Pages: 1 8 replies

|

C

christiki295

Posted

posted

on

Tue, Jun 5, 2007 8:44 PM

Polynesians beat Spaniards to South America, study shows June 5, 2007 After decades of contention, New Zealand researchers have provided the first direct evidence that Polynesians sailed across thousands of miles of the Pacific Ocean to reach South America long before the arrival of the Spanish around AD 1500. Their proof? Chicken bones. Using genetic analysis and radiocarbon dating of chicken bones found in Chile, the researchers showed that the fowl originated in Polynesia, not Europe as was previously believed, the researchers said Monday. "The Polynesian contact probably didn't change the course of prehistory, but I think maybe it makes us recognize the ethnocentrism in our long-standing views of the prehistory of the New World," said archeologist Terry L. Jones of Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, who was not involved in the research. "The basic premise has always been that there was only one civilization capable of crossing the ocean and discovering the New World," he said. The new findings, reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, indicate that "the prehistory of the New World was probably a little bit more complicated than we thought in the past." The possibility of contact between Polynesia and the New World has been a subject of contention since Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl's famous 1947 voyage aboard his crude raft Kon-Tiki. Heyerdahl believed that an ancient, fair-haired race originating high in the Andes around Lake Titicaca sailed to the Pacific islands. He attempted to prove his ideas by setting off on a trip from the west coast of South America on a raft based on Inca designs. The 4,300-mile trip from Peru to the Tuamotu Islands took 101 days, but subsequent trips were much faster once researchers learned how to steer the boats. Despite Heyerdahl's demonstration, the idea that Polynesians could have routinely — or even occasionally — navigated across the Pacific was considered farfetched, primarily because of the lack of proof. "Scientists have not been willing to fully accept the idea" of prehistoric contact between Polynesia and South America, Jones said, "but it is hard to understand why." The most convincing previous evidence of cultural contact was the presence of sweet potatoes — a native American plant — at archeological sites throughout Polynesia. Most notably, sweet potatoes dating from about AD 1000 have been found on the Cook Islands. Equally important, Jones noted, the name of the potato used throughout Polynesia is the same name given it by South Americans. Heyerdahl's trip and the discovery of the sweet potatoes showed South Americans could have taken the sweet potato to the islands but did not demonstrate that the islanders could have come to South America. The new findings show that definitively, said the senior author of the new report, archeologist Elizabeth A. Matisoo-Smith of the University of Auckland. The chicken bones were recovered from a site called El Arenal-1 in south-central Chile, about a mile and a half inland on the southern side of the Arauco Peninsula. Thermoluminescent dating of ceramics from the site indicates it was occupied from AD 700 to 1390. Analysis of the bones was conducted by graduate student Alice A. Story in Matisoo-Smith's lab. Matisoo-Smith said she didn't expect much from the study because finding evidence of Polynesian contact would be like "finding a needle in a haystack." But radiocarbon dating showed the bones were about 622 years old. Even with potential errors, they dated from AD 1321 to 1407 — before Spaniards first trod the New World. Genetic analysis of the chickens showed that they were identical to genetic sequences of chicken from that same time period in American Samoa and Tonga, both more than 5,000 miles from Chile. The sequences were very similar to those of chickens from Hawaii, also about 5,000 miles distant, and Easter Island, about 2,500 miles away. "I was pretty excited when the dates came back as clearly pre-European," Matisoo-Smith said. "There were no questions. The Europeans didn't pick them up in Polynesia and bring them back" to South America, she said. Sailing into the wind from the islands to South America "requires significant sailing technology and navigational skills," she said. "But if you look at the winds, leaving from Easter Island, you would actually land [in South America] around the area where El Arenal-1 is located. You could then make the return voyage further north." Jones of Cal Poly is particularly pleased because the find supports his theory that Polynesians also landed in the Northern Hemisphere. He and linguist Kathryn A. Klar of UC Berkeley have argued that the Chumash Indians of Southern California learned to build their sewn-plank canoes from the Polynesians, in part because the names of the ships are very similar in the two unrelated languages. Composite bone fishhooks used by the Indians also closely resembled those used in Polynesia. If we know they landed in Chile, he said, "then why is it so difficult to imagine they couldn't have made it to Southern California from Hawaii?" |

|

C

christiki295

Posted

posted

on

Tue, Jun 5, 2007 9:22 PM

My Bad - Double post: http://www.tikicentral.com/viewtopic.php?topic=24353&forum=1&2 |

