastern edge of Paris:

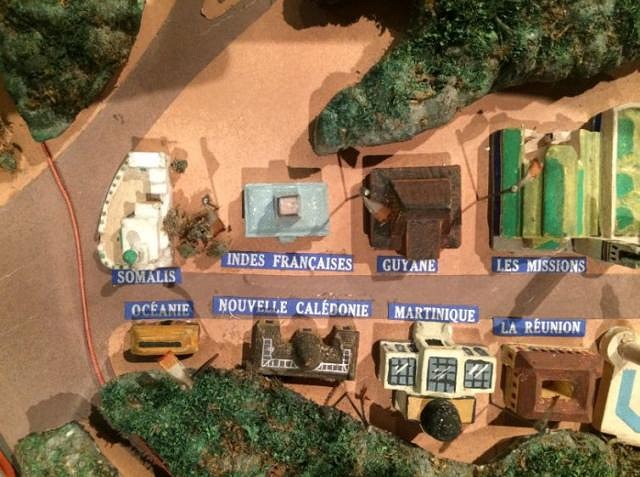

The park provided the setting for pavilions from the various parts of France's empire, including the French Pacific:

The largest French Pacific pavilion was New Caledonia's:

It featured a mix of French architecture and the traditional tall beehive shape of a Kanak hut:

Alongside it was the "Oceania" pavilion, representing the islands of what are now called French Polynesia and Wallis & Futuna:

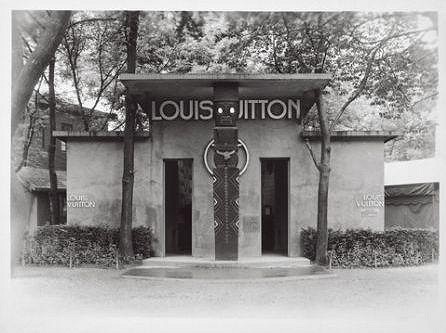

Note the two Marquesan style tikis at the entrance. Around 8 million people visited the exhibition by the time it closed on 15 November 1931 and this was the first time that such a large number of French (and European) visitors came into contact with Polynesian and Melanesian culture. Tikis were not limited to the Oceania pavillion. Various French companies had their own private pavilions. Here is the Louis Vuitton one:

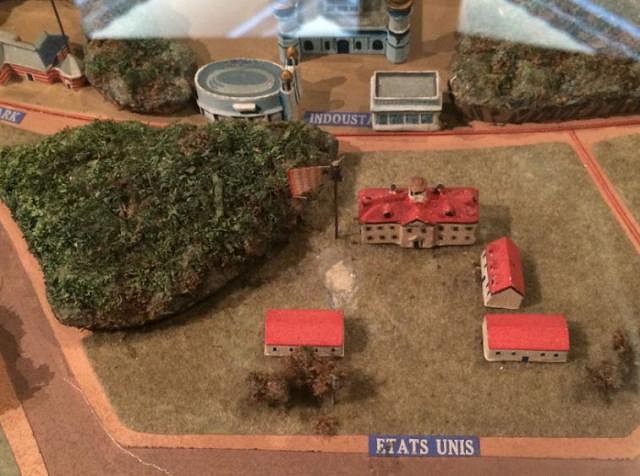

The United States also had its own pavilion, and its Pacific territories were represented there, although I have not come across any evidence of whether there were any tikis on display. Here is a model of the US pavilion, the main building of which was a recreation of George Washington's house:

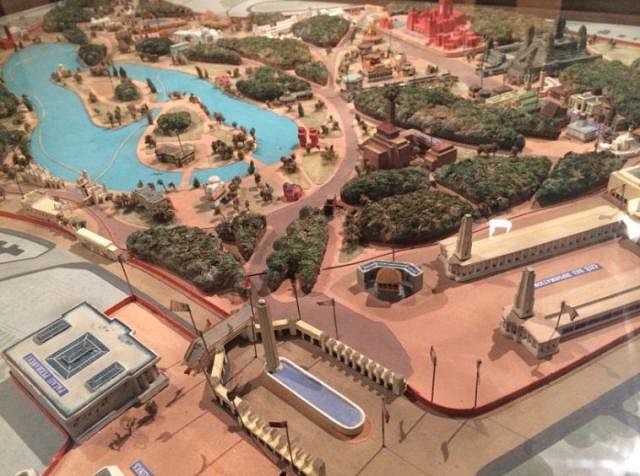

And a general view of the grounds from the main gate, with the New Caledonian and Oceanian pavilions on the far right of the photo:

These latter two buildings were near a secondary gate to the south of the main gate:

The buildings were all cleared away when the exhibition closed its gates in November 1931, with one exception:

This Art Deco masterpiece, in a French colonial style, was originally the exhibition's main building. After 1931, it was used to house a permanent collection of African and Oceanian art, and was still being used in this capacity when I first visited it in 1993. The frontage of this building is quite striking, featuring a bas-relief showing images of the French colonies.

