Beyond Tiki, Bilge, and Test / Beyond Tiki / Tim Biskup or Shag?

Post #420685 by Cammo on Mon, Nov 24, 2008 6:15 PM

|

C

Cammo

Posted

posted

on

Mon, Nov 24, 2008 6:15 PM

It’s incredibly complicated, but the two artists who seemed to have really started the whole retro design thing were John Kricfalusi and his then-wife Lynne Naylor. They met at Sheridan College and later in 1985 worked on a revival of the Jetsons TV show. Both animators, they shared a burning interest in 1940s thru 1960s animation and design. That was in fact why they had become animators and moved to L.A. – to get involved in what had been the most dynamic art movement of the 20th century, the mid-century marriage of commercial art and design to moving film images and sound. In other words, cartoons. The problem was, it was 1985. That world was long gone. It was gone when they went to work where long line of drones worked on lifeless drawings. It was gone on TV and at the movies. Disney animation was at its lowest creative point in history. Animators were not accepted as illustrators in their spare time, because advertisements were simply not drawn anymore. Nor were they allowed into the ‘fine’ highbrow art world, where depressing collage and abstraction had taken the place of original imagery. John and Lynne had their weekends, though, which they spent hunting down the original animators of the classic age and talking to them as long as either could stand it. Ward Kimball’s place became a hangout. They visited the homes of Disney’s Nine Old Men (or what was left of them) and drank wine with Rolly Crump.

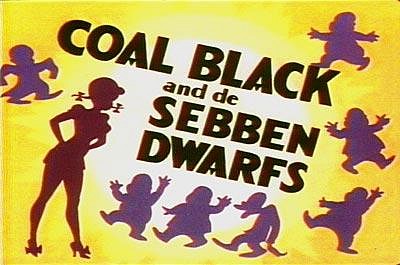

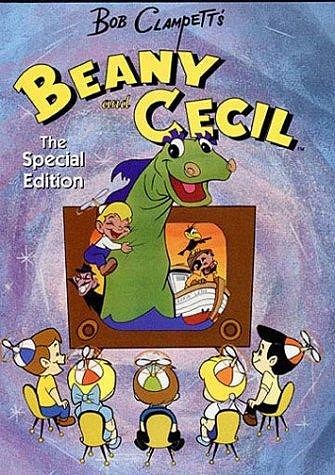

There was a guy John had to meet, though, and he proved to be elusive. Bob Clampett was arguably the wildest artist to ever animate. His long line of work at Warners included the notorious “Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs”, a black Harlem jump-blues version of Snow White, and culminated in the incredible TV show “Beany and Cecil”. I screened B&C for some 14 year olds last year, and they DIDN’T GET IT. Actually, most of their parents didn’t either, they just sat there saying “What is this?” and literally “I don’t get it,” while the funniest puns ever written raced across the backyard projection system. Their response was frightening to me.