|

K

Kaiwaza

Posted

posted

on

Tue, Jun 5, 2007 10:40 PM

It just goes to show you what we KNEW all along..Sweet And Sour Chicken is POLYNESIAN!! |

|

K

Koolau

Posted

posted

on

Wed, Jun 6, 2007 12:17 AM

Very interesting - it only makes sense, seeing how successful and wide ranging the Polynesians were in their big voyaging canoes. But, like the independent Mayan discovery of mathematical zero, it's a neat bit of trivia that essentially has no impact on the history of the world. |

|

B

bigbrotiki

Posted

posted

on

Wed, Jun 6, 2007 1:08 AM

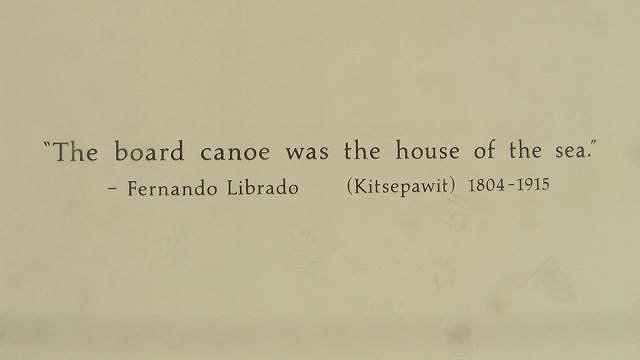

Splendid! The Chumash connection clearly proves an early cause and effect of why California became the birthplace of Polynesian pop: |

|

S

Sneakytiki

Posted

posted

on

Wed, Jun 6, 2007 1:08 AM

No doubt the Polynesians made landings and intrusions in numerous locations on the Western American coasts. There is pretty good evidence for Melanesians in South America and even Neanderthal type skeletons previously unseen elsewhere. The Solutrean Hypothesis and DNA testing, blood haplotypes, etc. show that early Europeans likely made land on the East coast of N. America. Cool stuff for sure. But none of it proves Heyerdahl was right about anything except for diffusionist theory, ie. people have traveled great distances/interacted for some time. That said, excellent info! Thanks for posting. PS ST To drown sorrow, where should one jump first and best? "Certainly not water. Water rusts you." -Frank Sinatra [ Edited by: Sneakytiki 2007-06-06 18:26 ] |