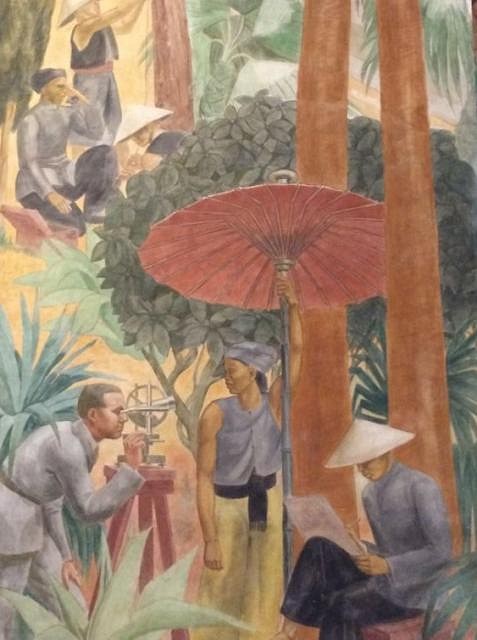

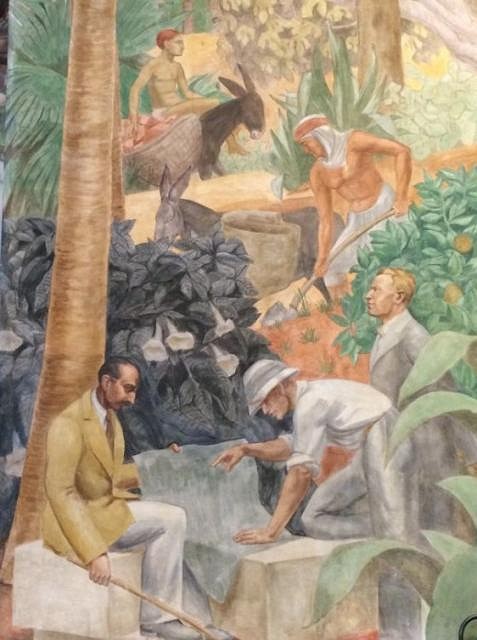

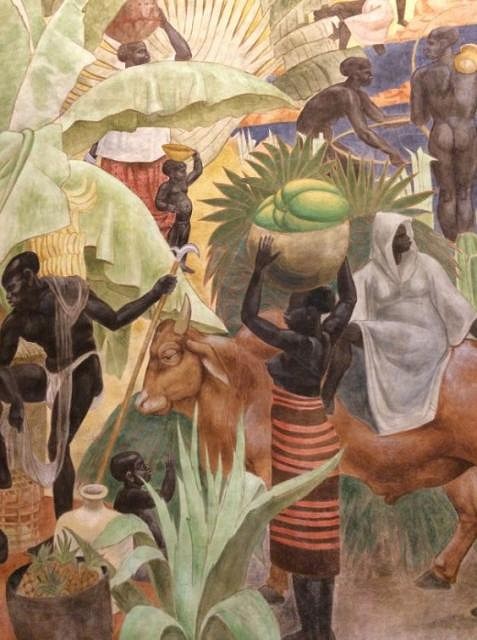

By the early 1990s, due to its colonial origins, this museum had become the black sheep of Paris's State museums. Its days were numbered, which was one of my reasons for visiting it when I did. With a French doctoral student who was also researching the French Pacific, we travelled across Paris from Pigalle to visit this colonial showcase. And what a marvel it was. This is the main hall, still intact, although minus its exhibits now. Originally this room was filled with huge Papuan, Vanuatuan, New Caledonian, Maori and other totemic carvings and structures, surrounded by these mural depictions of the multitudinous benefits of France's civilising mission:

As if all this was not wonderful enough, the basement of the building housed an aquarium, which featured a crocodile pit:

I remember when we got back to my French friend's apartment (she was living with her aunt, uncle and their daughters) and she was telling the two amazed little girls there: "we have to go together - there are crocodiles there!" Fortunately, the aquarium is still there, and it too is decked out in period style:

Sure enough, the crocodile pit is still there:

And it is inhabited:

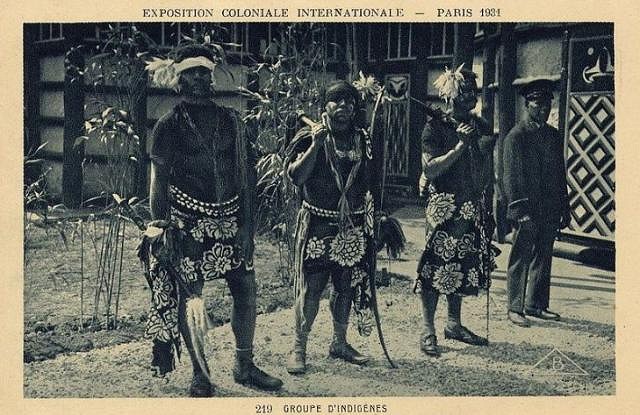

Although its current residents are in fact American alligators, bred and raised in France. The Paris Colonial Exhibition of 1931 had some other supposedly wild denizens. Showcased alongside the crocodiles in the main building were native inhabitants from the various colonies, portrayed by the event's promoters as "savages" and "cannibals". The largest contingent consisted of 111 Kanaks from New Caledonia:

Here's a group shot of the bulk of them, dressed in their street clothes when they arrived in Paris. And here is how they were presented at the exhibition:

These people, who volunteered to travel to metropolitan France to showcase their culture, were dismayed at the treatment they received upon arrival, being told that, since they were being exhibited as cannibals, they should behave more fiercely and savagely. Worse, some of them were shipped across to the other side of Paris to be exhibited in an animal cage in the Bois de Boulogne and, as part of an even shadier side deal, in April 1931, various of them were forced to perform in the Hazenback circus in Germany. These scandalous circumstances were revealed by Alain Laubraux, a New Caledonian reporter who came to cover the exhibition. In his report, he pointed out the great irony that all of these supposed "savages" spoke French and, in New Caledonia, various of them actually worked in government departments like Customs, the Printing Office, etc. His coverage resulted in New Caledonia's Governor receiving an early retirement, although it is hard not to conclude he was not the only one to blame for what transpired. To show that the Kanak contingent's time at the Paris Colonial Exhibition was not all in vain, and that they did succeed in showcasing their culture whilst in Paris, in spite of the idiocy of various of their Parisian hosts, here is a link to various field recordings made of them performing in 1931: http://gallica.bnf.fr/html/und/enregistrements-sonores/nouvelle-caledonie-oceanie Out of curiosity, after revisiting the museum building (now being used for the Museum of Immigration), I dodged the traffic and wandered over to the Bois de Vincennes to see if I could find the site of the New Caledonian and Oceanian pavilions. As I approached the corner of the park in question, it became apparent this was a wild, abandoned section of the park:

Shortly after taking this photo, I came up against a wire fence and had to backtrack and go around a bit to get to what used to be the south gate, where I found....

A truck stop! With the two security guards watching me warily (Paris is currently in the grip of a terrorist scare, with 10,000 troops guarding various public buildings), I stopped in front of the gate just long enough to take this photo of the approximate location of the New Caledonian and Oceanian buildings:

And, for posterity, captured this guy snoozing in the shade of a container. In his defence, it was a particularly hot day, and I retreated to the shade of some trees in the park afterwards for a well-deserved rest myself.

[ Edited by: Club Nouméa 2015-06-09 15:13 ] [ Edited by: Club Nouméa 2015-06-09 15:17 ] |

|

M

MaukaHale

Posted

posted

on

Tue, Jun 9, 2015 4:14 PM

I always enjoy reading your posts. They are so fascinating. |

|

F

finky099

Posted

posted

on

Wed, Jun 10, 2015 3:30 PM

I second that. Great posts, Club Nouméa. I enjoy all the photographic accompaniment. I'm a complete "nerd" for "then and now" photography and find it fascinating, whether they are locations I know or locations I'm seeing for the first time. Great you were able to track down the location and other information on the Colonial Exhibition. I've never even heard of it until now! |

|

T

tripower

Posted

posted

on

Thu, Jun 11, 2015 5:49 AM

Another great post! Please consider writing a book about your travels. |

|

T

tikilongbeach

Posted

posted

on

Thu, Jun 11, 2015 8:50 AM

Wonderful post! |

|

CN

Club Nouméa

Posted

posted

on

Sun, Jun 14, 2015 10:34 AM

Thanks for the positive feedback :) I would love to write a book or three about the French Pacific. The trick is to find a publisher... More to come about Paris: the next instalment will be about St.-Germain-dès-Prés.

