Pages: 1 8 replies

|

I

ikitnrev

Posted

posted

on

Mon, Jan 11, 2010 11:56 AM

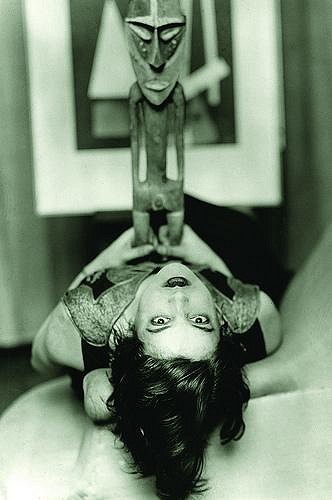

Yesterday I attended a art exhibit at the Phillips Museum in Washington D.C., titled "Man Ray, African Art, and the Modernist Lens" which showed how Man Ray and other prominent art photographers of the 1920's and 1930's incorporated African art and artifacts into their works. It was quite interesting for me, as it provided another piece of the jigsaw puzzle of how non-Western art was exposed and became more acceptable to the general U.S. public. Here is one of Man Ray's more famous photographs from the show, 'Noire et blanche'..... Although the show did focus on African art, there was at least one art item from the Pacific included. Here is a Man Ray photograph of Simone Kahn, posing with a sculpture from Vanuatu (located in the Pacific Malekula Islands)

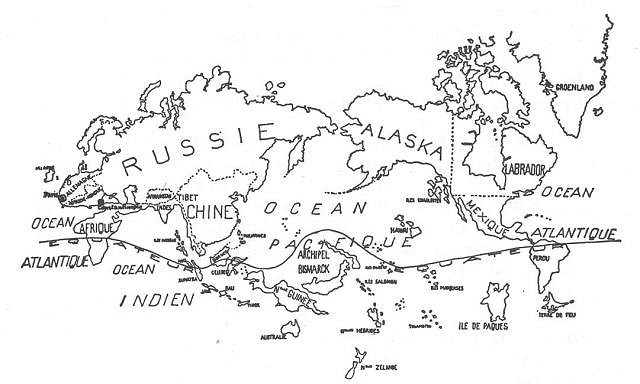

The promotional video for the show gives one a fairly good idea of what the show was about - I see definite common ground between the African art shown in this clip, and the wall displays and carvings in several tiki rooms I have seen. (at the 34 second mark, you see a closeup of a African drinking mug - precursor to a tiki mug?) The show also discussed the linkages between the surrealists and Pacific culture. After the devastation of World War I, the surrealists, in a form of protest, shifted much of their attention and focus to the more 'pure' cultures of the world, which were untouched by economic greed, colonialism, or massive displays of firepower. One item on display at the Man Ray show was this world map, showing a Surrealist View of the World - this was published in June 1929, in the Belgium Surrealist magazine 'Varietes'

This map was drawn after a period when the African zeitgeist had been a part of the Art World for several years (think of dancer Josephine Baker in Paris in the late 1920's.) There was a shift of emphasis of some from Africa to the Pacific, partly because the surrealists, with the need to be on the leading edge away from the mainstream, simply considered African art to be so 'yesterday.' It is somewhat ironic that the avant-garde surrealists, in protest to WW1, shifted their personal influences to the Pacific area in the 1920's and 30's. Yet it was WW2, and the after-effects of the large number of U.S. servicemen returning from the Pacific Islands, that played a larger factor in influencing the general U.S. population of Pacific cultural artificacts. The Man Ray show in D.C. ended yesterday - it will travel later this year to Albuquerque, Vancouver, and Charlottesville, Va. I quick flipped through the catalog, and was impressed enough to purchase it. Priced at $30 on amazon, it is a welcome addition to my personal library section. http://www.amazon.com/Man-Ray-African-Modernist-Lens/dp/081667017X Vern |

|

I

ikitnrev

Posted

posted

on

Mon, Jan 11, 2010 12:05 PM

I just discovered the Washington Post review of the above Man Ray show, written by Blake Gobnick. He has some interesting views of how different groups of people can intrepret artwork differently, so I've decided to post the entire review here ...... At the Phillips, Black and White but Never Plain

