Tiki Central / General Tiki / Man Ray, the Surrealists, and African/Pacific culture

Post #503571 by ikitnrev on Mon, Jan 11, 2010 12:05 PM

|

I

ikitnrev

Posted

posted

on

Mon, Jan 11, 2010 12:05 PM

I just discovered the Washington Post review of the above Man Ray show, written by Blake Gobnick. He has some interesting views of how different groups of people can intrepret artwork differently, so I've decided to post the entire review here ...... At the Phillips, Black and White but Never Plain

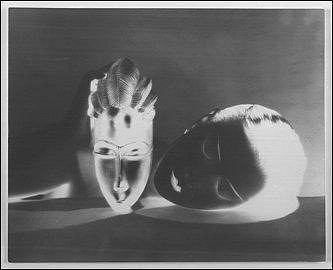

That is the strange situation on view in "Man Ray, African Art and the Modernist Lens," a fascinating new exhibition at the Phillips Collection. You don't have to care about African art or modernist photography to want to delve into their unlikely intersection. The Phillips show presents about 50 images by such pioneers of "straight" modernist photography as Alfred Stieglitz, Walker Evans and Charles Sheeler. It also includes about the same number by Man Ray, one of photography's more radical figures. Born in Brooklyn in 1890 as Emmanuel Radnitsky, he moved to Paris in 1921 and made his (new) name as one of the first surrealist photographers, adding a dose of strangeness to the photos seen in both museums and the fashion world. Photographs by all these figures helped African art filter deep into the consciousness of Western culture. The exhibition also displays many of the actual African objects shown in the photographs. Those objects seem to stand in for their African makers, whose art was being grabbed to use for European ends. "Grab" is the right word, because ever since the 1890s the so-called "scramble for Africa" had gotten Europeans grabbing all but fragments of the continent as theirs. The exhibition includes a map of Africa colored to show the colonial holdings of England, France, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Italy and even little Belgium -- with almost nothing not colored in, that is. The map tells a chilling back story to the art on view. One reading of the Western taste for African art is that it's another way for the West to assert its power -- that African sculptures serve, at least unconsciously, as trophies of war. Many of the photos in this show were commissioned by collectors eager to document the foreign objects they'd amassed. Boldly lit and isolated against plain backgrounds -- which means they're also isolated from the cultures they came out of -- the African artifacts are easily seen as colonial booty. Other photos document commercial dealers' shows, with the African art taking on the role of yet another "natural" resource drained from the colonies and injected into the Western economy. One early photo at the Phillips was taken by Stieglitz himself, to document his 1914 exhibition of African works borrowed from a French dealer hunting for new markets in the United States. That's one reading, as I said, and it has its strengths, in social and political terms. But it goes against a lot of what the art world seemed to feel at the time. One reason African art seemed so appealing to the avant-garde was that the glories of Western "advancement" had, after all, led to the useless slaughter of World War I. If the "advanced" was a dead end, maybe the "primitive" could offer a new model. Viewed as a cultural blank slate, uprooted African art could be used to mean almost anything the West wanted it to. African art could be nobly savage, showing mankind in a state of uncorrupted grace. That seems to be the import of a Stieglitz shot of Georgia O'Keeffe, topless and Eve-like as she contemplates an African spoon. It's a reading that particularly appealed to the thinkers of the Harlem Renaissance, as they sought to find a "noble" past stolen from them by ignoble slavery. Wendy Grossman, the freelance curator who spent decades working on the objects and issues in this show, has done a particularly good job underscoring the complex relationship between Africa and African America. On another reading, African art could be dark and numinous, revealing the glorious terrors of the pre-civilized mind. That was a different option Harlem could take up, in its more radical moods. As painter Aaron Douglas said in 1925, "I want to be frightful to look at. A veritable black terror." By 1936, when the British surrealist Roland Penrose photographs two white men wearing African masks, it's clear he thinks of those masks as representing pure Freudian id. Many of this show's photographs by Man Ray himself seem to buy into that view. He was, after all, another card-carrying surrealist, so even when he was paid just to document some rich person's collection, he would surround each African object with a chaos of shadows. He also chose lenses and camera angles that would make his African "spirits" look huge and looming, when the original objects are most often small and unassuming. And Man Ray liked to boost his sculptures' terror quotient with the harshest of theatrical lights, so that they look almost lightning-struck. You wonder if that's one source for all the Halloween spotlighting that's still the norm in some museums' African departments. (Last I checked, there were no spotlights in the African villages these objects came out of.) Others could read African art as unusually crisp and bold, a close cousin to the machine parts that influenced much modernist sculpture. Installation shots from the landmark "African Negro Art" exhibition, held in 1935 at the Museum of Modern Art, show generously spaced objects on geometrical white plinths against plain white walls under soft daylight. MoMA hired the great Walker Evans to document the exhibition, so its influence could spread beyond the reach of the objects themselves. Evans's crisp, modernist shots are some of the most attractive objects in this show -- partly because they seem to leave the sculptures they depict unchanged and unannotated. If there's one surprise in this whole exhibition, it's how many of the Western photos come off as weaker than the foreign objects they depict. Those beg you to try to come to grips with them on their own terms, whatever you guess those might be, rather than through the filters of Western modern art. Only one of the photographs on view can easily compete: Man Ray's iconic "Noire et blanche" from 1926 -- not simply "Black and White," as the title is sometimes translated, but specifically "Black Woman and White Woman." It is a beautiful shot, even in purely formal terms: The perfect white oval of one face, at a right angle to another that is black. But what seems to make it really work is that it digs into racial issues that stay buried in many of this show's other photographs. Man Ray even printed an alternative version of it as a photographic negative, with the white face as black and the black as white. The world of race could be different than it is, that image seems to say. Too bad for Africa it wasn't. * I've located an image of the 'alternative negative' photo mentioned in the last paragraph .... here it is.

[ Edited by: ikitnrev 2010-01-11 12:11 ] |