[ Edited by: Club Nouméa 2015-06-14 10:36 ] |

|

CN

Club Nouméa

Posted

posted

on

Thu, Jun 18, 2015 3:53 AM

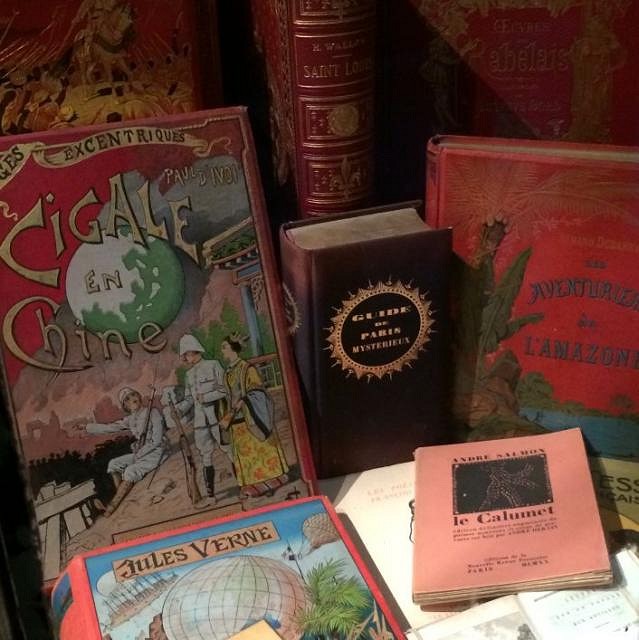

An evening out in St.-Germain-des-Prés

We start in the Rue Dauphine, just before dusk, at what is now the Hôtel d'Aubisson, at No. 33. The basement of this building used to be the location of Le Tabou, an exotic bar that opened in 1947 and was popular with the Left Bank intellectuals, jazz fans and night owls. Virani has already featured this place on Tiki Central, so here is the link: http://www.tikicentral.com/viewtopic.php?topic=43458&forum=2&hilite=virani St-Germain-des-Prés has long been a location for exotic art, which I first noticed in the early 1990s whilst walking around the neighbourhood. The back streets between the Boulevard St. Germain and the Seine have a large number of boutique art galleries and art dealers that still sell "primitive" art. Window-shopping during the daytime tends to be an ordeal at these places due to all the refractory glare you get - not off the glass when photographing I hasten to add, but from the gallery owners. And woe betide rubber-necking tourists wanting to take photos. Should you be seeking the dictionary definition of "snooty", in the absence of words, a photo of a Left Bank art gallery owner would probably suffice. Consequently, the evening is the best time to peruse these places, once the owners have gone home. While most of the "primitive" art on offer tends to be African, I did spot two galleries in the neighbourhood selling South Pacific carvings (doubtless at very high prices although these places seldom if ever feature price tags).

This one was selling some Kanak maces from New Caledonia.

And this one had a Maori walking stick, displayed upside down for some reason, and quite a way away from the window (hence the blurred photo). This neighbourhood is worth having a look at if you are after antique or recent books about exotic places too:

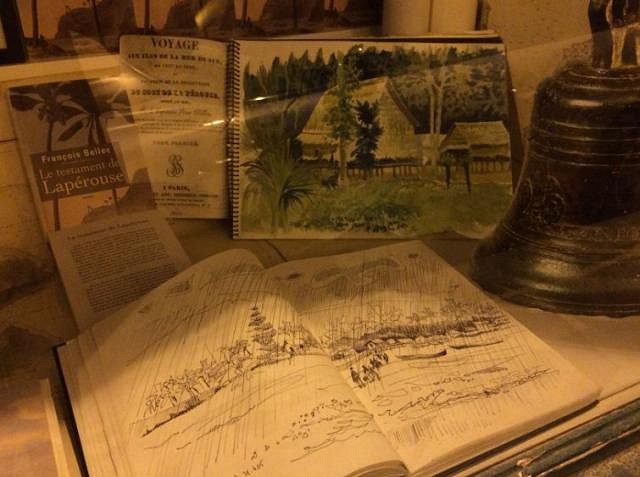

The Librairie Maritime d'Outremer (Overseas Maritime Bookshop) was also promoting a recent publication about the travels of Lapérouse:

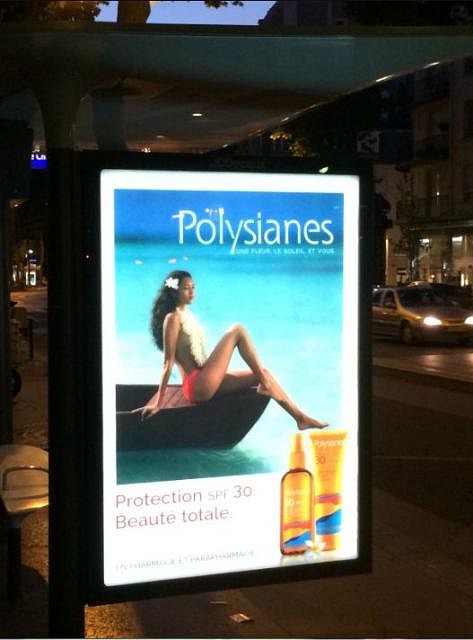

Lapérouse was a French naval officer exploring the Pacific who went missing, along with the two ships he commanded, after sailing from Botany Bay (Sydney) to New Caledonia and on to the Solomon Islands in 1788. It was not until 2005 that a French expedition to Vanikoro atoll in the Solomons formally identified two shipwrecks there as Lapérouse's vessels. Crossing the Boulevard St. Germain, I also came across this reminder of the South Pacific:

Nearby is a 1960s style bar and grill called Le Basile:

They have a small yet functional list of exotic cocktails on offer. Their Cuba Libre was quite nice, as is the décor.