|

O

Ojaitimo

Posted

posted

on

Mon, Jun 11, 2007 11:20 AM

From the Chumash web site http://www.santaynezchumash.org/ Our people once numbered in the tens of thousands and lived along the coast of California. At one time, our territory encompassed 7,000 square miles that spanned from the beaches of Malibu to Paso Robles. The tribe also inhabited inland to the western edge of the San Joaquin Valley. We called ourselves “the first people,” and pointed to the Pacific Ocean as our first home. Many elders today say that Chumash means “bead maker” or “seashell people.” The Chumash Indians were able to enjoy a more prosperous environment than most other tribes in California because we had resources from both the land and the sea. As hunters, gatherers, and fishermen, our Chumash ancestors recognized their dependency on the world around them. Ceremonies soon came to mark the significant seasons that their lives were contingent upon with emphasis given to the full harvest and the storage of food for the winter months. During the winter solstice, the shaman priests led several days of feasting and dancing to honor the power of their father, the Sun. Our Chumash ancestors lived in large, dome-shaped homes that were made of willow branches. Whalebone was used for reinforcing and the roofs were composed of tulle mats. The interior rooms were partitioned for privacy by hanging reed mats from the ceiling. As many as 50 people could live in one house. With platform beds built above the ground, the Chumash used the area under the platforms to store personal belongings. Our people distinguished themselves as the finest boat builders among the California Indians. Pulling the fallen Northern California redwood trunks and pieces of driftwood from the Santa Barbara Bay, our Chumash ancestors soon learned to seal the cracks between the boards of the large wooden plank canoes using the natural resource of tar. This unique and innovative form of transportation allowed them access to the scattered Chumash villages up and down the coastline and on the Channel Islands. As the Chumash culture advanced with basketry, stone cookware, and the ability to harvest and store food, the villages became more permanent. The Chumash society became tiered and ranged from manual laborers to the skilled crafters, to the chiefs, and to the shaman priests. Women could serve equally as chiefs and priests. Chieftains, known as wots, were usually the richest, and, therefore, the most powerful. It was not uncommon for one chief to hold responsibility for several villages. The son or daughter could inherit this position of authority for the Chumash community when the chief died. The Chumash villages were endowed with a shaman/astrologer. These gifted astronomers charted the heavens and then allowed the astrologers to interpret and help guide the people. The Chumash believed that the world was in a constant state of change, so decisions in the villages were made only after consulting the charts. In the rolling hills of the coastline, our Chumash ancestors found caves to use for sacred religious ceremonies. The earliest Chumash Indians used charcoal for their drawings, but as our culture evolved, our ancestors colorfully decorated the caves using, red, orange, and yellow pigments. These colorful yet simple cave paintings included human figures and animal life. They used a technique of applying dots around the figures to make them more distinct. Many of the caves still exist today, protected by the National Parks system, and illustrate the spiritual bond the Chumash hold with our environment. As with most Native American tribes, the Chumash history was passed down from generation to generation through stories and legends. Many of these stories were lost when the Chumash Indian population was all but decimated in the 1700s and 1800s by the Spanish mission system. Development of Missions and the Central Coast The modern day towns of Santa Barbara, Montecito, Summerland, and Carpinteria were carved out of the old Chumash territory. The town of Santa Barbara began with Spanish soldiers who were granted small parcels of land by their commanders upon retiring from military service. After mission secularization in 1834, lands formerly under mission control were given to Spanish families loyal to the Mexican government. Meanwhile, other large tracts were sold or given to prominent individuals as land grants. Mexican authorities failed to live up to their promises of distributing the remaining land among the surviving Chumash, causing further decline in the Chumash population. By 1870, the region’s now dominant Anglo culture had begun to prosper economically. The Santa Barbara area established itself as a mecca for health seekers, and by the turn of the century it became a haven for wealthy tourists and movie stars. Around 1880, the region began to establish itself as an important hub of agriculture and horticulture. Most of the Chumash who remained in the area survived through menial work on area farms and ranches. [ Edited by: Ojaitimo 2007-06-11 17:43 ] |

|

SM

Scott McGerik

Posted

posted

on

Mon, Jun 11, 2007 2:12 PM

NewScientist.com has a similar article on the subject at http://www.newscientist.com/article.ns?id=dn11987. Polynesians beat Columbus to the Americas

Prehistoric Polynesians beat Europeans to the Americas, according to a new analysis of chicken bones. The work provides the first firm evidence that ancient Polynesians voyaged as far as South America, and also strongly suggests that they were responsible for the introduction of chickens to the continent - a question that has been hotly debated for more than 30 years. Chilean archaeologists working at the site of El Arenal-1, on the Arauco Peninsula in south-central Chile, discovered what they thought might be the first prehistoric chicken bones unearthed in the Americas. They asked Elizabeth Matisoo-Smith at the University of Auckland, New Zealand, and colleagues to investigate. The group carbon-dated the bones and their DNA was analysed. The 50 chicken bones from at least five individual birds date from between 1321 and 1407 - 100 years or more before the arrival of Europeans. However, this date range does coincide with dates for the colonization of the easternmost islands of Polynesia, including Pitcairn and Easter Island. And when the El Arenal chicken DNA was compared with chicken DNA from archaeological sites in Polynesia, the researchers found an identical match with prehistoric samples from Tonga and American Samoa, and a near identical match from Easter Island. Easter Island is in eastern Polynesia, and so is a more likely launch spot for a voyage to South America, the researchers say. The journey would have taken less than two weeks, falling within the known range of Polynesian voyages around this time, says Matisoo-Smith. Other researchers have found indirect evidence that Polynesians might have made it to the Americas before Europeans. "But this is the first concrete evidence - not something based on a similarity in the styles of artefacts or a linguistic similarity," says Matisoo-Smith. It is also the first clear evidence that the chicken was introduced before the Europeans arrived. Genetic studies of modern South Americans have not uncovered any signs of Polynesian ancestry. But this is not surprising, says Matisoo-Smith. Ancient Polynesians were great explorers, but tended to settle only in uninhabited islands. It seems that if they found other people, they would usually turn around and go home, she says. Journal reference: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0703993104) |

|

O

Ojaitimo

Posted

posted

on

Wed, Oct 10, 2007 11:46 AM

This model of a Chumash canoe is on the parking structure on the corner of California and Santa Clara in Ventura.

|

Pages: 1 8 replies