That is the strange situation on view in "Man Ray, African Art and the Modernist Lens," a fascinating new exhibition at the Phillips Collection. You don't have to care about African art or modernist photography to want to delve into their unlikely intersection. The Phillips show presents about 50 images by such pioneers of "straight" modernist photography as Alfred Stieglitz, Walker Evans and Charles Sheeler. It also includes about the same number by Man Ray, one of photography's more radical figures. Born in Brooklyn in 1890 as Emmanuel Radnitsky, he moved to Paris in 1921 and made his (new) name as one of the first surrealist photographers, adding a dose of strangeness to the photos seen in both museums and the fashion world. Photographs by all these figures helped African art filter deep into the consciousness of Western culture. The exhibition also displays many of the actual African objects shown in the photographs. Those objects seem to stand in for their African makers, whose art was being grabbed to use for European ends. "Grab" is the right word, because ever since the 1890s the so-called "scramble for Africa" had gotten Europeans grabbing all but fragments of the continent as theirs. The exhibition includes a map of Africa colored to show the colonial holdings of England, France, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Italy and even little Belgium -- with almost nothing not colored in, that is. The map tells a chilling back story to the art on view. One reading of the Western taste for African art is that it's another way for the West to assert its power -- that African sculptures serve, at least unconsciously, as trophies of war. Many of the photos in this show were commissioned by collectors eager to document the foreign objects they'd amassed. Boldly lit and isolated against plain backgrounds -- which means they're also isolated from the cultures they came out of -- the African artifacts are easily seen as colonial booty. Other photos document commercial dealers' shows, with the African art taking on the role of yet another "natural" resource drained from the colonies and injected into the Western economy. One early photo at the Phillips was taken by Stieglitz himself, to document his 1914 exhibition of African works borrowed from a French dealer hunting for new markets in the United States. That's one reading, as I said, and it has its strengths, in social and political terms. But it goes against a lot of what the art world seemed to feel at the time. One reason African art seemed so appealing to the avant-garde was that the glories of Western "advancement" had, after all, led to the useless slaughter of World War I. If the "advanced" was a dead end, maybe the "primitive" could offer a new model. Viewed as a cultural blank slate, uprooted African art could be used to mean almost anything the West wanted it to. African art could be nobly savage, showing mankind in a state of uncorrupted grace. That seems to be the import of a Stieglitz shot of Georgia O'Keeffe, topless and Eve-like as she contemplates an African spoon. It's a reading that particularly appealed to the thinkers of the Harlem Renaissance, as they sought to find a "noble" past stolen from them by ignoble slavery. Wendy Grossman, the freelance curator who spent decades working on the objects and issues in this show, has done a particularly good job underscoring the complex relationship between Africa and African America. On another reading, African art could be dark and numinous, revealing the glorious terrors of the pre-civilized mind. That was a different option Harlem could take up, in its more radical moods. As painter Aaron Douglas said in 1925, "I want to be frightful to look at. A veritable black terror." By 1936, when the British surrealist Roland Penrose photographs two white men wearing African masks, it's clear he thinks of those masks as representing pure Freudian id. Many of this show's photographs by Man Ray himself seem to buy into that view. He was, after all, another card-carrying surrealist, so even when he was paid just to document some rich person's collection, he would surround each African object with a chaos of shadows. He also chose lenses and camera angles that would make his African "spirits" look huge and looming, when the original objects are most often small and unassuming. And Man Ray liked to boost his sculptures' terror quotient with the harshest of theatrical lights, so that they look almost lightning-struck. You wonder if that's one source for all the Halloween spotlighting that's still the norm in some museums' African departments. (Last I checked, there were no spotlights in the African villages these objects came out of.) Others could read African art as unusually crisp and bold, a close cousin to the machine parts that influenced much modernist sculpture. Installation shots from the landmark "African Negro Art" exhibition, held in 1935 at the Museum of Modern Art, show generously spaced objects on geometrical white plinths against plain white walls under soft daylight. MoMA hired the great Walker Evans to document the exhibition, so its influence could spread beyond the reach of the objects themselves. Evans's crisp, modernist shots are some of the most attractive objects in this show -- partly because they seem to leave the sculptures they depict unchanged and unannotated. If there's one surprise in this whole exhibition, it's how many of the Western photos come off as weaker than the foreign objects they depict. Those beg you to try to come to grips with them on their own terms, whatever you guess those might be, rather than through the filters of Western modern art. Only one of the photographs on view can easily compete: Man Ray's iconic "Noire et blanche" from 1926 -- not simply "Black and White," as the title is sometimes translated, but specifically "Black Woman and White Woman." It is a beautiful shot, even in purely formal terms: The perfect white oval of one face, at a right angle to another that is black. But what seems to make it really work is that it digs into racial issues that stay buried in many of this show's other photographs. Man Ray even printed an alternative version of it as a photographic negative, with the white face as black and the black as white. The world of race could be different than it is, that image seems to say. Too bad for Africa it wasn't. * I've located an image of the 'alternative negative' photo mentioned in the last paragraph .... here it is.

[ Edited by: ikitnrev 2010-01-11 12:11 ] |

|

B

bigbrotiki

Posted

posted

on

Mon, Jan 11, 2010 6:26 PM

Wow, sounds like a great show!