As a concluding note, probably the best option if you are looking for South Pacific carvings is to hop on the Métro and get off at Porte de Clignancourt and head north to the St.-Ouen flea market. There is one shop there that sells carvings from Papua New Guinea:

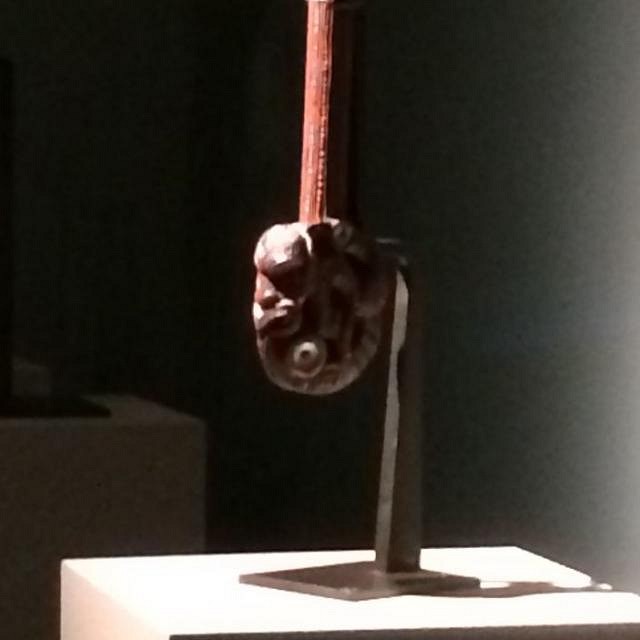

You may also come across other stuff wandering around the various stalls, although this seems to be the only dealer there that specialises in South Pacific carvings. My next instalment concerns the long and sorry tale of a Kanak chief's head....

[ Edited by: Club Nouméa 2015-06-18 04:02 ] |

|

CN

Club Nouméa

Posted

posted

on

Tue, Jul 21, 2015 5:53 AM

The Tale of Chief Atai's Head

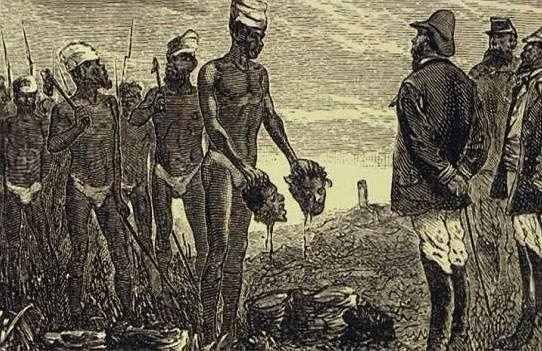

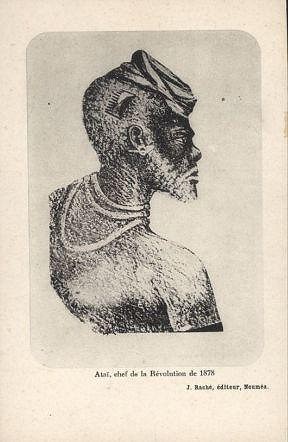

Every year in June, the French charity Emmaüs holds its annual bric-à-brac fair at the Expo Centre at the Porte de Versailles, on the south-western outskirts of Paris. If you are ever in Paris in June, this is a must-see event: 23,000 m2 of second-hand stuff from around 150 Emmaüs branches from all over France and as far away as England and Ukraine. That Sunday (14 June), I got there fashionably late (1 hour), only to witness various people walking out with all sorts of amazing finds, from an electric guitar, through to 1960s Danish furniture, through to a cool fin de siècle birdcage and a strange dwarf-sized tailor's dummy which, in the right domestic setting, would nonetheless have looked quite striking. In front of me in the queue, one Parisian woman was exclaiming "they're taking all the good stuff!" while another behind me was muttering "there'll be nothing left..." However the event's stock of goodies was far from exhausted even though I was an hour late. I went there with one mission: to find French Pacific stuff. Coming from the other side of the world, I was not going to buy any of the incredible period furniture, the amazing array of clothes that would have taken up too much room in my limited baggage allowance, or indeed any of the very varied but somewhat heavy vintage books on offer along with, among other things, everything from vintage radios through to a whole stand of Chinoiserie items presented by Emmaüs's Niort branch. Alas, although there was a surfeit of African carvings and trinkets on sale, I only found one item from the French Pacific, but it was a striking find: a carving of chief Atai's head, clearly based on this engraving, which is familiar to students of New Caledonian history: " In 1878, Chief Atai led a Kanak rebellion against French authority in New Caledonia. It was the closest any of New Caledonia's indigenous leaders ever came to toppling French rule in what, at that time, was a penal colony to which the French Republic transported its petty criminals and revolutionaries, ranging from pickpockets, burglars and whores, through to revolutionaries like the Communard Louise Michel. Ultimately however, Chief Atai's rebellion failed, and he and his witch-doctor were decapitated and their heads were presented to the victorious French commander:

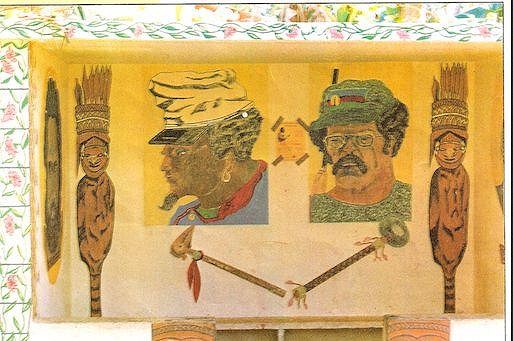

Subsequently, after being placed on public display in Nouméa, Chief Atai's head was shipped off to Paris in 1879 in a jar filled with formaldehyde, and it was added to the collection of the Trocadero Ethnography Museum. The head was even placed on public display there in 1889; an object of curiosity - the remains of the savage chieftain who had dared to challenge French authority. In 1951, Chief Atai's head was transferred to the Museum of Mankind at the Palais de Chaillot, following which it was supposedly lost for many years. In the 1980s, Kanak claims for independence from France had resurfaced to the point that once again they were openly challenging French authority, and Atai was a major inspiration and role model for them. His image featured prominently in pro-independence iconography, such as this bus shelter at Poindimié, where he is depicted alongside Éloï Machoro, a Kanak leader who was shot by two French gendarme snipers in 1984:

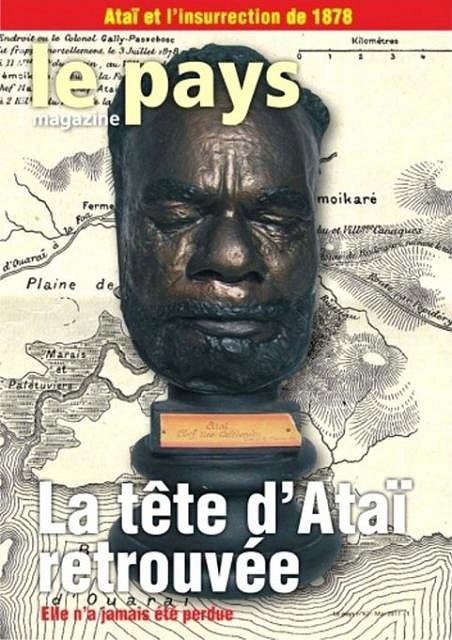

By the late 1980s, the Kanak independence movement retreated from violence and concluded the Matignon Accords with France and local French loyalists, which opened the way to a more peaceful period in its history marking a gradual move towards greater autonomy and ultimately independence which has continued until this decade. Some time between now and 2018, an independence referendum will be held in New Caledonia in order to determine whether it remains part of the French Republic. Since the 1980s, Kanak leaders have been making ever more pointed claims for the return of Chief Atai's head, a particularly painful reminder of French humiliation. For years, various Parisian officials insisted that the head had been lost, until...

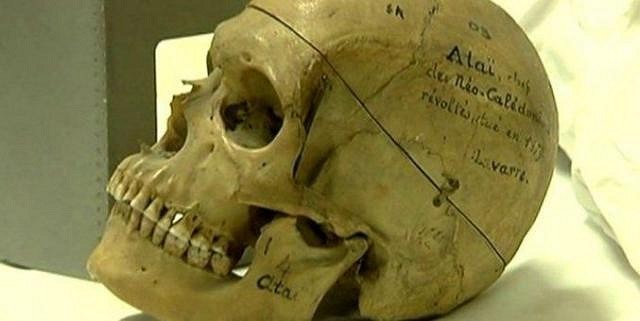

In 2011, a researcher at the Museum of Mankind in Paris revealed that Atai's skull was sitting in a cupboard on the premises:

After 3 years of lobbying by descendants from his tribe, the skull was eventually officially returned to New Caledonia in September 2014, with all due ceremony, by the French Minister of Overseas Territories, thereby closing one of the most inglorious chapters in French colonial history.

[ Edited by: Club Nouméa 2015-07-21 06:04 ] |

|

M

MaukaHale

Posted

posted

on

Tue, Jul 21, 2015 8:10 AM

A great find and story of barbaric times. |

|

CN

Club Nouméa

Posted

posted

on

Fri, Aug 14, 2015 6:16 AM

The Long March: From Bercy to Belleville

On the Champs Élysées, just beside the Grand Palais, is this unmistakable statue of General de Gaulle, head of the Free French in World War II, who offered the following words upon strolling along the aforementioned avenue in 1944:

"Paris The first time I heard those words spoken by de Gaulle in scratchy period film footage screened at a French conference on colonialism and decolonisation many years ago, certain Frenchmen watching the film (learned scholars), began spontaneously declaiming the lines. Others were on the verge of tears. This was a conference where the keynote speaker was Pierre Messmer who, prior to being a key figure in the French decolonisation of Africa in the 1950s and 1960s, had been an officer in the Free French forces that fought Rommel in North Africa, and who took part in the liberation of Paris. In August 1945, he was parachuted into occupied Indochina as de Gaulle's envoy and spent two months being held captive by the Viet Minh before escaping. The French Pacific played a small but key role in the Free French forces, being among the first French overseas territories to rally to de Gaulle's government in exile in London. The very first overseas French territory to rally to de Gaulle was the New Hebrides on 22 July 1940, only a few weeks after the fall of France (it was actually a Franco-British Condominium - see my Tiki Tour of Vanuatu for further details). The New Hebrides were followed by French Polynesia on 2 September 1940 and New Caledonia on 19 September 1940. A Pacific Battalion was raised and sent to North Africa to fight the Germans and Italians. It took part in the Free French break-out at Bir Hakeim in June 1942, and later fought in Italy and in France. Here is some vintage film footage of the unit (start at 2.40, or just zip forward to 7.30 if you want to see Tahitian soldiers playing slide guitar): http://www.ecpad.fr/magazine-n23/ The unit was nicknamed "le bataillon des guitaristes" because, in true Polynesian fashion, there was always someone picking up a guitar...

The Battalion was important in establishing a French Pacific identity and also held the distinction of being a fully racially integrated unit (including French colonists, Polynesians, Melanesians and Asians) at a time when racial segregation was still entrenched in the US Army.

Consequently, my tour this time has its starting point at Bercy, truly one of the ugliest, most soulless parts of Paris, mainly known for being the location of the French Ministry of Finance, but which also features:

Unfortunately it looked like a bomb site when I visited, being in the middle of refurbishment:

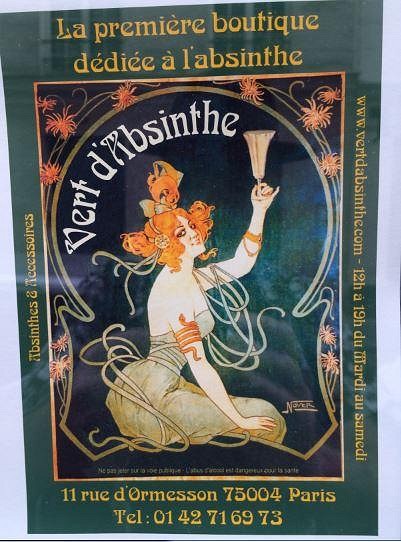

Bercy lies on the banks of the Seine, in Eastern Paris, and is within walking distance of the Place de la Bastille, which is a stone's throw away from Le Marais, featuring an essential stop for absinthe lovers:

This is the place to go if you want authentic French absinthe spoons, among other accessories. Back to Bastille, we head north along the Rue de la Roquette, where, a few blocks along, we find....