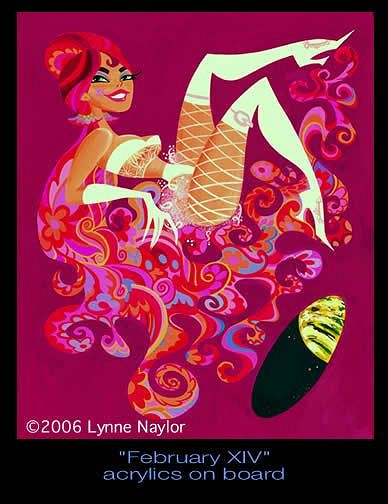

John knew how good Beany and Cecil was, though. Bob Clampett was a creative genius. Bob was getting old, but still wore this jet-black wig and big Cary Grant hipster eyeglasses. John tried calling him, writing to him, even visiting his house, but he never seemed to be home. Maybe he was inside the house, hiding from the way the world had become, not answering the phone or the door. That made John even more furious, that his idol wasn’t appreciated or respected. Clampett, who had more talent in one ear than Disney ever had in his entire body. He’d drive by Clampett’s home, trying to spot him. One day he saw him. There he was coming out the front, heading to his car in the driveway. John screeched to a stop and ran over to him. “Are you Mr. Clampett?” and the whole crowd is waving to them, hundreds of people, all with their hands up, waving back and forth, smiling, laughing, and Clampett turns to Johnny and says “You know, Johnny, I’m not really the Parade Marshall. But this is fun, huh?” And John finally gets it and laughs. He breaks down and hoots, screams, doubles over with laughter. The whole crowd is laughing and smiling too, and there’s Bob and Johnny choked up on that float, trying to drink beer but its spurting out their mouths, they’re laughing so hard. Clampett hadn’t been hiding from the world after all – he had been out every day having fun instead. The whole parade adventure had proven what had become obvious to John and Lynne and their small but growing circle of animator friends – that the older generation had been wild living, incredibly fun party monsters. Stories were told of how Fred Moore had fallen out of a window in 1942, (or was it 1944?) but was too drunk to get hurt, or how Preston Blair ran a 24 hour party 7 days a week out of his fashionable beatnik home, or how it had always been easy to find Ward on the Disney lot by just listening for the Dixieland Jazz pumping at full volume from his new stereo set. The best legends of all regarded the Disney trip to South America in 1941, where Walt paid his senior design staff to go on a giant holiday in South America, sketching and partying with the locals for ten weeks on end. The result was the incredible cartoon “The Three Cabalaros”, possibly the best thing the studio ever did, and the kick-start ignition for Mary Blair’s revolutionary graphic design work to follow. Where had all the fun gone? Well, one place it had gone was into Lynne’s drawing pad. She was on fire in the late 80s, examining old commercial ads and VHS tapes, sketching, making up characters like crazy, creativity gushing out of her pencil like Niagara Falls, colors in every hue next to each other, inside each other, line, marker and gouache work like nothing anybody had ever seen before, developing a style that was both obviously retro and 60’s space-age futuristic at the same time, sexy and immaculate in conception and form. She’d sell some of these sketches to people at work, and everybody told her she should have a gallery show, but no gallery in the nation would touch her because she was a cartoon artist and thus didn’t know what she was doing.

So now it was more and more horrible for John and Lynne to go back to working on the projects they were told to draw. John kept wondering “What Would Bob Do?” and started pitching story and show ideas to anybody who would listen. Lynne would draw the characters in a crazy 50s-on-drugs style, and finally somebody at the new Nickelodeon Network listened to them and started asking questions about their drawings of an angry drunk and a retarded kid with the two pets called Ren and Stimpy. It was always designed as a retro show, right from the start in 1989. John’s idea was to do the show as three 7.5 minute cartoons, just like Bugs Bunny’s. It was a simple idea, and would work perfectly with the two commercial breaks: Opening Bizarrely, this was the one thing the Network was against from the start. It was never explained why. They wanted two 11 minute cartoons per show, and that was that. After promising to never do anything funny in the show, and draw the characters in a wavy line R.O. Blechman style then popular in NY illustration, and never have the characters actually go anywhere (they had to stay in their yard) John proceeded to do exactly the opposite. The network couldn’t do anything about it, because they had already paid for the show. They HAD to accept the results. Ren & Stimpy not only had 50’s style character design, but it was edited in the milk-the-laughs style of early 1960s TV cartoons, it jumped off character if it was funnier that way, it used corny canned 50’s music, it used opaque gouache backgrounds, it cut to detailed paintings to make a point – all retro, all excellent, totally different than what people were used to seeing. And it changed everything. Most of the retro designers and animators we know of now came from John and Lynne’s camp; Tim Biskup and Seonna Hong, Miles Thompson were gouache animation background artists after Lynne’s influence became an industry standard; Ren & Stimpy’s Chris Reccardi is Lynne’s husband now. Chris Reccardi: Finally, here’s John Kricfalusi, and listen to how impassioned he still is; “You meet young artists now and try to teach them something and they say, 'I could do it that way if I wanted to, but this is my style. I draw club feet because it's my style.' Unfortunately, schools are really bad now. Schools are not only bad in reading, writing and arithmetic, they're worse in cultural aspects, like in music and art. They don't teach you anything anymore. I know this from twenty years of experience hiring artists out of the schools. They get worse every year. They're absolutely ridiculously retarded now. They don't teach you anything and the few things that they try to teach you are completely wrong. They don't teach you construction, line of action, nothing. Illustration from the late-1900s up through the middle of the 20th century was absolutely amazing. In general, American culture was at its highest skill wise in every aspect of human life in the 1940s. It's all been downhill since then. You just open an old magazine from the 1930s and '40s and look at the illustrations in it. There's nobody alive that could touch the way they could draw back then. In old movies, the cinematography is a thousand times better than anything today. Writing, a thousand times better. The standards in the 1940s were extremely high in all aspects of American culture. And they had schools that were like boot camp. They made you learn things. You couldn't walk into a school and say, 'Well, it's my style to draw badly.' You wouldn't get into the school. You'd have to be pretty damn good before you came to the school and then once you get there, they were extremely strict about your learning every technical aspect of art. Not only the obvious things like life drawing, anatomy, perspective, but elusive hard to teach concepts like composition and color theory. You buy any book on color theory today and it's just complete poppy cock. Everybody comes out of school painting pink, purple and green. The whole damn cartoon industry has pink purple and green on their mind.” [ Edited by: Cammo 2008-11-24 18:24 ] |