It is nice to see that some of my favorite subjects which I could only touch on in TIKI MODERN are now being researched and dealt with more in depth. Tiki Modern, Chapter 2: ..... Another young avant-garde group that found their cause supported by the unusual artworks from Oceania were the Surrealists. The 1926 opening exhibition of the Galerie Surrealiste in Paris featured not only the contemporary works of Man Ray,but also a selection of authentic Oceanic objects from the collections of Andre Breton, Louis Aragon and others. Ordered the book, thanks Vern. You do own that "piece of the jigsaw puzzle" called Tiki Modern, don't you, Vern? :) |

|

I

ikitnrev

Posted

posted

on

Mon, Jan 11, 2010 8:48 PM

I knew I had seen that Man Ray image somewhere before, and I suspected that it might have been in one of Sven's books. I was just too lazy :) to confirm this before I wrote the above post. I knew something had to be the cause of my own personal push to see the Man Ray exhibit before it closed. I discovered a blog that provides some further mentions of the connection between Oceania and surrealism ...... just scroll down the list, and various items will pop up. http://www.socialfiction.org/index.php?tag=surrealism Vern |

|

B

bigbrotiki

Posted

posted

on

Mon, Jan 11, 2010 11:39 PM

Oh good, for a moment there I really thought you would be Tiki Mod-less. http://www.tikicentral.com/viewtopic.php?topic=34682&forum=12&vpost=501094 I really appreciate your posts, Vern, they are rare, but when you do post, it has real content. |

|

Z

Zeta

Posted

posted

on

Wed, Jan 13, 2010 3:41 PM

I love that surrealist map of the world, or: "Le monde au temps des surrealistes" I was going to post about it 3 days ago... Those crazy artists... |

|

Z

Zeta

Posted

posted

on

Wed, Apr 7, 2010 6:53 AM

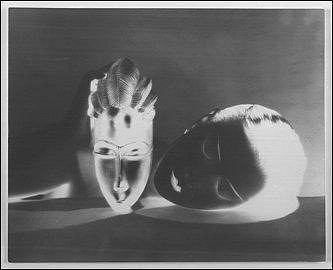

From the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston: |

|

W

wagross

Posted

posted

on

Fri, Sep 24, 2010 7:23 PM

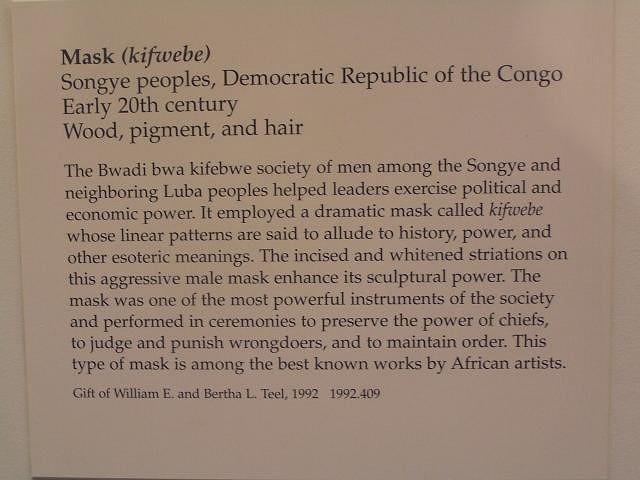

In reply to the previous poster's query about the location of the surrealist photograph in which a Songye mask like the one pictured from the BMA appears, it is included in the Man Ray exhibition discussed above and illustrated in the accompanying catalogue. The second mask is from Papua New Guinea. See attached. It was taken by the British surrealist artist Roland Penrose at the time of the 1937 surrealist exhibition in London. Penrose's son believes that the two men behind the masks are the French and Belgian surrealist writers Paul Eluard and E.L.T. Mesens. Comments about the exhibition are appreciated (I'm the curator). Please add your comments to the reviews on Amazon, if you are so inclined.

|

|

B

bigbrotiki

Posted

posted

on

Fri, Sep 24, 2010 9:25 PM

How funny, another photo I also put in Tiki Modern. It is uncanny how certain things just pop up at the same time. I just put this review for the book up on Amazon: "This book is more proof that there is a current Zeitgeist which wants to shed more light on the relationship between "primitive" art and the moderns, a phenomenon that had been forgotten and marginalized for too long. It is difficult to assess today what an impact the native arts of Africa and Oceania had on artists in the early 20th Century, and how and why they could use these esthetic concepts as inspiration and as subversive tools to rock the Status Quo, but this book admirably enlightens and broadens the view on this important step in the evolution of modern art." |

Pages: 1 8 replies