La Fée Verte, a French absinthe bar:

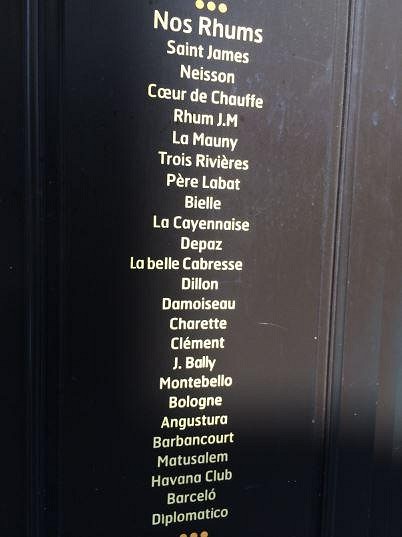

It has more of a mid 20th-century French zinc-lined décor than a Toulouse-Lautrec look about it, but it is authentic. Not far from there, on Rue de Lappe, is a French rum bar worth visiting:

None of yer cocktail menus on the door here mate - they list their rums:

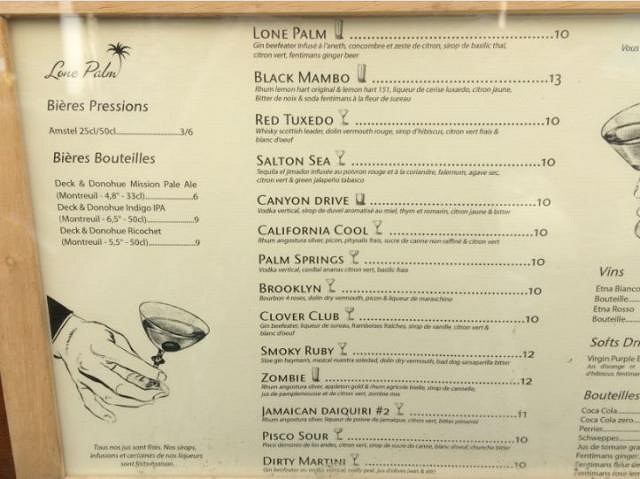

In a very Californian mid-century style is this establishment, in nearby Rue Keller:

Which is just a few doors down from this vintage clothing store, which should not be missed:

This is one of the few places in Paris where you will find real Hawaiian shirts:

And tikis for sale:

Born Bad is a refreshing change from the "vintage" clothing stores around Les Halles/Beaubourg, which seem to consider items from as recently as the 1990s to offer a "vintage' clothing look. But wait, there's more, as we walk further north and on to the depths of the immigrant quarter of Belleville...

But that's for next time, because I have quite a lot to say about this particular establishment. :tiki:

[ Edited by: Club Nouméa 2015-08-14 06:23 ] [ Edited by: Club Nouméa 2015-08-31 02:15 ] |

|

M

MaukaHale

Posted

posted

on

Fri, Aug 14, 2015 11:29 AM

I look forward to your future post about Le Tiki Lounge. In the video they are playing "Steel" guitar which is different than "Slide" guitar. The Hawaiians invented "Steel" guitar that uses a steel bar. Slide guitar is when the guitar is not laid flat and a tube of glass or steel is placed over a finger. |

|

E

EnchantedTikiGoth

Posted

posted

on

Fri, Aug 14, 2015 9:53 PM

This is great! Unfortunately I'm not sure that I would be able to talk my wife into more Tiki-related things when we go back to Paris... That doesn't really fit into her idea of France, and it's enough for me to negotiate going to anything related to Jules Verne :) I'll have to figure out how to do it covertly... "Oh look sweetie, this is some neat store we just accidentally came across, isn't that weird?" |

|

CN

Club Nouméa

Posted

posted

on

Wed, Aug 19, 2015 6:36 AM

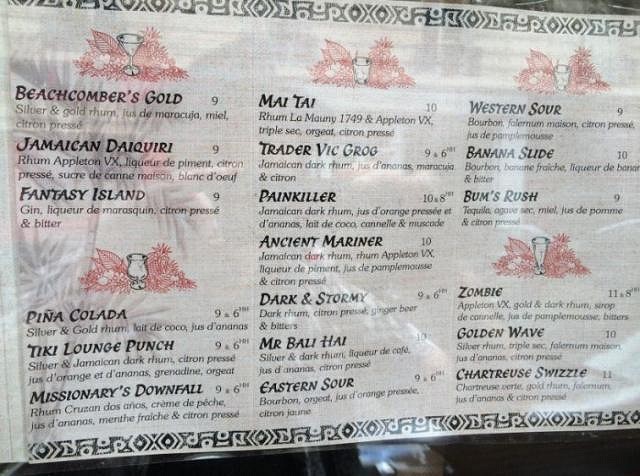

Le Tiki Lounge, Belleville

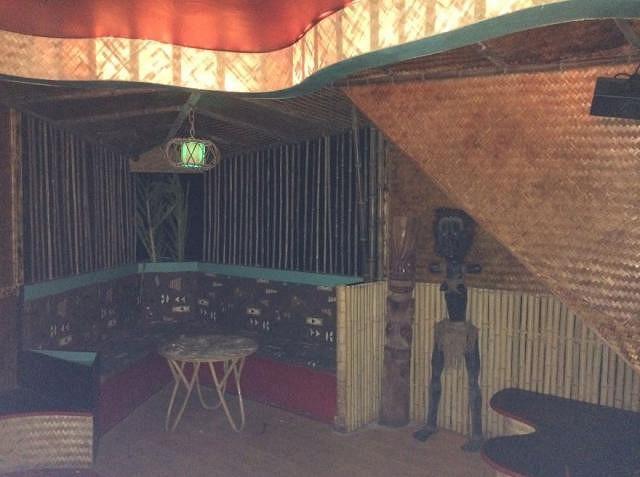

It was my first time back in Belleville in 9 years and my recollection of the place was a bit blurred by time. It is one of Paris's more interesting neighbourhoods, being a traditional bastion of working-class socialism (the last and bloodiest fighting in the Paris Commune of 1871 occurred there), as well as being an immigrant neighbourhood for decades, attracting refugees from the Russian Revolution, Germans fleeing Hitler and, more recently, Maghrebins and Chinese. My last night out in the neighbourhood was in 2006 to see a concert in a seedy basement bar by Dan Penn and Spooner Oldham, but that's another story. This time I was here for the tiki bar, which had popped up a few years ago. Having walked all the way from the Seine, I was parched and was looking somewhat incongruous in spite of my black Hawaiian shirt, as it was only 5 in the afternoon and there was no one there but the owner and the barman. Some confusion ensued over my arrival, as they had only just opened up the place themselves, but a Mai Tai was granted and I settled in, chatting with the owner for a while until a neighbour turned up for a drink. It was her first time there but there turned out to be a South Pacific link - she was in the film business and one of her friends had worked on Mathieu Kassovitz's film "L'ordre et la morale" ("Rebellion" in English), about the Ouvéa hostage incident in New Caledonia in 1988. This prompted my reminiscences about my first visit to New Caledonia shortly after the events in the film, when the place was an armed camp, with Puma military helicopters patrolling continuously overhead, and the morning wake-up call at my hotel being provided by the squealing of military radios being tuned in as a mobile command post in the car park set up for another day's activities. After the neighbour left, the place was still quiet, so I got the opportunity to have a look around and take some photos:

These stairs lead down to a basement:

I was to return several times, later in the evening, when there was more of a crowd, and the atmosphere was always welcoming, to the extent where the place came to feel like a home away from home.

The drinks were very good, while the music was great. Lounge music purists may wince, but the soundtrack of Le Tiki Lounge is 50s and 60s rock and roll. I have been collecting that stuff for over 30 years now but was still only recognising about one in every six or seven of the songs that were being played. It was a welcome change from the usual suspects you tend to hear in retro bars. Various interesting conversations were had with the resident DJs, including one who had been stationed with the Foreign Legion in Tahiti. I took the opportunity to quizz him on various French performers that had always puzzled me: why were these names I kept hearing considered to be so important in the Pantheon of French popular music? To my relief, among other things it was confirmed that Telephone really were just another really bad 80s band and yes, Renaud is naff after all.

The conversation was interesting at the bar and I met all sorts of people. Every night was different.... Topics of discussion ranged far and wide, and were always stimulating.

So I kept coming back, met more people, and even got coaxed out onto the dance floor one night by a couple of lovely Parisian ladies (the one on the right had purloined my hat for that purpose), dancing to the likes of Vince Taylor's "Brand New Cadillac" and The Sorrows' "Take A Heart".

I will always have fond memories of the three Métro station changes from Montparnasse to get to Place de la République, then wending my way through the crowds in that busy square, and walking up the Rue du Faubourg du Temple, ignoring the curious looks at my tapa-patterned South Pacific shirt, all the way from Auckland circa 1970, until I finally got to the one spot in Paris where it did not look out of place: Le Tiki Lounge.

[ Edited by: Club Nouméa 2015-08-19 06:48 ] |

|

CN

Club Nouméa

Posted

posted

on

Sun, Jan 3, 2016 2:08 AM

The First Modern Theme Bar: Tropical Hell at the Taverne du Bagne

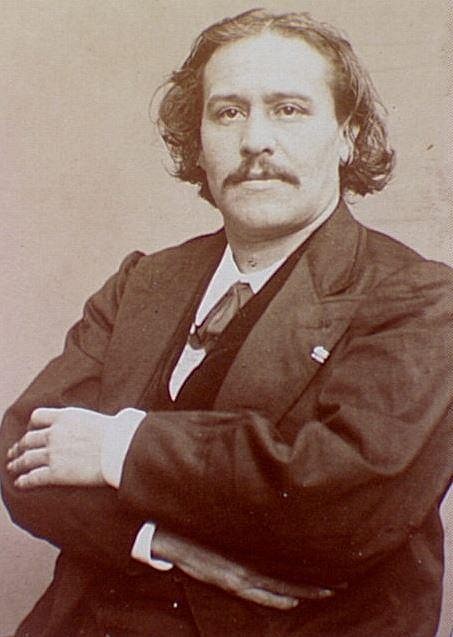

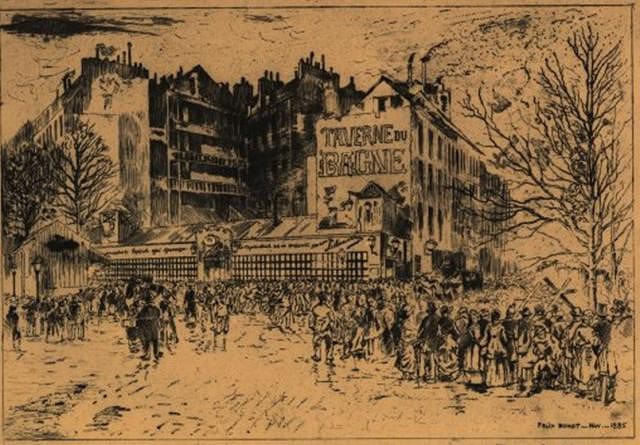

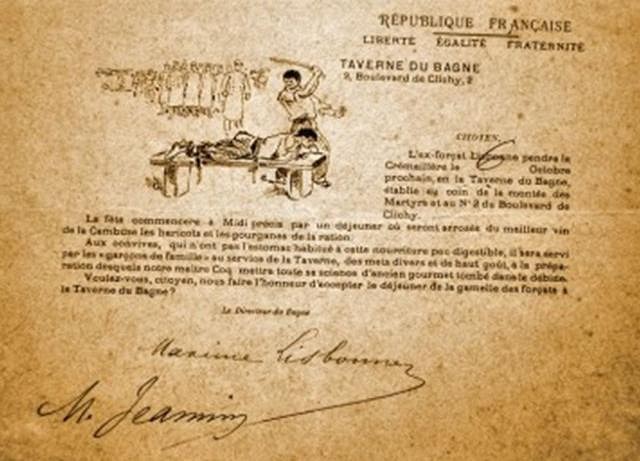

Meet the man who invented the modern South Seas theme bar: Maxime Lisbonne (1839 - 1905). Monsieur Lisbonne was a veteran of the Crimean War who, in the 1860s, became a theatre director in Paris. As a patriotic anarchist with a military background, he sided with the Parisian Communards at the end of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 when France collapsed and the Versailles government negotiated a humiliating peace with the Prussians. For his actions as a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Garde Nationale during the defence of the Paris Commune, in 1871 he was tried and transported to the penal colony of New Caledonia, where he spent the rest of the 1870s, until a general amnesty allowed him and other Communards to return to Paris in 1880. Like various other Communards who had been exiled to penal servitude in New Caledonia, including the anarchist Louise Michel (known as "The Red Virgin"), his return was regarded with some trepidation by the authorities. Louise Michel, for example, was quite unrepentant upon her return and became a thorn in the side of the authorities, speaking out on all manner of social issues. Maxime Lisbonne however, initially returned to a quiet life in the theatre. At least, until 1885, when he came up with his own novel way of getting his own back at the Establishment:

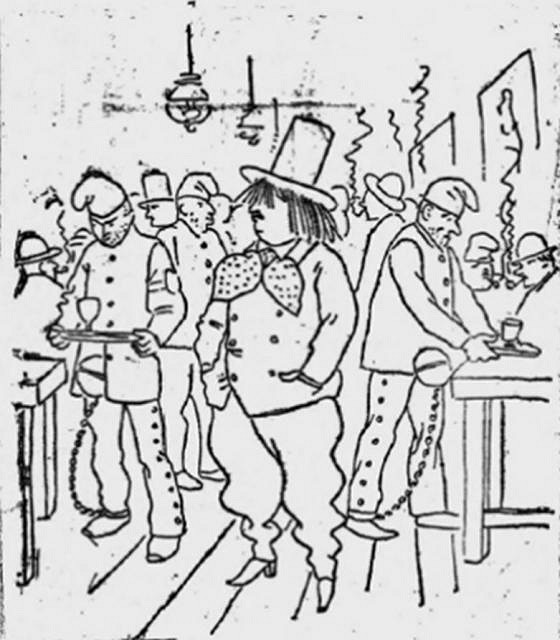

La Taverne du Bagne (The Penitentiary Tavern), at 9 Boulevard de Clichy, on the corner where it meets the Rue des Martyres, is recognised as being the very first modern theme bar, a concept pioneered in Paris in the 1880s. M. Lisbonne drew on both his theatrical background and his experiences in New Caledonia to recreate his own little corner of tropical Hell in Paris. As he doubtless anticipated, the establishment became all the rage for members of the moneyed Parisian middle and upper classes, with queues of people waiting to get in. Each of the customers was greeted individually with a torrent of foul-mouthed abuse from a man dressed as a warder, telling them in no uncertain terms where to sit in the establishment, which offered food as well as drink, and cabaret performers, as well as fiery speeches from Louise Michel and other Communards from time to time. The waiters were decked out in prison garb and carried a ball and chain, although the ball, which they carried hooked over their belt, was hollow and contained a cloth they used to wipe down the tables. The crude rough-timbered interior, designed to replicate the atmosphere of New Caledonian penitentiaries like the Île Nou in Nouméa's harbour, was adorned with large images of various famous Communards and of the sufferings they had endured. M. Lisbonne himself often presided over the preceedings which, as a matter of course, included the ritual humiliation of his well-heeled customers:

Some advertising for the establishment:

As well as providing the conceptual basis for other such establishments in Paris, like the Café-Cabaret L'Enfer (with a trip to Hell being its theme), M. Lisbonne also pioneered the now-common practice of the "consommation obligatoire" (i.e. if you entered the establishment, you had to have at least one drink), presenting each of his customers with a little certificate once they had paid their bills: “RELEASE CERTIFICATE: The prisoner has consumed and was well-behaved. The Director, M. Lisbonne” Spurred on by the roaring financial success that the Taverne du Bagne experienced, M. Lisbonne went on to set up other theme bars and, at an exotic establishment he purchased called the Divan Japonais, presented the very first public strip-tease show in Paris in 1894. Toulouse-Lautrec was a customer there and immortalised the place in his works. So next time you are sitting in your local South Seas-style tiki bar, raise a glass to Maxime Lisbonne. He laid the conceptual groundwork that enabled the likes of Trader Vic's and Don the Beachcomber's to open their doors in the 1930s, although his twist on the South Seas theme was somewhat different from theirs.

[ Edited by: Club Nouméa 2016-01-03 02:20 ] |

|

F

finky099

Posted

posted

on

Tue, Jan 5, 2016 12:57 PM

Club Nouméa, once again your post fascinates me! I have never heard/read of this before, but now I want to know more. The stories this place could tell! Any idea how long these establishments lasted and what the general reaction was from Parisians? Was there a pre-20th century "themed bar/restaurant" trend in Paris (and beyond?)the way mid-century history and value in the US gave rise to the fashion of Polynesian Pop for a while? Cheers and thanks! |

|

CN

Club Nouméa

Posted

posted

on

Tue, Jan 5, 2016 10:54 PM

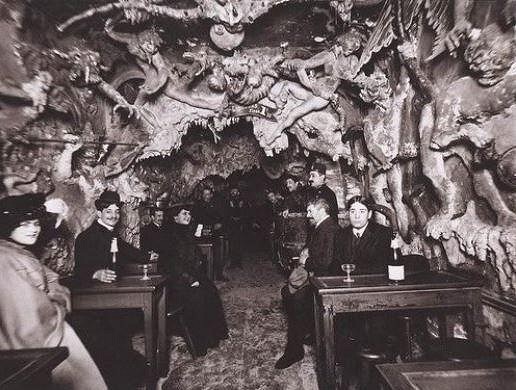

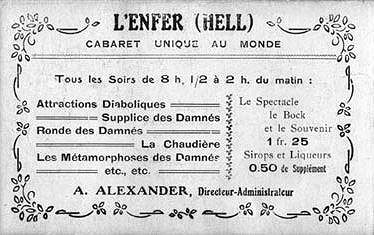

Hello finky099 Maxime Lisbonne is recognised by various historians of French culture as being the starting point for the modern conception of the themed bar. Prior to 1885 yes, you could, for example, walk into places like Irish pubs or Italian cafés in Paris, where they had pictures of the old country on the wall, they served appropriate food and drink, and some or all of the staff may have been Irish, Italian or whatever. The difference with the Taverne du Bagne was that it was that full immersive experience of being transported to another world. You suddenly found yourself in a New Caledonian penitentiary, being treated like a convict. These themed bars, cafés etc. were very popular in Paris in the 1880s and 1890s. All of Parisian high society flocked to the Taverne du Bagne, with aristocrats pulling up in their fancy fiacres etc. Maxime Lisbonne's establishments did not last very long, but the "L'Enfer" cabaret survived until the early 1950s. This place had all the fancy themed trappings that we have come to associate with tiki bars:

An ornate entrance.

A stunning interior!

Themed food and drinks (including syrups and liqueurs) and floorshows, and even a souvenir you could take home with you (I am curious to know what it was). And note the name of the place translated into English for the benefit of their international clientele.... All this should be ringing bells for anyone who has stepped inside a tiki establishment. No it ain't tiki, but it is the same basic concept for drawing customers in by providing them with an exotic or other-worldly experience. L'Enfer survived until the early 1950s but it was very much the exception. Here is an image from circa 1950 that used to be a popular postcard in Paris. You may still find it if you hunt around:

[ Edited by: Club Nouméa 2016-01-05 23:26 ] |

|

F

finky099

Posted

posted

on

Thu, Jan 7, 2016 5:26 PM

Thanks for the additional info and great photos. Almost seems anachronistic thinking about L' Enfer coming into being in the late 1800's and being there until 1950. How cool that there are some photos, too. Cheers! |

Pages: 1 17 replies

"Who's he?" you may very well ask.

"Who's he?" you may very well ask.